Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Early Life as a Musician

I was born on March 6, 1844, in Tikhvin, Russia. Unlike other composers of my time, my family was not artistically inclined. Both of my parents played the piano. My mother was more accomplished than my father in that regard. All in all, we were a family that was focused entirely on our deeply rooted history and dynasty.

At six years old, I began taking piano lessons from the local teachers, but at that time, I had very little interest in playing seriously. I was more interested in stories: whether they be books, or the ones my brother, Voin, would tell me whenever he returned from his voyages with the navy.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Music Education & Military Career

Voin’s influence convinced me to abandon music at twelve years old and join the Imperial Russian Navy instead. Even so, during my studies at the Naval Academy in Saint Petersburg, I began taking piano lessons with a man named Ulikh. It was then that I began to appreciate music in all its intricacies. With the approval of Voin, who was director of the Naval Academy school at the time, I started taking lessons with Feodor Kanille in piano and composition.

Kanille introduced me to all kinds of new music, but it was the folksy tones that garnered my interest. Kanille also became a good friend to me. When Voin canceled my music lessons when I turned seventeen – he believed they served no “practical” purpose to me – Kanille continued to tutor me in private. Every Sunday, we would meet in his lodgings, and we would play duets together or discuss music. His tutelage broadened my view of the world.

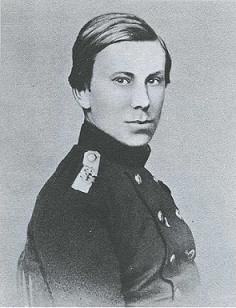

Image: Photo of a young Nikolai Rimsky-Korsako

Rimsky-Korsakov Helps Form The Mighty Handful

In November 1861, he introduced me to what would become “The Mighty Handful.” Finally, I found like-minded people in Mily Balakirev, Cesar Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Alexander Borodin. “With what delight I listened to real business discussions of unknown to me, formerly only heard of in the society of my dilettante friends. That was a truly strong impression.”

Becoming a part of The Mighty Handful created lifelong friendships between myself and the other composers, particularly with Modest Mussorgsky. He was a composer who did not compose conventionally. He had his own way with harmony and voice-leading. Mussorgsky’s music spoke directly to the soul. And his life was steeped in tragedy. Nevertheless, our friendship stretched many years beyond his death.

Alexander Borodin joined The Mighty Handful a year after I did. He was a chemist and a composer, but primarily a scientist who practiced music and composition during his downtime. I also devoted considerable time, effort, and dedication to championing his music by reworking it, orchestrating, and completing his unfinished works.

Swiftly, I found myself under Balakirev’s tutelage, and when I was not at sea, I was with him and The Mighty Handful. Balakirev taught me the basics of composition, the rules, so to speak, and it was then that I began composing my symphony in E-flat minor. Written entirely from my intuition, it would be a project that I would pick up and abandon whenever the feeling struck.

Shortly after I turned eighteen in 1862, I left on a two-year voyage. I thought that two years on a ship, the Almaz, would give me ample opportunity to hone my skill and maybe finish the symphony in E-flat minor. There was a piano, and Balakirev had loaned me some books on music and composition. Still, after a while, I found myself drifting towards literature — Homer, Shakespeare.

During the voyage, I mostly put aside my symphony. With no inspiration, “Thoughts of becoming a musician and composer gradually left me altogether… distant lands began to allure me, somehow, although, properly speaking, naval service never pleased me much and hardly suited my character at all.”

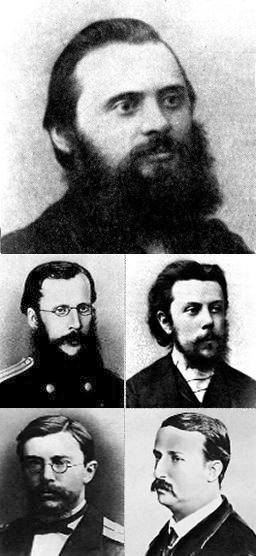

Image: Photos of composer, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mily Balakirev, Cesar Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Alexander Borodin

The Wise Teachings of Mily Balakirev Shape Rimsky-Korsakov’s Musical Education

Upon my return to Saint Petersburg in May 1865, I thought inspiration would strike me at once. Alas, the desire to compose was still missing. I had kept in contact with Balakirev during my voyage, and in September of 1865, I began to finally add more to my previously abandoned symphony in E-flat minor.

Balakirev had also convinced me to appear at what would be my first ever performance. A Russian orchestra performed my re-orchestrated symphony on December 31, 1865, to resounding success. Its second performance in March of 1866 solidified the idea that I was on the right track with my music.

At twenty-one, I appeared on stage in my naval uniform to receive the applause, shocking the crowd. A naval officer had composed this piece? Unheard of! It was Balakirev who conducted those performances.

Balakirev and I would eventually separate – I had begun to find him stifling – but his teachings shaped my early career. “A pupil like myself had to submit to Balakirev a proposed composition in its embryo, say, even the first four or eight bars! Balakirev would immediately make corrections, indicating how to recast such an embryo; he would criticize it, would praise and extol the first two bars but would censure the next two, ridicule them, and try hard to make the author disgusted with them. The vivacity of compositions and fertility were not at all in favor, frequent recasting was demanded, and the composition was extended over a long period of time under the cold control of self-criticism.”

At the age of twenty-one, I completed Overture on Three Russian Themes and Fantasia on Serbian Themes and the initial versions of Sadko and Antar.

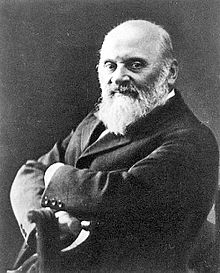

Image: Photo of Mily Balakirev

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Tone Poem and later Opera, Sadko

Sadko, inspired by the epic poem, saw extensive revisions and finally premiered on January 7, 1898, to great acclaim. It tells the story of Sadko, who leaves his wife to travel the world. Eventually, he would meet and marry the Sea-Kings daughter, and he would amass great riches before returning home.

I spent years revising it and followed the rehearsals very closely. When it premiered, it was to great acclaim. Promoters revived Sadko multiple times after my death.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Symphony Antar

Modest Mussorgsky told me the story that would inspire Antar. Antar saves a gazelle from a bird of prey and, exhausted by the efforts, falls asleep in the desert. Antar dreams of a palace where the Queen of Palmyre lives, and the queen reveals herself to be the gazelle he had saved.

She gifts him vengeance, power, and love, and he accepts, requesting that she kills him if the gifts become troublesome. I kept the legend in the symphony; each movement symbolizing a particular moment in the story.

Just like with Sadko, Antar would see extensive revisions. Upon its first publication, I had called it my Second Symphony, but later I would rename it to a symphonic suite. Berlioz influenced me to create Antar, especially after attending his performance of Symphonie fantastique.

In the years between my return to Saint Petersburg in 1865 and 1868, I spent more and more time in the company of The Mighty Handful. We talked, played music, debated nationalism, and created together. I orchestrated a march by Schubert in May 1868, when I was twenty-four, at the insistence from The Mighty Handful. I also orchestrated the opera, The Stone Guest, in honor of the very unwell Alexander Dargomyzhsky.

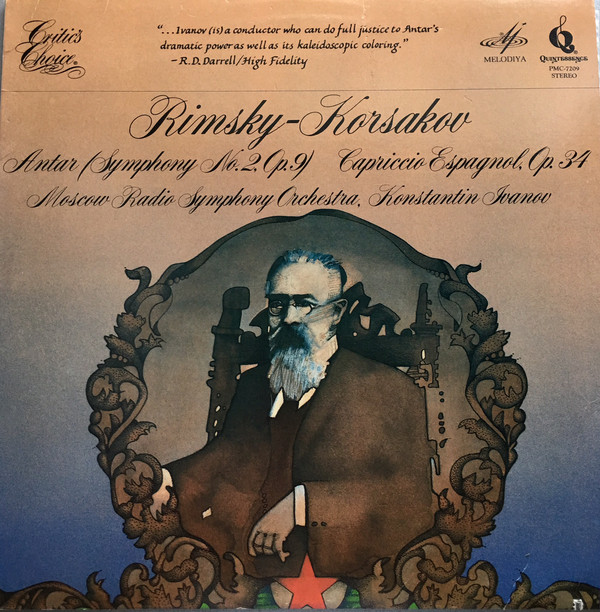

Image: Photo of the album cover Rimsky-Korsakov Symphonic Suite Antar

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Forms a Lifelong Friendship with Modest Mussorgsky

At twenty-seven, in 1871, Mussorgsky and I moved into Voin’s old apartment together. “That autumn and winter the two of us accomplished a good deal, with a constant exchange of ideas and plans. Mussorgsky composed and orchestrated the Polish act of Boris Godunov and the folk scene Near Kromy. I orchestrated and finished my Maid of Pskov.” We would share the day, Mussorgsky using the piano in the mornings and me in the afternoons. Our mutual talent inspired us both to carry on with our work.

The Maid of Pskov was the first opera I ever composed. Set during the times of Ivan the Terrible, it tells the story of Pskov’s people rebelling against his tyranny. I finished it in 1872, and a year later, it premiered in Saint Petersburg. I extensively revised The Maid of Pskov, eventually publishing the final version in 1892.

Image: Photo of Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, Russian composer

Rimsky-Korsakov Becomes a Conservatory Music Composition Teacher

The same year, I became the Professor of Practical Composition and Instrumentation at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. I still had no formal training or education in composition or music when I became the composition teacher at age 27.

I knew the rumors were flying when I received the position. Some said it was a political rebuttal against The Mighty Handful, and Balakirev, in particular, was always so very against academic music training and its stifling rules. There was no creative outlet.

Since I lacked the formal training or education I needed, I sought the advice of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whom I’d met through Balakirev. He advised me to study, and that is what I did. I became the conservatory’s “best pupil” and worked as hard as possible to give my students the most authentic experience while at the school.

Teaching also gave me the motivation to revise all of my previous work. Nothing was safe. I went back to the very first symphony (Symphony in E-flat Minor) and began the extensive job of revising everything. Learning at the conservatory had given me the skills I needed to become my best as a composer.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Marriage and Large Family

In December 1871, I became engaged to Nadzhda Purgold. We married a year later, in July 1871, and had seven children together. Our relationship was a professional one too, and she became my musical partner. Together, we would play and engage guests frequently.

At twenty-nine, the Imperial Navy made me Inspector of Naval Bands. I traveled all over Russia overseeing naval bands and naval students at different Conservatories.

With all my teaching and studying, I had begun to compose more classically, which brought backlash from my fellow nationalists, especially The Mighty Handful. My music was not well received by my peers. Afraid I would fall into another creative drought, I continued as best I could.

Image: Photo of Rimsky-Korsakov’s wife, Nadezhda Purgold

Rimsky-Korsakov Composes his Favorite Work: The Snow Maiden

It wasn’t until 1877, when I was thirty-three, that I began to loosen the shackles and began composing in earnest again, the way I wanted to. I wrote an opera based on the short story May Night by Nikolai Gogol, and finished it in November 1878. May Night broke me out of the rut, and I began working on The Snow Maiden.

The Snow Maiden would become my favorite work. Based on the play by Alexander Ostrovsky, I began composing it in 1880. It is four acts, with each one representing a different force of nature as mythological beings.

The Snow Maiden, daughter of Spring Beauty and Grandfather Frost, requests to live with the nearby village people, and it does not end well. It premiered in 1885 by the Russian Private Opera to great acclaim.

Although I was incredibly skeptical of all things magical and legendary, I found myself drawn repeatedly to composing music that was magical and legendary. “I doubt if you would find anyone in the entire world more skeptical of everything supernatural, fantastic, phantasmal, or otherworldly than I, and yet, as an artist, it is just these things that I love most. And ritual? What could be more intolerable than a ritual? I feel positively embarrassed, as though I were acting out a Commedia when I attend them, and this goes even for funerals. Yet with what delight I’ve depicted rituals in my music! No – I firmly believe that art is essentially the most fascinating and intoxicating of lies!”

Image: Photo of the album The Snow Maiden by Rimsky-Korsakov

Rimsky-Korsakov Joins Belyayev’s Artistic Circle

In 1882 in Moscow, I met Mitrofan Belyayev, who would later become the founder of ‘Belyayev’s circle.’ At the time, I had fallen into a creative rut. Mussorgsky’s passing had me set aside every project I had been working on, and I took his unfinished works into my own hands.

Belyayev was a patron of the arts, and he was intent on bringing their support to nationalist artists such as me. It was at one of his weekly soirees that I met Alexander Glazunov. After his First Symphony performance, I came up with the idea of having concerts featuring solely Russian composers and musicians.

Belyayev agreed to the idea, and it was there that the Russian Symphony Concerts were born. “By force of matters purely musical, I turned out to be the head of the Belyayev circle as the head Belyayev, too, considered me, consulting me about everything and referring everyone to me as chief.”

Belyayev’s circle was far different from The Mighty Handful. The Mighty Handful had more fixed ideas. In contrast, Belyayev’s Circle attempted to welcome a broad range of ideas, no matter how different they might be. We were progressive. Belyayev himself also invested time and effort into our talents. He set up the annual Glinka Prize and a small publishing firm that regularly published Alexander Glazunov’s music compositions as well as my works.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Attends Rimsky-Korsakov’s Russian Concerts & Influences Belyayev’s Circle

In November 1887, when I was forty-three, Pyotr Tchaikovsky came to visit me in Saint Petersburg. He attended a few of our Russian Symphony Concerts. Tchaikovsky was a fan of Belyayev and his accomplishments, and he enjoyed attending our gatherings. His attendance and advice influenced me and the other composers and musicians who participated in the Belyayev Circle meetings.

Our friendship evolved more and more with each visit. Tchaikovsky was popular, wildly successful, and famous, and his relationship with The Mighty Handful also became far friendlier than it had been.

Up until then, he had blamed Balakirev for my career, accusing him, in fact, of my lack of education. Although he did not always agree with Belyayev’s circle, his knowledge was valuable to us all.

That year, I had also decided to dedicate my creative outlet solely to operas. Inspired by Richard Wagner’s talent at conducting, I wanted to emulate how Wagner could bring music to life so vividly, even though I did not enjoy his music whatsoever.

“What terrible harm Wagner did by interspersing his pages of genius with harmonic and modulatory outrages to which both young and old are gradually becoming accustomed and which have procreated d’Indy and Richard Strauss.”

Image: Photo of Pyotr Tchaikovsky

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Famous Showpiece: Capriccio Espagnol

I composed Capriccio Espagnol shortly after Tchaikovsky’s visit. In 1887, at forty-three years old, I believed without a doubt that I had written my most intricate piece of music. With five movements and performed by an orchestra only, the entire work only takes sixteen minutes.

Although it was generally well-received, I became annoyed that audiences and critics overly focused on the piece’s orchestration. Their assumption that a composer could divorce orchestration from the composition of the music as a whole was wrong.

“The opinion formed by both critics and the public, that the Capriccio is a magnificently orchestrated piece — is wrong. The Capriccio is a brilliant composition for the orchestra. The change of timbres, the felicitous choice of melodic designs and figuration patterns, exactly suiting each kind of instrument, brief virtuoso cadenzas for instruments solo, the rhythm of the percussion instruments, etc., constitute here the very essence of the composition and not its garb or orchestration. The Spanish themes, of dance character, furnished me with rich material for putting in use multiform orchestral effects. All in all, the Capriccio is undoubtedly a purely external piece, but vividly brilliant for all that. It was a little less successful in its third section (Alborada, in B-flat major), where the brasses somewhat drown the melodic designs of the woodwinds; but this is very easy to remedy if the conductor will pay attention to it and moderate the indications of the shades of force in the brass instruments by replacing the fortissimo by a simple forte.”

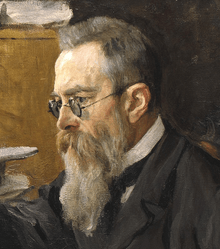

Image: Painting portrait of Rimsky-Korsakov

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Composes the Violin Showpiece Sheherezade

A year after Capriccio Espagnol, I took inspiration from the book, A Thousand and One Nights and began composing Sheherezade in the summer of 1888. After spending the winter working on Borodin’s Prince Igor, Sheherezade was the clean break I needed to start anew.

I did not want the four movements to be titled. “All I desired was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond a doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders and not merely four pieces played one after the other and composed on the basis of themes common to all the four movements.”

I conducted the premiere of Sheherezade in Saint Petersburg on October 28, 1888. Sheherezade became one of my most famous compositions. I later adapted the work for ballet.

Rimsky-Korsakov Suffers a Series of Tragic Events

A string of tragic events paused my career for a very long time. In 1892, at the age of forty-eight, I began suffering yet another creative drought, and my health took a turn for the worse. Dizziness, sickness, and shortness of breath led to a diagnosis of neurasthenia.

Shortly after, my mother and infant son died, and my wife and son became incredibly unwell. Although my wife would recover, my son would not. Depression descended like a curtain into my life. Composing became impossible, and I found no joy in music. I ended up quitting the Russian Symphony Concerts and retreating into myself.

After Tchaikovsky Dies, Rimsky-Korsakov Composes Again

It wasn’t until the death of Tchaikovsky that I began composing again. I started writing for the Imperial Theatres that Tchaikovsky had previously written for and composed an opera based on another of Nikolai Gogol’s short stories: Christmas Eve, Tchaikovsky’s opera. Vakula the Smith, was also based upon this story. I wrote both the libretto and the music for Christmas Eve. It was my way of honoring Tchaikovsky, his music, and his influence on me.

Image: Photo of the Opera, Christmas Eve by Rimsky-Korsakov

Rimsky-Korsakov Protects Saint Petersburg Conservatory Students During the 1905 Russian Revolution

In 1905, the Revolution began. It began a series of unchangeable events. I took it upon myself to provide the much-needed interference between students at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and the Russian authorities outside. By writing letters, I protected my students’ rights, eventually calling for the conservatory’s director’s resignation.

As the conflict progressed, the Saint Petersburg Conservatory expelled over 100 students, despite my efforts. Additionally, they dismissed me from my professorship. In utter defiance, I continued to teach privately as much as possible from the comfort of my own home.

My opera Kashchey the Deathless prompted a government protest that caused a ban on my works from being produced or shown in Russia.

Image: Photo of St. Petersburg Conservatory

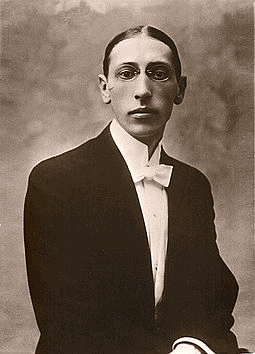

Private Tutoring of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Most Famous Student, Igor Stravinsky

During my time privately tutoring students, I met Igor Stravinsky. He was a good friend of my son, and I initially knew him as a frequent guest at our house. At that time, he exemplified the sad story of an artistic creative wanting to create.

Instead, his father pushed Igor into studying law. Despite his career as a famous bass singer, his father disapproved of his son taking up music as a vocation. After spending a summer in 1902 at my home, in the company of my family, Stravinsky became more and more convinced that he should compose rather than learn the law.

By 1905, I was teaching Stravinsky twice a week. His father had recently passed away, and Igor had begun to neglect his law studies in favor of music. Over time, I related to Igor Stravinsky as another son, and we remained close until I died in 1908. Stravinsky was exceptionally talented and would later become one of the most celebrated composers, pianist, and conductor of his time.

My teachings and music heavily influence his 1910 premiere of The Firebird. Relying heavily on Russian folklore, The Firebird was inspired by the poem A Winter’s Journey written by Yakov Polonsky. It’s easy to hear a touch of myself in Stravinsky’s ballet.

Image: Photo of a young Rimsky-Korsekov

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Life Ends from Ill-Health at Age 64

The St. Petersburg Conservatory reinstated me once Alexander Glazunov became director, but ill health forced me to retire in 1906 when my health took a turn for the worst.

I had been diagnosed with angina. I believe that the stress caused by the Revolution destroyed what little good health I had left. By December, I had become so unwell that I could no longer do my work as a composer and teacher.

I died in 1908, at the age of sixty-four, in my own home. I was buried in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg, next to some very dear friends.

Please find compelling quotes of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- The Pan Book of Great Composers by Gervase Hughes (Pan Piper, 1964)

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikolai_Rimsky-Korsakov

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nikolay-Rimsky-Korsakov

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/nikolai-rimsky-korsakov-433.php

- Tchaikovsky & Rimsky-Korsakov: http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Nikolay_Rimsky-Korsakov

- Tchaikovsky & the Belyayev Circle: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyotr_Ilyich_Tchaikovsky_and_the_Belyayev_circle

- Capriccio Espagnol: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capriccio_Espagnol

- Sheherezade: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scheherazade_(Rimsky-Korsakov)

- Igor Stravinsky: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igor_Stravinsky#Pupil_of_Rimsky-Korsakov_and_first_compositions,_1901%E2%80%931909