The Early Life of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

I was born on May 7, 1840, in Votkinsk, Russia, to a military family. My father worked as a mining engineer and served as a lieutenant colonel in the army. My mother leaned towards a career in the arts. She was French and German and had taught me the languages at a young age so that by six years old, I could speak them fluently.

Although historians and critics have speculated about my mother’s relationship with me, I was well looked after and doted on my father, mother, and our nanny. I was always inclined towards music (my fondest childhood memory is playing with an orchestrion). At five years old, I began taking piano lessons, and my parents were quite supportive of this nurturing talent I seemed to have.

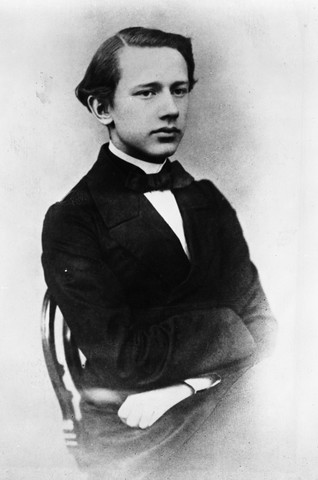

Image: Photo of a young Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Schooling for Future Work in Civil Service & Music

It was apparent they wanted more for me than a music career, though. At the time, becoming a musician or composer was not a viable career. There was very little financial support on the job and even less financial stability. From a young age, my parents pushed me towards a career as a civil servant.

In 1850, at ten years old, I was signed up to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg. Since I was too young to attend (entry age was twelve years old, and I was only ten), I attended a preparatory school beforehand, which I did not enjoy.

Coming from a doting family, straight into independence in a school with minimal comfort or human contact experience, was traumatizing. I was not emotionally prepared to separate from my mother and the nanny that had educated me. To further my pain, in 1854, while at school, my mother died of cholera. I was only fourteen at the time, and not knowing how else to express myself, I composed a waltz in her honor.

Father, who had also contracted cholera but recovered without much ado, sent me back to school, hoping that concentrating on my schoolwork would keep me occupied as a way to lessen my grief. It worked, to an extent.

I continued to study the required coursework to prepare me for a career in civil service. I also studied music composition and piano and attended operas performed in Saint Petersburg in the company of a few good friends I had made while at school.

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Career as a Civil Servant

A year after my mother’s passing, my father paid for private music lessons with Rudolph Kundinger and Gabriel Lomakin. I remained at the school until nineteen years old, after which I graduated and fulfilled my father’s wishes to pursue a stable career by taking a job as a clerk in the Ministry of Justice. For three years, I worked in the ministry, which I despised, and couldn’t help but feel the seismic pull of music.

After my post at the Ministry of Justice ended, I enrolled in the newly opened Saint Petersburg Conservatory. There, I dedicated my time studying counterpoint and harmony, determined to make something of myself. I also attended classes at the Russian Music Society to learn music theory at a more in-depth level.

Image: Photo of Saint Petersburg Conservatory in Russia

Beginning A Career in Music

Determination paid off. I graduated from the Conservatory in 1865 with a silver medal for my cantata and a finished composition of Characteristic Dances that was then performed by John Strauss II on September 11 1865. With music influenced by Europe and Russia alike, I found myself becoming quite popular.

A critic once wrote to me: “You are the greatest musical talent of contemporary Russia, more powerful and original than Balakirev, more creative than Serov, infinitely more cultivated than Rimsky-Korsakov. In you, I see the greatest, or rather, the only hope of our musical future.”

I took the praise modestly, but it became apparent that my talent was highly coveted. In 1866, at only twenty-six years old, I was appointed Professor of Harmony at the new Moscow Conservatory founded by Nicholas Rubinstein. The job gave me ample opportunity and time to compose at my leisure.

Pyotr Ilyich’s Tchaikovsky Composition: Winter Dreams

My composition, Winter Dreams, was indeed the result of having that time. The work contained a piece of my heart, and I often thought about it. I wrote this to my patroness in 1883: “…although it is in many ways very immature, yet fundamentally it has more substance and is better than any of my other more mature works.”

Image: Photo of the album cover, Winter Dreams by composer, Tchaikovsky

Peter Tchaikovsky Meets Balakirev, Composes Romeo and Juliet & Undine

In January 1868, I met Balakirev while he was on a trip to Moscow. Balakirev was immediately interested in what I had to offer and proposed we work together on Romeo and Juliet as a symphonic fantasy. Under his careful guidance, Romeo and Juliet became the catalyst to my career.

Based on the famous Shakespeare play, Romeo and Juliet, my symphonic poem, which closely follows the original story. When taking on the Romeo and Juliet project, I had been struggling to finish Undine.

Undine would never come to be; instead, the composition joined the small pile of other unfinished works I ended up destroying. I had warned Balakirev I felt close to my breaking point, but he would not take no as an answer.

The first premier of Romeo and Juliet was not all that successful. A court case against Balakirev, unfortunately, overshadowed its premier. My second version in 1872 was much better. It wasn’t until 1880, though, that it reached success after more revisions, including a wholly revised ending.

Image: Photo of the album cover Romeo and Juliet, by composer Peter Tchaikovsky

Tchaikovsky’s Love Affair with Belgian Singer, Desiree Artot

Romeo and Juliet would never have become the piece it became, though, if it hadn’t been for a tempestuous love affair with the Belgian singer Desiree Artot. Falling in love for the first time, so quickly and hard, prompted my creativity to leap. It wrote to a friend: “The creative process is like music which takes root with extraordinary force and rapidity.” And I wrote to another friend: “I love her with all my heart and soul, and I feel I cannot live without her.”

But to live without her, I had to. Although we were engaged to be married, neither Desiree nor I was willing to compromise on wholeheartedly pursuing our careers and settling down. She left me, later marrying a singer. The split stung, and I found myself seeking solitude more often than not.

Image: Photo of singer, Desiree Artot

Peter Tchaikovsky Meets the Five Mighty Handful of Russian Composers

After Romeo and Juliet’s success, I met the Five, otherwise known as The Mighty Handful, consisting of César Cui, Aleksandr Borodin, Mily Balakirev, and Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. They were a group of composers who pushed the boundaries of composition by focusing on Russian music rather than Western European origination.

I was adamant; I would work independently of other composers and transcend the limitations they had set for themselves. My goal was to create music that would appeal to the more steadfast Russian minds and people of a more unconventional mindset.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: A Gay Man in 19th Century Russia

My sexuality and gay relationships caused chatter while I was alive, and more so after I died. Although I was never open about my sexuality, being a gay man in Russia in the mid-1800s was very difficult. To this day, the Russian government has censored journal entries that could have confirmed my sexuality. It is impossible to find passages in my writings that specify my romantic and sexual relationships, other than to Desiree Artot.

Fortunately for me, homosexuality was mostly ignored by upper-class society at the time, and I was able to lead my romantic and sexual life due to people deliberately cutting me the slack afforded to celebrities.

After my jilted romance with Desiree, I had no interest in pursuing heterosexual romance, but while teaching at the Moscow Conservatory in 1877, I met my future wife, Antonina. At the time, I wanted to avoid bringing shame to my family for so openly being myself. So I chose the more comfortable option of finding a wife and attempting to settle down and even having a family.

Image: Photo of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky sitting in a chair

Peter IlyichTchaikovsky’s Questionable Marriage to Antonina Miliukova

Antonina was a music student who was indubitably obsessed with me. “Some mysterious power drew me to the girl… One evening I went to her, told her frankly that I could not love her, but that I would be her faithful and grateful friend. I described my character in detail, my irritability, the unevenness of my temperament, my misanthropy, and my material condition. Then I asked her to marry me. The reply was, of course, in the affirmative.” We married on July 18, 1877. I was thirty-seven years old.

But it was to be yet another disastrous relationship. The conflicts I had with my sexuality, and the unwillingness to give Antonina something I had strictly denied her from the start, caused my mental health to spiral.

Soon after our wedding, only two and a half months to be exact, I was faced with a nervous breakdown that propelled me to attempt taking my own life by drowning myself in an ice-cold river. Instead, I contracted pneumonia from which I recovered, but my relationship and marriage did not survive.

I fled to my brother Modest’s home to recover from the ordeal. I had written to him before my suicide attempt, explaining that I couldn’t be in this marriage any longer. “I have taken no advantage of her, for I warned her from the outset to expect no more than brotherly affection. Physically, she revolts me.”

I was quite happy at Modest’s home and found myself enjoying the small simplicities of life, like the growing of flowers. “When I am old and past composing, I shall spend the whole of my time growing them.”

The pain I felt in those times can be heard quite plainly in my works. Being gay in an unaccepting country during an unaccepting time was difficult. It affected my mental health quite a lot, and I was consistently at war with myself.

Image: Photo of Tchaikovsky and his wife, Antonina

Tchaikovsky’s Patronage and Remote Friendship with Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck

After my marriage ended, I became acquainted with Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck. She was an extremely wealthy widower from Russia who became a large investor in the performing arts after her husband’s sudden unexpected death. Usually, she could be found at her home, as far from society as one could get, except for the nights she attended concerts by the Russian Music Society in Moscow.

She was well known by Rubinstein and Claude Debussy as they had either worked for her or befriended her. One day, a former student of mine recommended me as someone who may help her as she was looking for someone to commission a few music pieces. My former student told me that Nadezhda had already heard of me.

The Tempest, a symphonic poem I had composed in 1873, was one of her favorites of mine. After quizzing Rubinstein on my availability, she wrote me several letters, commissioning pieces that ranged from songs to a funeral march.

From those letters, it became apparent that we were well suited for each other. Nadezhda’s strict stipulation that we never meet under any circumstances propelled a long and fruitful friendship. Over thirteen years, her patronage meant that I could concentrate on composing full-time; I was never without work.

Image: Photo of Tchaikovsky’s friend, Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck

“It is absolutely necessary for a composer to shake off all the cares of daily existence, at least for a time, and give himself up entirely to his art life.” I eventually left my job at the Moscow Conservatory as a steady stream of commissions from her allowed me the luxury of having a career through creating new music.

She wrote to me once: “I want you to speak to me, and to no one else, of nature and destiny, of heartbreak, trampled faith, wounded pride, of happiness irretrievably lost, of self-abandonment to despair. No art can express all this as music can, and no one understands me better than you do.”

Our relationship was passionate, at a distance. It kept me fed and inspired, and I was personally fond of Nadezhda and grateful for her financial support. She suddenly and inexplicably ended her patronage and our friendship. I was not able to discover her reasons for doing so.

Tchaikovsky’s Opera: Eugene Onegin

Thanks to Nadezhda von Meck’s influence, one of the operas that I created was Eugene Onegin. Inspired by Alexander Pushkin’s novel of the same name, it tells the story of a young man’s journey from rejecting a woman’s love to dueling his best friend to death.

Although I was not fond of the original novel’s plot, I concentrated on exploring the character development and its effect on the story during composition. It premiered in March 1879 under the direction of conductor Nicholas Rubinstein.

Peter Tchaikovsky Composes his Famous 1812 Overture

Based on the historical battle of 1812, where Napoleon’s army met Russia’s under General Michael Kutuzov, I composed the 1812 Overture under Rubinstein’s suggestion. It took six weeks from start to finish. After the assassination of Alexander II, concert organizers canceled the commemorative celebration and premiere of the piece.

Instead, the orchestra performed the 1812 Overture in 1882 within a tent near the unfinished cathedral, which did not make me very happy. “[I] was not a conductor of festival pieces… [the Overture] would be very loud and noisy, but without artistic merit, because I wrote it without warmth and without loved.” It was ironic, I suppose, that the Overture would be the piece that would make me most famous within my lifetime.

Image: Photo of the album cover to composer, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture

Peter IlyichTchaikovsky and The Belyayev Circle

After a spate of traveling, I returned to Saint Petersburg in November 1887, attended a number of the Russian Symphony Concerts, one of which even performed my First Symphony and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Third Symphony.

I had become friends with some of the Mighty Five over the years, and Rimsky-Korsakov was a composer I easily kept in touch with, defying my usual need for solitude. Once, I wrote a review for Rimsky-Korsakov’s Fantasy on Serbian Themes, saying:

“Its charming orchestration… its structural novelty, and most of all … the freshness of its purely Russian harmonic turns… immediately showing Mr. Rimsky-Korsakov to be a remarkable symphonic talent.”

During my visit to Saint Petersburg, I discovered several of the Five had moved on from their original Mighty Five circle to create another composers’ group: the Belyayev Circle. I became well acquainted with the Belyayev Circle men. I found it was easy to speak with them — unlike with the Five, the relationship of which was always fraught and negatively felt, not to mention the barrage of negative reviews I consistently received from composer César Cui.

My visit came on the back of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s speech about universal unity, and with it, the popularity of my music soared. A cult following for my music and me as a composer ensued.

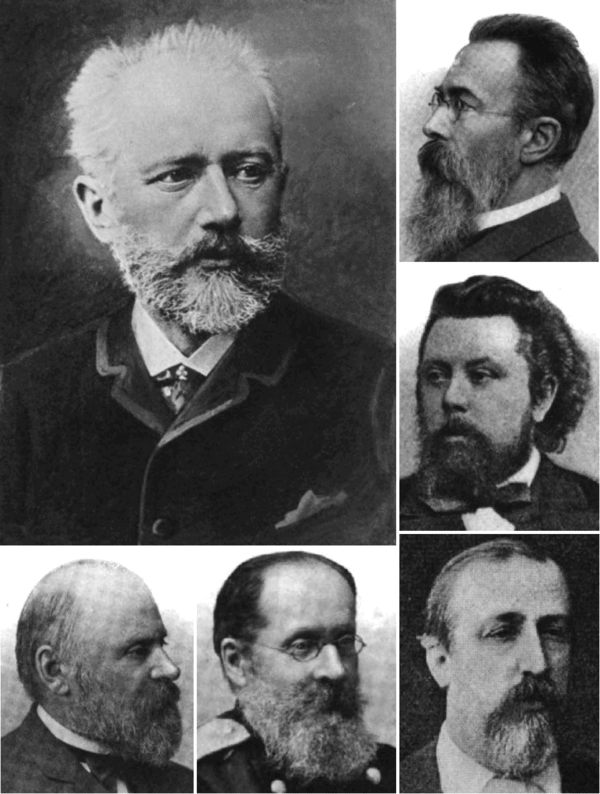

Image: Photo of Tchaikovsky as well as other composer’s in the Belyayev Circle

Tchaikovsky Pursues Conducting to Promote his Orchestral Works & Earn Needed Income

In 1887, I also conducted a performance for the first time. For years, I had convinced myself that I was not a conductor but a composer, yet after a successful night, I found that I enjoyed it far too much to give it up.

In 1890, I received a letter from Nadezhda informing me that she was cutting contact and cutting funds. I had become quite enamored with our friendship and depended on our consistent communication with each other. The sudden ending of the relationship threw me into a deep depression. “My faith in my fellow humans and my confidence in the world itself are undermined. I have lost my tranquillity, and the happiness that fate might yet have held in store for me is gone forever.”

Thus, I began traveling again, appearing as a guest conductor all over Europe. In 1891 I traveled to America for my debut performance at the Carnegie Hall in New York.

But in 1890, I received a letter from Nadezhda informing me that she was cutting contact and cutting funds. I had become quite enamored with our friendship and depended on the constant communication that the quick ending of the relationship threw me into a deep depression. “My faith in my fellow humans and my confidence in the world itself are undermined. I have lost my tranquillity, and the happiness that fate might yet have held in store for me is gone forever.”

Peter Tchaikovsky’s Very Successful Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty & Nutcracker Ballets

Most likely, I am most famous and widely recognized in your time for my ballets — most notably: The Nutcracker, Sleeping Beauty, and Swan Lake. I was not a fan of ballets. I found them repetitive and boring, with not much nuance.

It was not until I studied a few that I realized I was mistaken. “I listened to the Delibes ballet Sylvia… what charm, what elegance, what wealth of melody, rhythm, and harmony. I was ashamed, for if I had known this music then, I would not have written Swan Lake.”

I was commissioned to compose Swan Lake in 1875 by Vladimir Petrovich Begichev, the Imperial Russian Theatre director. It tells the story, inspired by both German and Russian folklore, of Odette, a princess cursed by a sorcerer to become a swan until true love breaks the curse.

Swan Lake was not successful during its first premiere on January 15, 1895, but is now one of my most famous pieces. After extensive revisions, it was performed at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg in 1895, after my passing, to resounding success.

Image: Photo of the album by Tchaikovsky, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty & Nutcracker Ballets

The second ballet I composed was Sleeping Beauty. The director of Imperial Theatres in 1888 asked me to adapt a ballet from the story of Undine. I accepted right away, hoping that this new venture would bring more enthusiasm after the lackluster reception of Swan Lake.

I based Sleeping Beauty on the Brothers Grimm retelling of the original folktale after immersing myself in the story, reading both the original and the Brothers Grimm’s account. The commission included a list of rules to abide by and began work right away. It took less than a year from composition to orchestration.

Unfortunately, I passed away before ever witnessing Sleeping Beauty’s premiere, but it was far more successful than Swan Lake, with it being performed over one hundred times in the space of ten years.

The Nutcracker was the last ballet I composed. Once again, I was commissioned by Ivan Vsevolozhsky of the Imperial Theatres in Saint Petersburg to create a piece that was both an opera and a ballet. Based on E. T. A Hoffman’s story, The Nutcracker tells the story of a prince turned nutcracker having to fight the Mouse King to return to his natural human form.

Unfortunately, the very first performance was not a success. Critics lambasted the dancers and the choreography saying: “One can not understand anything. Disorderly pushing about from corner to corner and running backward and forwards— quite amateurish.”

However, my music received some praise, with some critics saying it was “astonishingly rich in detailed inspiration” as well as “beautiful, melodious, original and characteristic.” The Nutcracker gained popularity in England after my passing in 1934, sporting regular annual performances after that. It is a Christmas tradition in America, with ballet companies often accounting for almost half of their yearly revenue.

Tchaikovsky’s Symphonies and Other Instrumental Works

One could say I struggled with writing major instrumental works. I composed six symphonies and was comfortable in the symphonic genre. I did not strictly follow symphonic form, and thus there was a lot of criticism surrounding my work and the way I composed music.

“Brahms stayed an extra day to hear my Fifth Symphony and was very kind… I like his honesty and open-mindedness. Neither he nor the players liked the finale, which I also think rather horrible.”

Although my earlier work may not be as widely recognized today, my last three symphonies receive more performances in your day. Ranging from symphonic poems to Manfred, I made a name for my work. Francis Maes, a music critic, described my symphonic works as “profound in emotional and psychological import” and “most romantic work. No other work is close to Berlioz, Liszt, and — in sonority — Wagner.”

The one thing I was never able to accomplish was finishing an opera successfully, even after writing eight of them. “What I need is to believe in myself again— for my faith has been greatly undermined’ it seems to me my role is over.” It was far from over, though.

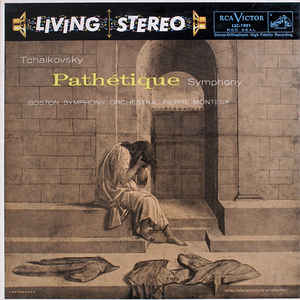

Tchaikovsky’s Symphonie Pathetique, Ill-Health & Death

During the dark period of my life, after the letter I received from Nadezhda, I composed Symphonie Pathetique. I poured every moment of hostility, sadness, and morbidity into the piece. “I have put my whole soul into this work… you cannot imagine what joy I feel at the thought that my days are not yet over and that I may still accomplish much.”

Unfortunately, after its lackluster premiere on October 28, 1893, I drank a glass of unboiled tap water and succumbed to cholera.

My brother, Modest, recalled, “Pyotr Ilych opened his eyes. There was an indescribable expression of unclouded consciousness. Passing over the others standing in the room he looked at the three nearest him, and then toward heaven. There was a certain light for a moment in his eyes which was soon extinguished, at the same time with his breath. It was about three o’clock in the morning.”

I died on November 6, 1893. Although I died an untimely death, my legacy has lived past me, my music becoming a part of culture worldwide.

Image: Photo of the album cover of Tchaikovsky’s Symphonie Pathetique

Please find compelling quotes of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- Great Composers 1300-1900 by David Ewen

- Great Composers by Gervase Hughes

- The Lives of Great Composers by Harold C. Schoenberg

- Pyotr Tchaikovsky: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyotr_Ilyich_Tchaikovsky

- The Five: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyotr_Ilyich_Tchaikovsky_and_The_Five#Belyayev_circle

- Tchaikovsky: https://biography.yourdictionary.com/peter-ilyich-tchaikovsky