The Early Life of the Prodigy, Franz Liszt

After the Pressburg concert, aristocrats, amazed by my talent, offered to sponsor my education in Vienna. I was nine years old at the time and already creating a fan base that would follow me for the rest of my life.

I debuted in Vienna on December 1, 1822. The concert took place at Landstandischer Saal to great success. At the time, I was studying under the tutelage of Carl Czerny for piano (he had been a student of Ludwig van Beethoven) and composition with Antonio Salieri. The latter was the director of the Viennese court. There are stories of Beethoven attending one of my concerts and kissing me on the forehead.

My father had taken leave of absence from his appointment with the prince to take me to Vienna, and in 1823 he requested a further two years when I began a small stint of touring. I performed for George IV at Windsor Castle before premiering Don Sanche in Paris in 1825.

In 1823, at only twelve years old, my composition was published a music anthology called Vaterländische Künstlerverein published one of my pieces. The collection was a bind-up of musical variations by great composers, including several waltzes by Beethoven himself. I was the only child composer published in this anthology.

That same year, I attempted to enter the Paris Conservatory to further my studies. Although my exam went well, Cherubini denied my entry because I was not French, and he did not like the route I was taking with my music. Instead, I began studying theory and composition with Antoine Reicha and Ferdinando Paer, respectively.

Franz Liszt Loses His Father & His First Girlfriend. Liszt Turns to Religion for Solace

My tour ended in 1827 after my father contracted typhoid fever. He passed very quickly, and his unexpected death was traumatizing to me. I turned to religion and reunited with my mother in Paris. To make ends meet, I sold my grand piano and began teaching piano for a stable income.

It was while teaching that I met Caroline de Saint-Cricq. We were young, she was only seventeen when we fell in love, but her father would not let us be together. He banished me from his estate and married Caroline off to a wealthy landowner.

Heartbroken, I disappeared. Turning once again to religion, I isolated myself inside a church, recusing myself so thoroughly that people believed I had passed away. Local newspapers printed obituaries, concluding that I had died.

Image: Drawing of Adam Liszt, Franz’s father

It wasn’t until the July Revolution in Paris that I rejoined society. War inspired my Revolutionary Symphony, which later became the Symphonic Poem Heroide funébre. My mother said, “The guns cured him,” and it was true. I found myself frantically beginning the Revolutionary Symphony, even though it would remain unfinished until Heroide funébre.

It would not be the last time, though, that I turned to religion during difficult moments in my life. I had found religion’s daily monotones to be calming and even inspiring at various points in my life after a bizarre twist of fate.

“Supreme serenity still remains the Ideal of great Art. The shapes and transitory forms of life are but stages toward this Ideal, which Christ’s religion illuminates with His divine light.”

Liszt Befriends Berlioz, Chopin, Wagner & Paganini

There was one thing I never went without, and that was friendship. I was close with some of the most inspiring artists of my time, from Victor Hugo to Richard Wagner. Wagner and I would later fall out when my daughter Cosima abandoned her husband to be with Wagner, and it caused friction in my relationship with Cosima more so than with Richard.

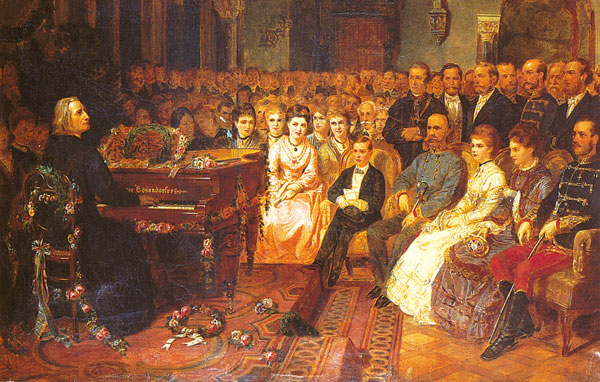

Image: Painting of Franz Liszt playing piano while friends including composer, Paganini watch

There was one thing I never went without, and that was friendship. I was close with some of the most inspiring artists of my time, from Victor Hugo to Richard Wagner. Wagner and I would later fall out when my daughter Cosima abandoned her husband to be with Wagner, and it caused friction in my relationship with Cosima more so than with Richard.

However, I made friends quickly, and in 1833, when I was twenty-two, I supported Berlioz, who was in financial ruin by that point, by publishing a transcription of his Symphonie fantastique. He was struggling to gain traction with it and was hemorrhaging money. The transcript helped him make back some of what he lost.

Although both Wagner and Berlioz were older than me, I found myself drawn to them quite magnetically. They were talented composers and musicians, but the person that most influenced my career was Chopin.

We met in 1832 during his recital. We admired each other, and Chopin “revealed a new phase of poetic sentiment combined with such happy innovations in the form of his art.” Our friendship lasted a good nine years, and it wasn’t until our significant others came at war with each other that it ended, as most relationships do, by drifting apart.

Another musician whom I admired greatly was Paganini. I met him in 1831 during his debut in Paris. He was an incredible violinist, and I had decided I wanted to be him, but on the piano. I composed 24 Études d’Execution Transcendante d’aprés Paganini, published in the early 1850’s, based on his violin works.

Chopin’s work and art greatly influenced me throughout my life. “The greatness of this genius, unequaled, unsurpassed, precludes even the idea of a successor. No one will be able to follow in his footsteps; no name will equal in his glory.”

Liszt’s Affair & Marriage to Countess Marie d’Agoult

In the same year, 1833, I began a relationship with Countess Marie d’Agoult, and also became friends with Felicité de Lamennais, who was a Catholic priest and remained a close tie relation between myself and the church.

Marie became a huge inspiration. We met in the winter of 1832 and 1833 when I was twenty-one. She was estranged from her husband and repeatedly sent me invitations to her salons that I periodically rejected. When I finally accepted one of them, we quickly became involved, exchanging numerous romantic letters. She was creative and artistic herself, a writer who would later publish under the pen name Daniel Stern; she ghostwrote for me on occasion.

We separated shortly after the affair as I went on tour again. In 1835, Marie lost her daughter, Louise, and she descended into a deep depression. We reunited a few months after, and she fell pregnant.

Image: Portrait painting of Marie d’Agoult

Much to my priest friend Lamennais’ horror, we decided to elope. He begged me on his knees to reconsider, telling me that I was making a monumental mistake.

Marie officially left her husband by letter, saying, “Your name will never leave my lips except pronounced with the respect and esteem that are due to your character; as for me, as concerns the world which will cover me with scorn, I ask of you only silence.”

Our marriage lasted until 1839 when I was twenty-eight. We had three children together. From my perspective, the marriage amicably ended before I left to tour Europe for eight years.

Liszt’s Eight-Year “Lisztomania” Tour

During my tour, I received honors and wrote Three Concert Etudes. I even received an honorary doctorate from the University of Königsberg.

It was during this time that ‘Lisztomania’ came to be. I had always been a handsome man and, as previously mentioned, had a large fanbase. It was common for women to throw their jewelry at me and for attendees to race for my gloves, which I often left on pianos at the end of concerts.

Image: Painting of Franz Liszt performing a concert on piano

Sometimes, women even went for my cigar stubs, which they found backstage. One historian has reported: “Liszt once threw away an old cigar stump in the street under the watchful eyes of an infatuated lady-in-waiting, who reverently picked the offensive weed out of the gutter, had it encased in a locket and surrounded with the monogram ‘F/L.’ in diamonds, and went about her courtly duties unaware of the sickly odor it gave forth.” Unimaginable!

Wherever I went, it was not long before word spread. After I arrived in Berlin in 1841, thirty students serenaded me with a rendition of Rheinweinlied.

Franz Liszt’s Romance with Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein Who He Could Not Marry

In 1847, at thirty-six years of age, I toured Vienna, Prague, Pest, Transylvania, Bucharest, Moldavia, and Kyiv. It was during this time that I met the illustrious Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein. She challenged me intellectually and artistically, and it was not long before we fell in love.

The following year, Carolyne and I reunited at Schloss Gratz, and I moved into her lodgings. We would hold salons meant to stimulate artistic minds as well as our own.

Unfortunately, my stay in Weimar was far from easy. There was much political unrest and civil war, and the public was not overly interested in concerts. Money was in short supply. My orchestra was restless; their moods were very low.

Images: Drawing of Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein with her daughter

I wrote a letter to a virtuoso who had asked to join us: “Unfortunately that is the case here too, although our dear Weimar continuing free, not only from the real cholera, but also from the slighter, but somewhat disagreeable, periodical political cholerina, may peacefully dream by its elm… should circumstances and conditions, however, turn out as I wish, then the Weimar band would consider it an honor and a pleasure to possess you, my dear sir, as soon as possible as one of its members.”

Carolyne eventually convinced me to stop giving concerts and instead concentrate on conducting and composing. I gave my last performance in Elisavetgrad.

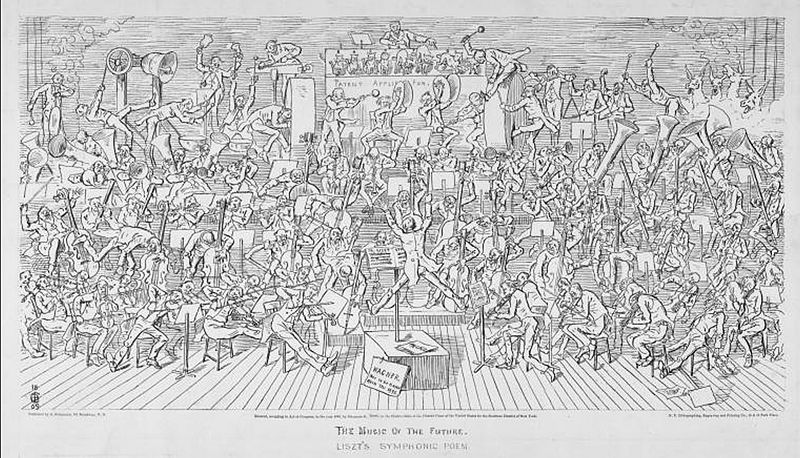

Franz Liszt Invents the the Symphonic Poem

In 1848, I also concentrated my efforts on what would later become the symphonic poem. It was a type of musical piece that would illustrate poetry, painting, or a different kind of artistic work, such as a story. The symphonic poem became my most notable achievement.

Image: Drawing of the Symphonic Poem by Liszt

I took up a position with Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna of Russia and settled in Weimar once again. I played for her, but her growing deafness, especially in her later years, meant she could not enjoy the music as thoroughly as she once did.

Princess Carolyne lived with me by that time, and it was then that we tried to marry but were unsuccessful in proving her previous marriage invalid.

At first, she successfully received an annulment in 1860 from the Vatican, but when we attempted to marry in Rome on October 22, we were stopped by the Vatican again. The disappointment of not being able to wed Carolyne came just after the death of my son, Daniel. He died of tuberculosis. I once again descended into depression. Little did I know that I would also lose my daughter in who died while giving childbirth a year later.

Franz Liszt Loses Children, Turns Again to Religion, Takes Holy Orders & is Known as ‘Abbe Liszt’

It all became too much, after. I desperately sought the peace and solitude that the church had given me when I was a heartbroken, devastated teenager. I retired to a monastery outside Rome and took my holy orders. Although I was not allowed to become a priest as I wanted, I was tonsured and became known as ‘abbe Liszt’.

I continued to compose and conduct when needed. I finished my oratorio Christus while living at the Vatican. I left only once to stop Wagner and my daughter Cosima from continuing their romantic union. But my campaign was unsuccessful.

Instead of continuing to live in Rome, I decided to return to Weimar. Several years later, I received the honorary title of Royal Hungarian Counsellor to Emperor Franz Joseph.

Franz Liszt’s Later Years as a Teacher, Composer & Philanthropist

My musical activities had significantly slowed in my later years. In 1873, and with associates’ help, I formed the Franz Liszt Foundation to honor my fiftieth anniversary.

It was a foundation to help struggling students. For a few years, the foundation was successful enough that no student lacking financial means had to pay for their musical education.

In March of 1875, at age 64, I received an honor by being nominated to the president of the newly approved Royal Academy of Music in Budapest.

I died on July 31, 1886, when I was seventy-five, from pneumonia. I took a fall down a long series of stairs at a hotel in 1881 and was severely injured, requiring complete immobilization for eight weeks. I never fully recovered.

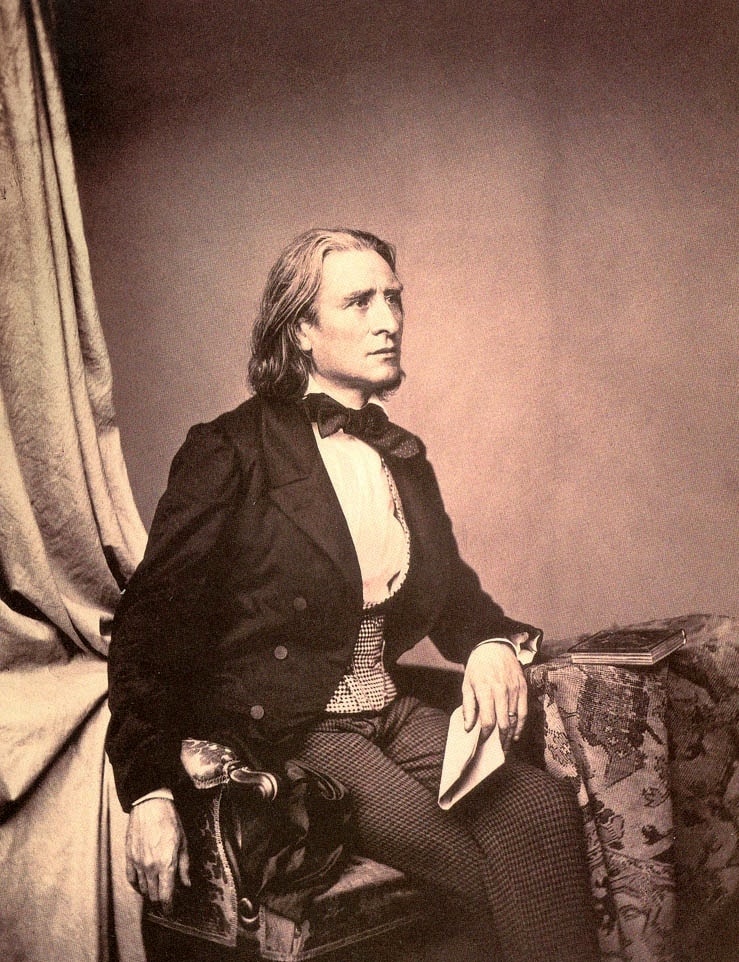

Image: Photograph of composer Franz Liszt

Not only did I begin attracting other physical ailments, but I again found myself stuck in a deep depression. “I carry a deep sadness of the heart, which must now and then break into sound.” Although I still composed, it was not with the same fervor and dedication as before.

When pneumonia struck, it was during a performance of Tristan and Isolde at the Bayreuth Festival. I had attended because my daughter Cosima was hosting. I hoped to rekindle my lost friendship with Richard Wagner during the festival. Instead, I passed before I was able to reconcile with Wagner.

I was buried in a cemetery in Bayreuth on August 3, 1886, against my wishes.

Please find compelling quotes of Franz Liszt here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- Franz Liszt: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Liszt#:~:text=Franz%20Liszt%20(German%3A%20%5B%CB%88l%C9%AAst,greatest%20pianists%20of%20all%20time.

- Biography: Franz Liszt: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Franz-Liszt

- Liszt’s Chronology: http://lisztomania.wikidot.com/liszt-s-chronology#toc1

- The Death of Adam Liszt: http://lisztomania.wikidot.com/the-death-of-adam-liszt#:~:text=Within%20days%2C%20however%2C%20Adam%20had,the%20church%20of%20St%20Nicolas.

- Adam Liszt: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Liszt

- Lisztomania: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisztomania

- Franz Liszt Facts: https://www.francemusique.fr/en/franz-liszt-10-little-things-you-might-not-know-about-composer-20447

- Great Composers by Gervase Hughes (Pan Piper 1964)

- Great Composers by David Ewen (The H. W. Wilson Company New York, 1966)