César Franck Pushed To Perform on Piano from His Childhood

Did I work myself to death? Perhaps so. Since my childhood, I used my talents as a pianist and composer to line my parents’ pockets, ensuring financial stability in financially hard times.

Like Beethoven, my father pushed my violinist brother to study music to generate revenue by playing violin and piano concerts throughout our years of growing up and studying music.

Often, the stress and pressures of forced performance took their toll on me. Perhaps that is why my later years, quietly composing, teaching, and serving as a church organist, are so starkly different from my early years.

I was born in Liege on December 10, 1822, to an otherwise typical family. My father was a bank clerk, and my mother stayed at home to look after my brother and me. Since a young age, I possessed an innate talent for art and music, continually leaning towards drawing and the piano. My father, spotting this, saw a future for me as a young child prodigy of the piano.

Image: Photo of a young César Franck

César Franck’s Youthful Training at The Liege and Paris Conservatories

My father entered me in the Royal Conservatory of Liege in 1831 at only age eight, and shortly after that, my father took my violinist brother and me on a tour where I played my first concerts in 1834. A year later, my father sent me to Paris to study under Anton Reicha and Pierre Zimmerman to prepare to enter the Paris Conservatory.

During that time, the Paris Conservatory required French citizenship to attend. The Paris Conservatory rejected my brother and me. Born in a part of France that was part of Belgium, my father applied for French citizenship. The government eventually approved him for naturalization, which then extended to my brother and me. Little did I know that I would only legally be a French citizen until I reached twenty-one years old. It would later become a problem.

Within a year of attending the Paris Conservatory, I won a Grand Prix d’Honneur, a first prize award for fugue, and an additional prize for organ performance. I was eligible to enter the Prix de Rome, but my father was determinedly against the idea. He wanted a performance career for me, and as far as he was concerned, it had to begin immediately. He didn’t want me to waste time traveling for free when I could be earning good money.

The Organ Becomes César Franck’s Primary Musical Instrument Reflecting His Growing Discomfort with Seeking Fame

I retired from the Conservatory on April 22, 1842, and began performing in concerts more regularly. It was during this time that I fell in love with the organ. At first, in concert, I would perform showy pieces that leaned more towards the operatic, but my compositions became more serious when I began playing the organ.

We returned to Belgium in 1842, and my father had grand ideas of money flowing like a river towards us, but unfortunately, it was not so. There was not much work to be had for two young musicians such as myself on piano and my brother on violin, and so, defeated, we returned to Belgium less than two years later.

In that time, I composed a set of trios for piano, violin, and cello, hoping to impress Franz Liszt. Later, Liszt wrote to a friend, saying of me, “He will find the road steeper and more rocky than others may, for, as I have told you, he made the fundamental error of being christened Cesar-Auguste, and, in addition, I fancy he is lacking in that convenient social sense that opens all doors before him.”

Image: Photo of composer César Franck playing the organ

His words suggested that I was not comfortable under a spotlight, and it would ring true. Although I wanted to succeed, I found it difficult to enjoy the popularity and fame of being a composer and musician who played virtuoso pieces, even when some were my compositions.

As a child prodigy, I was pushed by my father into performing rather than being asked. His parental coercion had the domino effect of motiving me to create a very different career as an adult.

César Franck Composes his Oratorio, Ruth

In 1843, at age 21, I began composing my first oratorio, Ruth. It was not as successful as I had hoped, since at the time, Paris was entering the romantic era of music, and Ruth was inspired heavily by music of the classical period. Later, though, a critic said, “M. Cesar Franck’s Ruth will live! It must be heard, acclaimed again and often, in Paris and all centers of art… it must be heard for the honor of our country’s symphonic music.”

Due to the lack of success Ruth brought, I decided to temporarily retire from public life and tours to concentrate on my compositions. My father was not best pleased about the decision, but I was ready to start anew alone at twenty years old.

Image: Album cover of Ruth, César Franck’s first composed oratorio

Next, I began composing Le Valet de Ferme but stopped before completing the composition. “It is not worth printing.” I was still unsure of where I wanted my career to lead, and I suppose composing Le Valet was the push I needed to know I made the right decision in retiring from public life to devote a great deal more time to writing music.

César Franck Breaks Off Relations with His Parents & Marries

Shortly after, I completely broke off relations with my parents. After being unable to make a lasting impression on audiences during my performances, my father began to suspect a woman was the reason why. He found a piece I had dedicated to a “Mlle. F. Desmousseaux, in pleasant memories.”

I had met Eugenie-Felicite-Caroline Saillot at the Conservatory. She was the daughter of a family who was part of the Comedie-Francaise Theatre Company. Felicite had been a former pupil of mine. I had taught her piano, harmony, and counterpoint. My father was less than thrilled with the idea of me having a relationship with someone who might distract me from his plans to support him, so he tore the composition into pieces.

On my twenty-fifth birthday, I told my father of my intentions to marry Felicite. I had just become an assistant organist at the Norte-Dame-de-Loretta church in 1847, and the newfound financial stability gave me a yearning for independence like never before. My father was speechless. I told him the marriage would go forward, whether he approved or not.

Image: Painting depicting the 1848 Revolution

On the day we married, February 22, 1848, shortly before arriving at the church, the 1848 Revolution had begun. Our wedding procession had no choice but to pass through the marching, shouting, and singing of hundreds of protestors.

About the incident, my student, the composer D’Indy later wrote, “the revolutionaries willingly helped the couple to make their way over these improvised fortifications.”

To our surprise, both my parents had begrudgingly accepted our wedding invitation, and they stood waiting at the church. Even more surprising was how happy our marriage was, despite beginning it on a day of political revolution!

César Franck’s Career as an Organist for Paris Churches & Cathedrals

There was only a second love in my life after my wife, my love for the organ. In 1853, I left Norte-Dame-de-Loretta and moved to Saint-Jean-Saint-Francois-au-Marais church as their primary organist. The organ installed there was of much better and higher quality. “My new organ— it sounds like an orchestra!” Becoming a primary organist made it obvious that my vocation should be as an organist, and that was where I ended up leading my career.

At Notre-Dame, I had become good friends with my superior, Alphonse Gilbert. A few years later, he influenced the church elders to grant me the position of primary organist at Saint-Jean. In my younger years, I found that although I had never been as good on the organ as I was at the piano, becoming a primary organist improved my skills. Loving the instrument changed my life and career. “If you only knew how I love this instrument… it is so supple beneath my fingers and so obedient to all my thoughts!”

During my time as a primary organist, a new technique began to sweep the nation. I was determined to jump on the pedalboard’s popularity and purchased my own with which practice. The pedalboard gave the organ more flexibility for performing, and I wanted to be skilled in both keyboards for my hands and keyboards for my feet.

Due to my work with the pedalboard and my growing popularity as an organist, I became a very well known performer of Cavaille-Coll instruments. Cavaille-Coll hired me to play their new ones at inaugural concerts.

Image: Photo of the organ at Saint-Jean-Saint-Francois-au-Marais Church

In April 1866, Franz Liszt attended one of my performances, and afterward, he told me, “How could I ever forget the man who wrote those trios?” My reply was, “I fancy I have done rather better things since then.” It pleased me that he still remembered me from all those years ago, and the trios I had specifically composed to impress him had a lasting effect.

César Franck Writes his Unsuccessful Composition, Les Beatitudes

I continued to compose for a few years, but nothing ever came of my work. It wasn’t until I began Les Beatitudes that I hit my stride. It took ten years to compose, from 1869 to 1879. I based my work, The Beatitudes, based on the eight beatitudes of Jesus and was my longest work yet, at almost two hours. I first performed it at my home, to a private audience.

Its public premiere, however, was unsuccessful. D’Indy would later say: “This personification of ideal evil — if it is permissible to link these terms — was a conception so alien to Franck’s nature that he never succeeded in giving it adequate expression.”

The premier public performance Les Beatitudes was delayed partly due to the beginning of the Franco-Prussian war. Like what I had done during the 1848 Revolution, I composed patriotic pieces. Because of the Franco-Prussian War, I lost several students, partly to their participation as soldiers fight or because they fled. Unfortunately, we hit a financial struggle during this time, and with the Conservatory closed, I relied heavily on my creative output to create an income.

Image: Album cover to Les Beatitudes, composed by César Franck

Cesar Franck’s Membership to Societe Nationale de Musique Helps Him as a Composer

Shortly after, I became a member of the Societe Nationale de Musique. Founded on February 25, 1871, the Societe National de Musique was steadfast in bringing a larger audience and awareness to orchestral music and French music in general. “They were determined to unite in their efforts to spread the gospel of French music and to make known the works of living French composers… According to their statutes… they intended to act ‘in brotherly unity, with an absolute forgetfulness of self.’”

The Societe’s first concert on November 17, 1871, featured my My Trio in B flat major.

The Professorship of Cesar Franck Delayed Due to His Lack of French Citizenship

In 1872, Paris Conservatory faculty members nominated me to succeed Benoist as an organ professor at the Paris Conservatory. However, it was only then that I found out I did not hold French citizenship. I thought I was a French Citizen, as my father had applied and received citizenship, which extended automatically to me.

I was unaware that my status as a French citizen had expired when I turned twenty-one years of age. Although the Conservatory held my position until naturalized, I couldn’t take on the job for a year.

When I finally was permitted to teach, I became very popular with the Paris Conservatory’s students, but I struggled with the faculty. I did not teach in the more formal, traditional way and regular way, but how I taught appealed to the students. Unfortunately, I mentored my students in ways that gave rise to jealousy from several of the other professors who couldn’t build a relationship with their students the way I had done.

I believe I had such a great relationship with my students because I involved them in everything. One music historian wrote, “When Franck was hesitating over the choice of this or that tonal relation or the progress of any development, he always liked to consult his pupils, to share with them his doubts and to ask their opinions.”

Image: Photo of composer, César Franck

Cesar Franck Composes Les Eolides

In 1875, I began working on a new piece inspired by Leconte de Lisle’s poem when I took a holiday to Languedoc. I quickly finished it by September 1875, and it would become Les Eolides, inspired by the story of Aeolids, the daughters of Aeolus. Since the Societe did not organize orchestral works by then (they would, later, in the 1880s), I found it challenging to arrange a premiere performance. It finally premiered in 1877, in the Salle Erard in Paris under Édouard Colonne.

Image: Album cover of Les Eolides, composed by César Franck

Cesar Franck Uses His Inner & Outer Struggles as a Source of Inspiration for His Composition, “Psyche”

The dissent from faculty members regarding how I taught continued. My wife, Felicite, believed that I should carry on as usual and disregard it. But I found myself caught in a tangle of worries about my teaching position’s security—this concern combined with my growing uncertainty about my unique stylistic approach to music. With Les Beatitudes stirring controversy and its unsuccess, I began to question my talent as a composer.

In 1886, I took those worries and uncertainties and composed Psyche. Based on the pagan myth of Psyche, it tells the story of Aphrodite, who, jealousy of Psyche, convinces her son Eros to curse Psyche so that no one will ever fall in love with her. Unfortunately, when he shoots his arrow, he wounds himself instead.

I worked with this story, based on the only surviving ancient Roman novel by Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis, and I divided the story into three parts. First, the introduction, followed by The Union of Lovers and ending with a slow, soft composition of clarinets, horns, violins, and violas.

Psyche premiered in 1888. A historian, Henry Villars, said, “The audience was swept away, and Franck was glowing with happiness in his box.”

But not everyone felt the same way. The religious aspects of the symphonic poem stirred unease with the audience. My wife, for example, found it to be too sensual.

D’Indy, however, was for it, saying, “Nothing of the pagan spirit about it… but, on the contrary, is imbued with Christian grace and feeling…”

Cesar Franck Composes His Famous Symphony in D Minor

Shortly following the controversy of Psyche, I received even more dissent and criticism upon the release of my Symphony in D Minor. I had begun composing it in 1886 and finished in 1888, shortly after my completion of Psyche.

Symphony in D Minor became my most famous orchestral piece. Partly because of the music’s nature and the Societe’s political agenda, Symphony in D Minor has become my best know composition.

Image: Album cover to Cesar Franck’s Symphony in D Minor

Premiering Cesar Franck’s Symphony in D Minor Amid Controversy

Around the time of composing my Symphony in D Minor’s premiere time, the Societe Nationale de Musique had begun accepting German music for performance, which caused an ideological split among our members.

Rather than one group of people enjoying music together, French nationalist members opposed to accepting foreign music split off. Members, including the very influential composer and head of the Paris Conservatory, Saint-Saens, couldn’t bear the change, decided to step away, and I assumed the Societe’s presidency.

The controversy caused by this split became toxic to harmonious relationships, infiltrating the Paris Conservatory, making it impossible for me to perform Symphony in D Minor there. Suddenly, conductors and orchestras alike rejected opportunities to perform my music; not until I convinced the Conservatory’s orchestra to play it did my Symphony in D Minor see the light of day.

Unfortunately, because even The Conservatory’s orchestra did not want to perform my symphony, the reception was not what I initially envisioned. Primarily influenced by politics, Le Menestrel called it, “Morose… Franck had very little to say here, but he proclaims it with the conviction of the pontiff defining dogma.” It would be the last piece I ever published.

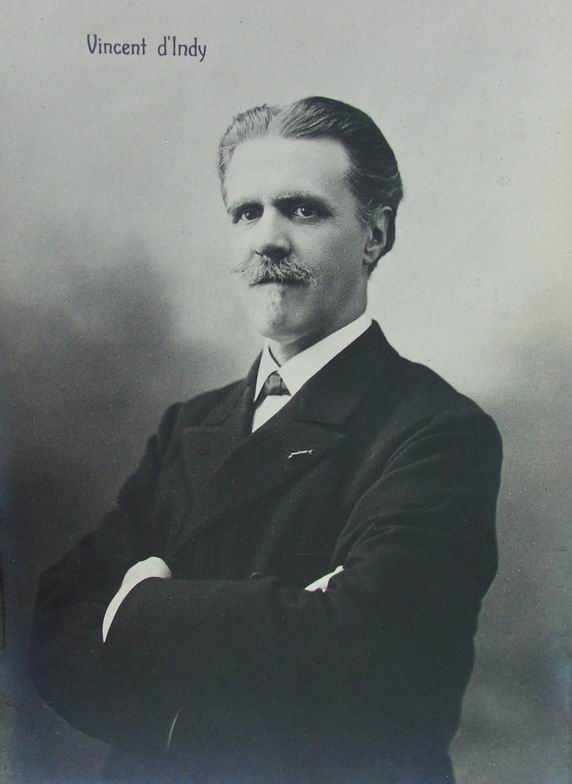

Cesar Franck Described by His Student, Vincent D’Indy

My most influential student, Vincent D’Indy, studied with me for a long time. He and his fellow students seemed to be bemused yet appreciative of my work ethic and my regular schedule of performing on organ, teaching privately, and still having time for my wife and family as well as composing. You see, I had to work for a living. I loved my wife and family. Therefore I had to be strict with my schedule to earn enough money and still compose.

My typical workday was as follows: Starting my day at 5:30 am, I devoted the first 2 hours to music composition. Around 7:30 am, after a small breakfast, I gave music lessons throughout Paris, teaching piano and organ to beginners through advanced pupils. I also taught in colleges, boarding schools. I walked and traveled by omnibus from appointment to appointment.

In the evening, I returned home for my evening meal, along with some vital time to be with my wife and family. After eating most evenings, I copied my scores, wrote out the parts, and orchestrated my compositions. Additionally, I devoted some of my evenings to teaching advanced organ and music composition students.

About my schedule, my primary student Vincent D’Indy said, “In these two evening hours of the morning – which were often curtailed – and in the few weeks he snatched during the vacation at the Conservatory, Frank’s finest works were conceived, planned, and written.”

Image: Photo of Vincent D’Indy, Franck’s student

A Horse And Cart Run Over Cesar Franck Leading to Ill Health & Death

In July 1890, I was in a horse and cart accident. Although I walked away from the incident, I became increasingly weakened after that, and I had to retire from public performances and take a break from the professorship to recover. To relax and recover, I took a holiday to Nemours. Newly inspired, I began to compose once again.

Returning to the Conservatory in October of that same year, I fell ill after catching a cold. The cold turned into pleurisy, and I passed away on November 8, 1890. The funeral took place at the Sainte-Clotilde church, and I was first buried at Montrouge and later moved to Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

Image: Statue of Cesar Franck at the Square Samuel-Rousseau, in Paris, France.

Composer Vincent D’Indy Laud’s his Music Composition Teacher, Cesar Franck

“Untiring assiduity in work, modesty, a fine artistic conscientiousness – these were the salient features in Fracnk’s character. But he had yet another quality – a rare one – namely, goodness: a goodness that was serene and indulgent.

The word most often used by the master was the verb “to love.” “I love it,” he would say of a work, or even of a detail which appealed to his sympathies; and in truth his own works are all inspired by love, and by the power of love and his high-minded charity he reigned over his disciples, over his friends, and over all the music transitions of his day who had any nobility of mind; and it is out of love the him that others have tried to continue his good work.”

Please find compelling quotes of Cesar Franck here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- Famous Composers by Nathan H. Dole

- The Lives of Great Composers by Harold C. Schoenberg

- Great Composers 1300-1900 by David Ewen

- The Pan Book of Great Composers by Gervase Hughes

- Cesar Franck: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/César_Franck

- Cesar Franck: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cesar-Franck

- The Musical Quarterly: https://www.jstor.org/stable/738541?seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Psyche et Eros: https://www.indianapolissymphony.org/about/archive/program-notes/cesar-franck/psyche-et-eros