Bela Bartok: Composer, Pianist, Musicologist & Piano Teacher

This biography of Bela Bartok is told in the first person as if Bartok returned from the afterlife to tell us the story of his life. Along with the help of the British writer, Aly Locatelli, I wrote this biography using multiple sources so it may be as accurate as possible. Note: Where Bartok is directly quoted, (as obtained from references), his actual words are contained withing quotation marks. Thank you, Richard J. Chandler, BA, MA

Bela Bartok: Childhood and Early Compositions

The first musical instrument that I learned to play was a drum. “I got a drum when I was two. Mother says I drummed all the time. I tried out rhythms on it.”

Later it was “…the piano. I must have been four years old. Mother tells this also. I plunked out Hungarian popular songs with one finger.”

I liked performing for mother – she seemed proud of me, of what I could do. Father enjoyed writing and playing music, too. Mother said, “learn to play the piano, my son. If company comes over and they ask you to play the piano for a dance, what a shame it would be to say you don’t now how. And how nice if somebody plays the piano.” Mother began teaching me properly the next year when I turned five.

After at I remember “my first printed music. I got it for my fifth birthday. I remember this. My father … loved music and composed. My mother liked to play the piano. Both of them encouraged me. The practicing skills bored me. Like every child, I was bored to death.” After my father died when I was seven years old, my mother made her living as a traveling piano teacher.

I started to compose “when I was nine. These were sort of dance pieces, Viennese waltzes, … Sonatina’s, imitations of Mozart.” But the compositions that I first considered as truly having my voice were the fourteen pieces for piano followed my 1st String Quartet. When I compose, “I don’t like to mix work. If I begin something, then I live only for it until it is finished.”

At eleven years old, I performed one of my compositions, The Course of the Danube, live on stage in Nagyszõlõs. It was surreal – all these people were there for me and my music!

Image: Hungarian Composer & Musicologist, Bela Bartok high school photo

Bela Bartok’s Discovery of Folk Music

At sixteen, I fell in love with folk music. I was in Transylvania, and I could hear music – unlike any other music I had ever heard. It was a woman singing. I followed the sound and found her. I quickly wrote the melody down as best I could.

My journey in ethnomusicology began accompanied by my dear friend Zoltán Kodály. This kind of music we called folk music. It was light-hearted and upbeat, yet it sang to the soul. Together, we traveled throughout Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Slovakia with our Edison phonograph. I collected songs from villagers by asking them to sing into it, and the bulky machine recorded them on wax cylinders. We carried on, even traveling as far as Turkey, forever chasing songs, learning the core of folk music. I listened to those recordings again and again. That way, I learned from them and began composing my folk-influenced melodies.

“Folk melodies are the embodiment of artistic perfection of the highest order; in fact, they are models of the way in which a musical idea can be expressed with utmost perfection in terms of brevity of form and simplicity of means.” This is how both volumes of For Children was born. My intent was for the work to embody artistic perfection, with perfect accompaniments.

In my 1926 interview for the Kassa Journal, I summed up my thoughts on folk music: “As everyone knows, peasant music of various peoples has been a great influence on me. I am interested not simply in their musical motives but also in their formal structures, which particularly fascinated me. Had I obtained them only second-hand, these songs’ influence would not have been so immediate and strong. But because in the course of my collecting I simultaneously received impressions of both the songs and their environment – the atmosphere of the village – the experience had a full impact.”

Image: Bela Bartok records folk singers of Hungary & Transylvania

The Violinist, Stefi Geyer, Rejects Bartok as a Romantic Partner

I met the first romantic love of my life, violinist Steffi Geyer, while a student at the Budapest Conservatory of music. We became acquainted, but became serious with each other after I graduated. She came from the devout Catholic family; I was quite vocal in my critique of religion. My strong views contributed to her distancing from me. At that time, I loved her, and how beautifully she played.

I was writing my violin Concerto for her when our relationship became ever more strained. My love and anguish were apparent in these excerpts from 1907 letters written to her: and “Now, I should compose a picture of the indifferent, cool, silent Stefi. Geyer. But this would be hateful music.” “You are a dear, a good, a fairy-like, an enchanting girl who has only to draw a few lines to chase the dark, grimly sw you and irling clouds from the sky and makes the bright sun shine on me. “You are a taciturn, a bad, a cruel, a miserly girl to begrudge me your powers of enchantment!” The loss of Sefi’s affection was difficult for me. Thankfully a new love entered my life.

Image: Photograph of violinist Stefi Geyer sitting holding flowers

Bela Bartok Starting a Family: Marriage, Ballets, and Opera

I was twenty-eight years old when I fell in love again with a piano student of mine. Márta Ziegler had stolen my heart. She was competition for my time to compose music, but also an inspiration. I wrote my only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle, for her. “In vain, I have dreamt too much of you. Waited too long, Staring into the distance…”

I was disappointed when the Hungarian Fine Arts Commission rejected my opera, but it did not stop me from trying again. After all, “competitions are for horses, not artists.”

The musical compositions of Igor Stravinsky, particularly his use of folk elements, intrigued me. Márta recalls that during rehearsals for the Bluebeard’s Castle premier in 1918, I “carried the four-hand piano score of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring around with me constantly, waiting for an opportunity to play it for the intendant to persuade him to stage the ballet.”

I defended Stravinsky to English critic Philip Heseltine who had written a disparaging article about Stravinsky in the publication, The Sacbut, saying: “Concerning Stravinsky, I only know his arrangement for piano of The Rite of Spring, The Firebird and the score of his 3 Japanese Songs. But these three works have made a great impression on me.”

I continued to collect folk music and compose, biding my time for other opportunities that might come my way. After some traveling, (Moldavia, Wallachia, and Algeria), I was forced to return home to Budapest by the outbreak of World War I.

Once my expeditions had come to a stop, I began writing again, inspired. And thus The Wooden Prince was born, a ballet, and String Quartet No.2. Debussy influenced both pieces. The latter was unlike anything I had composed before. It was sorrowful, mournful but with a hint of hope for the future. It reminded me of my disappointments, my knockdowns and the consistent way in which I picked myself up and carried on.

My relationship with Márta burned quickly. We married soon after meeting, and I wrote many pieces for her: in Burlesque No. 1, ‘Quarrel’ was dedicated to her.

Like most things, though, we encountered problems, Márta and I. It wasn’t long before I fell in love once again – another woman, a student. I wrote Five Songs Op. 15 with Kárla’s help — she wrote the words to four out of five of the songs. Because of the potential scandal, I claimed to have written them myself.

Image: Photo of the opera Bluebeard’s Castle the only opera by Bartok

Bela Bartok’s Religion: From Atheism to Unitarianism

In 1916, Márta, who had more common religious beliefs, consented for my son (Béla III) and myself to convert to Unitarianism after years of atheism on my part. Soon after, I had found myself fascinated with Freikopekultur, a community living approach that meant free body culture. Márta once said: “Bartók would exercise naked each morning and take the sun as early as possible. He could stand the sun particularly well, and while sunbathing, he would go on working, studying languages, scoring his compositions.”

Marta had much to contend with. Over time, we had difficulties. In 1923, I had to send her away. It was her idea to file for a divorce. Shortly after my marriage ended I married again – Ditta – and my second son, Péter, was born a year later.

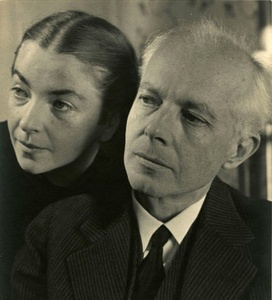

Bartok’s Second Wife, Ditta

Shortly after my marriage ended I married again – Ditta – and my second son, Péter, was born a year later.

Image: Photograph of Bartok and wife second wife, Ditta

A Scandalous Ballet by Bela Bartok

Although I had written it eight years prior, in 1926, my ballet, The Miraculous Mandarin, received its first performance. This composition, influenced to some extent by Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, and Richard Strauss, had previously been deemed ‘too sexual in nature’ to be performed. It was a one-act pantomime based on the story by Melchior Lengyel. It did end up causing a scandal, and was subsequently banned in Germany on moral grounds!

In 1927 and 1928, I wrote my Third String Quartet and Fourth String Quartet. I even returned to my journeying in 1936, where I traveled to Turkey and collected and studied folk music, and later worked alongside Turkish composer Ahmet Adnan Saygun.

Bartók’s Fight: His Views on Nazi Germany and His Fight with Totalitarian Regimes

The Hungarian government’s facilitation and co-operation with the Nazis to be less than desirable. Before then, I had performed in Germany many a time, up until Adolf Hitler became chancellor in 1933. My anti-fascism caused problems, and I ended up refusing to play in Germany, after over forty performances there. Since the Reich wanted performers from supportive countries – and Hungary was a supporter in and of itself – a number of my scheduled performances and lectures never took place.

It was when my royalty rights association, TKM, based in Vienna, decided to ask its members for proof of ethnicity that I decided enough was enough. Repeatedly I was asked to prove I wasn’t Jewish; I refused.

In 1938 I wrote a friend living in Switzerland saying: “There is the imminent danger that Hungary will surrender to the system of robbery and murder. How I could then continue to live or – which amounts to the same thing – work in such a country is quite inconceivable.”

Shortly after, my publishing house was ‘Nazified’. Germany annexed Austria. Boosey & Hawkes in London – the UK’s agent of my publishing house Universal Edition – were aware of what was happening, and had created a plan to offer help to Jewish composers and others at risk, people like myself. Music publisher Ralph Hawkes even flew over to Hungary to meet Zoltán Kodály and me to arrange for Boosey & Hawkes to become our new publisher.

However, I was not prepared to leave Hungary without a fight. I joined a group of non-Jewish intellectuals, and we began protesting when the Jewish Laws, (the Hungarian version of the Nuremberg Laws), began taking effect in 1938. By my side were renowned people such as Dénes Koromzay, a violist in the Hungarian String Quartet who had spent the war in the Netherlands.

Because I was so direct and outspoken, it became critical that I make preparations to leave with my family should the need arise. I sent my manuscripts to Boosey & Hawkes via Switzerland, in case the Gestapo came knocking on my door one day. I wanted to leave Budapest right away and begin somewhere anew but did not feel comfortable leaving my mother behind.

I began writing String Quartet No. 6 in Italy alongside Ditta in the year of 1939. Unbeknownst to me, it would become the final piece I ever finished in Hungary. It is melancholy, lamenting. When my mother died in December of that year, I rewrote the last movement as an elegy. In 1940, with World War II’s outbreak, everything changed.

Image: Photo of Bartok standing with a cane and holding a coat

Bela Bartok’s New Beginning: Moving and Settling in New York City

In that year (1940) I received an invitation from the University of Columbia, New York, to work as a research fellow in their ethnomusicology department.

After dissolving my contract with Universal Edition, my wife Ditta and I emigrated to New York, taking up the University of Columbia on their invitation. We arrived on a steamer from Lisbon. My younger son, Péter, joined the US Navy while Béla III remained in Hungary.

I could not ignore what was happening back home. Hungary declared war on the United States. I protested and lost my Hungarian citizenship for speaking out about the political situation in Hungary. This loss saddened me.

I never felt at home in New York City. Although America knew my music, I found it challenging to compose and to play once again with the same freedom as I had in Hungary. Although financially we struggled, the support of friends got us through some difficult times. I was always a proud man and refused charity. Later, Ditta and I began working on a collection of Croatian and Serbian folk songs. I kept myself busy with teaching and performance tours as my music composition royalties continued to grow.

I composed Concerto for Orchestra in 1943, a piece that was commissioned by the esteemed Serge Koussevitzky, a conductor, composer, and double-bassist. The commission by the Koussevitzky Foundation later sparked Sonata for Solo Violin and Piano Concerto No. 3. The Concerto for Orchestra premiered in 1944, at the Symphony Hall in Boston, played by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Serge Koussevitzky.

Bela Bartok: Health and Death

My health problems began a few years after we arrived in America. At first, it was a stiffness in my shoulder. Next came the fevers. Eventually, the doctors’ diagnosed leukemia, but it had already advanced past the point of effective treatment. It was amusing to note that, knowing my body was failing me, I suddenly found my creativity once again. I composed my final pieces thanks to violinist Joseph Szigeti and conductor Fritz Reiner.

Image: Composer Bela Bartok sitting at grand piano

Shortly after becoming an American citizen, at age 64 years of age I died from complications of leukemia in a New York City hospital. I stated in my will that I “refused to have a street named after me in Hungary as long as there was a street or square named after Hitler or Mussolini.” Although initially buried in America, my sons had my body exhumed after the communist era ended in Hungary, as the government requested that my remains be returned home for a state funeral. My body was transported back to Budapest for a second burial in my homeland.

My student, Tibor Serly, and my son Péter completed my incomplete works which were later published. Hungary named six streets after me, and I appear on a Hungarian 1000-forint banknote.

“I cannot conceive of music that gives absolutely nothing.”

“Bartok was a tiny, frail man with explosive psychic force, prepared to go his own uncompromising way even if his music was never played. A stubborn integrity and an all-encompassing humanism animated the man, and he would not swerve from his ideal of truth, even when it involves resisting the Nazis and making a new home elsewhere.”

“He was a composer who merely happened to believe that folk music in its purest state was a fructifying force. Thus he wanted to be assessed as a composer, not as a folklorist. He composed rugged music that asked no quarter of anybody, and his best works are the reflection of one of the strongest and most uncompromising musical minds of the 20th century.”

-Harold C Schonberg Senior music critic for the New York times for two decades.

Please find compelling quotes of Bela Bartok here on his quotes page.

Sources:

Béla Bartók, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B%C3%A9la_Bart%C3%B3k

Béla Bartók, Boosey & Hawkes: http://www.boosey.com/pages/cr/composer/composer_main.cshtml?composerid=2694&ttype=BIOGRAPHY

Music and the Holocaust: Béla Bartók: http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/resistance-and-exile/bartok-bela/

Béla Bartók: The Father of Ethnomusicology: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=musicalofferings

Concerto for Orchestra: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concerto_for_Orchestra_(Bart%C3%B3k)

Rebound from a Breakup: Béla Bartók and Márta Ziegler: http://www.interlude.hk/front/rebound-break-bela-bartok-marta-ziegler/

Béla Bartók on Classic FM: https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/latest/inspiring-composer-quotes/bela-bartok/

Great Female Violinists: A List https://songofthelarkblog.com/tag/geyer-stefi/

Bartok and His World, Edited by Peter Laki. Princeton University Press