Georges Bizet Early Life and Family

I was born in Paris on 25 October 1838, and was originally registered as Alexandre César Léopold. I was baptised ‘Georges’ on March 16, 1840, a name gifted to me by my godfather which stuck better than my original name. My father had been a hairdresser and wigmaker, but turned to a career of music when he decided to become a singing teacher with no formal training. In his time, he published at least one song.

My father married my mother, Aimée in 1837, a year before I was born. Her family was unhappy with the match, and considered him unfit to marry her. The Delsartes were a cultured and musical family, with their children pursuing fruitful careers in music. My mother was a very talented pianist, and her brother François was a distinguished singer and teacher, with notable performances in the courts of Napoleon III and Louis Philippe.

However, their marriage was a happy one. I was an only child, and I showed musical talent very early on. Picking up musical notation from my mother, she decided to begin giving me my first piano lessons. Other times, I would listen in on lessons my father gave and learned how to sing difficult songs accurately from memory, and how to identify and analyse complex chordal structures.

At the age of nine, my parents decided I was ready to begin my studies at the Conservatoire. The minimum age of entry was ten, but Joseph Meifred, who was a member of the Conservatoire’s Committee of Studies, was so awestruck by my talent and skill that he waived the entry rule, promising me a space as soon as one became available.

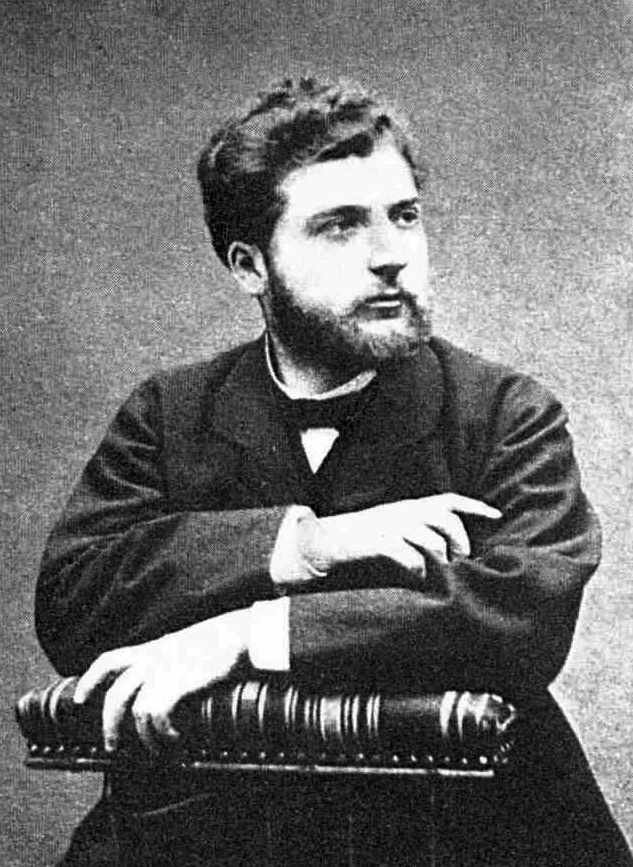

Image: Photograph of a young Georges Bizet

The Conservatoire: Georges Bizet’s Prizes and Growth

I was finally admitted on October 9, 1848 — just shy two weeks of my tenth birthday. The Conservatoire challenged me in ways I did not know could be possible, and I made an early impression. In the first six months, I had won the first prize in Solfège, a feat that earned me private tutelage with Pierre-Joseph-Guillame Zimmerman, who was the former professor of piano at that time.

Zimmerman tutored me in counterpoint and fugue, the lessons continuing until his passing in 1853. During these private lessons, I met his son in law, the composer Charles Gounod. Gounod and my friendship was rickety at best, hot and cold, with it more strained than not in later years, but he was a great influence on my musical style. I also met Camille Saint-Saëns in those classes, who also became a good, close and influential friend.

During my time at the Conservatoire, I was also under the tutelage of Antoine François Marmontel, the professor of piano, and it was with him that my pianism developed very quickly.

In 1851, I won the Conservatoire’s second prize, and in 1852, I won first prize. I was thirteen and fourteen, respectively. After winning first prize, I wrote to Marmontel, excited to share my victory with him: “In your classes one learns something besides the piano; one becomes a musician.”

A year after winning first prize, in 1853, I joined Fromental Halévy’s class of composition. The quality of my music improved drastically, and it was during these lessons that Petite Marguerite and La Rose et l’abeille were created, and published in 1854, when I was sixteen.

Also at sixteen, I prepared four-hand piano versions of Gounod’s works. One being the opera La nonne sanglante and the other Symphony in D. It was working on the latter that inspired me to compose my own symphony at seventeen years old. It had a close resemblance to Gounod’s, and was subsequently lost. It remained undiscovered until 1933.

Image: Photograph of Composer, Charles Gounod

Georges Bizet’s Time at The Prix de Rome

In 1856, I competed for the prestigious Prix de Rome, with an unsuccessful entry. That year, the musician’s prize was not awarded to anyone who had entered the competition. Instead, I entered an opera competition, which was organized by Jacques Offenbach, with a prize of 1,200 francs. I won alongside Charles Lecocq, who later made shocking claims that I only won because Halévy had been one of the judges.

Although the claims were unnecessary, winning the competition led me to become a regular guest at Offenbach’s friday night dinner parties, where I met a number of musicians of varying degrees of success. My favourite meeting, though, was with Gioachino Rossini, who gifted me a signed photograph. “Rossini is the greatest of them all, because like Mozart, he has all the virtues.”

I entered the Prix de Rome again in 1857, at nineteen. With Gounod’s approval, I submitted the cantata Clovis at Clotilde by Amédée Burion. I won first prize, and received a financial grant for five years. Under the conditions of the prize, I was to spend two years in Rome, a third in Germany and the last two in Paris. Throughout this time, I was to submit a piece of original work each year to the Académie.

Before my departure, my winning cantata was performed at the Académie to enthusiastic reception.

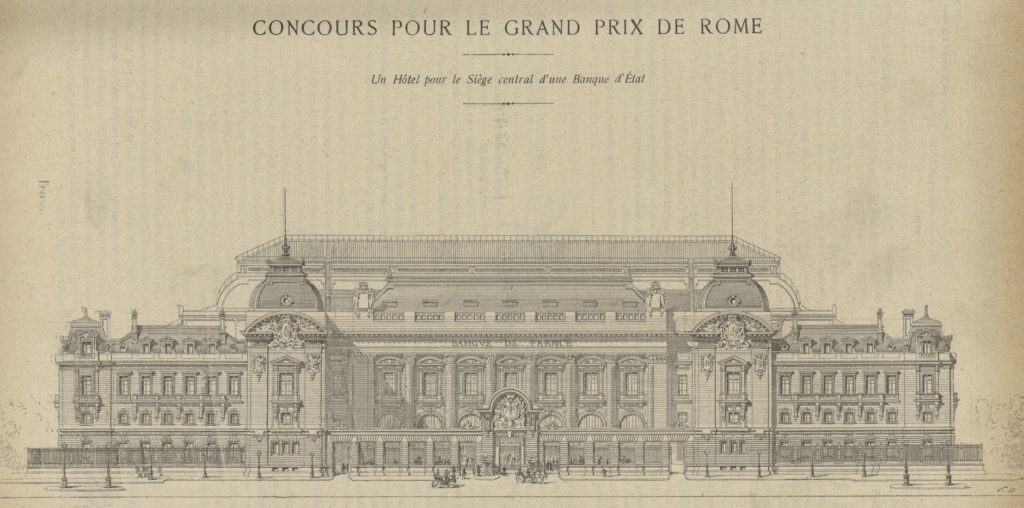

Image: Drawing of the Prix De Rome building

Rome: Georges Bizet‘s Inspirations and Failures

I arrived at Villa Medici on January 27, 1858. It was a paradise housing the French Acedémie in Rome, and the perfect place for myself and the other laureates to pursue our artistic endeavors. The problem was I became too caught up in my newly found social life that the only piece I composed in the first six months of my stay in Rome was a religious piece named Te Deum.

Te Deum did not impress the judges, and I was discouraged enough that I vowed never to write religious music again. Te Deum remained unpublished until 1971.

In the winter of 1858 to 1859, I worked on my first envoi for the Académie. It was meant to be a mass set to Carlo Cambiaggio’s libretto Don Procopio, but after my vow, I decided to go another way and effectively bent the rules. I ended up submitting something slightly different, and to my surprise, the Académie like it. They said I had an “easy and brilliant touch” and a “youthful and bold style.”

For my second envoi, I had decided to submit a semi-religious piece so as not to push the Académie’s tolerance. It was called Carmen Saeculare, a secular mass on a text by Horace, and it was intended as a song to Apollo and Diana.

Unfortunately, this piece does not exist. I never started it. Abandoning ambitious projects became a part of my life while in Rome. I discarded at least five operas, two attempts at a symphony and a symphonic ode on the theme of Ulysses and Circe. I managed to complete only one piece in Rome, a symphonic poem named Vasco da Gama, which replaced Carmen Saeculare as my second envoi.

Vasco da Gama was well received by the Académie, but it was quickly forgotten afterwards.

Georges Bizet Discovering Italy

In the warmer months of 1859, myself and my companions began visiting places around Rome such as Frosinone. Inspiring places, rich in history. In August, I ventured to Naples and Pompeii, where the latter inspired me so greatly I began sketching a symphony. This would later become Roma, but at the time I made very little headway and did not complete it until 1868.

Returning to Rome after my trip to Pompeii, I was successfully granted a third year in Italy after my request instead of going to Germany. This was so I could “complete an important work” that I don’t believe I ever finished.

Unfortunately, when I was visiting Venice with Ernest Guiraud, I received news that my mother had taken gravely ill, and promptly returned to Paris.

Bizet Returning to Paris: Grief and Starting Over

Once I returned to Paris, I had two years left of my grant and was financially stable enough to ignore the difficulties other composers were facing at the time.

March 31, 1861, I attended the premier of Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser. I witnessed riots in the audience led by Jockey-Club de Paris, a prestigious gentlemen’s club. It was this premier that changed my mind about Wagner’s music. Where before I had thought of it as merely eccentric, I now believed Wagner to be “above and beyond all living composers.”

At a dinner party that same year, I impressed Franz Liszt by playing a very difficult piano piece by himself flawlessly on my first attempt. Liszt said, “I thought there were only two men able to surmount the difficulties… there are three, and… the youngest is perhaps the boldest and most brilliant.” I very rarely demonstrated my piano skills, happy to compose instead. His admiration of my talent was an honor.

While in Paris, I began work on Roma again and my third envoi, but it all came to a halt when my mother died in September 1861, when I was twenty-three. Her death was difficult for me, and I was plunged into a deep depression.

Eventually, I submitted a trio of orchestral works as my third envoi: La Chasse d’Ossian, a scherzo and a funeral march. All three pieces were either lost or reworked into later pieces, such as the scherzo that was later incorporated into the Roma symphony.

My final envoi was a one act opera named La guzla de l’émir. It was accepted, and entered rehearsal at the Opéra-Comique in 1863, who was contractually obliged to stage pieces created by Prix de Rome laureates. However, when Count Walewski asked me to compose music for a three-act opera, I quickly pulled La guzla from the Opéra-Comique and reworked some of its parts to include them in what eventually became Les pêcheurs de perles.

Unfortunately, Les pêcheurs received lukewarm reactions, and its run ended after only eighteen performances.

Image: Photograph of Bizet’s Les_pêcheurs_de_perles scene from act II of the opera

Georges Bizet’s Scandal

In 1862, at twenty-four years old, I fathered a child with my family’s housekeeper, Marie Reiter. The boy was brought up as my father’s son, my half-brother, and it was not until she was on her deathbed that Marie revealed his true parentage.

Image: Photograph of Jacques Bizet, Georges Bizet son

Georges Bizet Teaching and Expanding Knowledge

After the grant from the Prix de Rome expired, I realised that composing alone would not make me a sustainable living. I took on students for both piano and composition, and also worked as an accompanist for various rehearsals and auditions. This included Berlioz’s L’enfance du Christ and Gounod’s Mireille.

For a short while, I was also a music critic for La Revue Nationale et Étrangère under the pseudonym Gaston de Betzi.

My main work, however, was making piano transcriptions for hundreds of operas and preparing vocal scores. My gig at La Revue ended in August 1867 when I ended up arguing with the new editor, and quit.

Since 1862, I had worked on and off on an opera based on the life of Ivan the Terrible. When Carvalho failed to produce it as promised, I offered it to the Opéra who promptly rejected it.

In 1866, twenty-eight years old, I signed another contract with Carvalho for La jolie fille de Perth. Issues delayed its premier, but when it finally happened, La jolie fille was my best received piece thus far. At the same time as La jolie fille was in rehearsal, I had worked on a four-act operetta with three other composers, who each contributed a single act each.

It was titled Marlborough s’en va-t-en guerre and it was performed 13 December 1867, at the Théâtre de l’Athénée to resounding success. A critic said, “Nothing could be more stylish, smarter and, at the same time, more distinguished.”

Bizet Finishing Roma and an Unexpected Romance

I also finally finished my Roma symphony that year, but my successes were overshadowed by disappointments. Operas were abandoned and competition entries unsuccessful. My struggle with depression began to affect my creative success.

After Fromental Halévy’s passing in 1862, I was asked by his wife to complete his unfinished opera Noé. Halévy had left behind two daughters: Esther, who passed in 1864, and Geneviève. The trauma of losing her daughter only two years after her husband, and so young, caused a rift between Madame Halévy and Geneviève, and she had been living with other family members since the age of fifteen.

I declared my love for Geneviève, telling Galabert: “I have met an adorable girl, whom I love! In two years she will be my wife.” We became engaged shortly after, a feat that was not accepted or blessed by her family. They claimed I was not good enough for Geneviève, but contrary to what they thought or believed, we married anyway.

Our marriage was initially happy, but it was greatly affected by outside forces: Mme. Halévy’s constant interference and Geneviève’s nervous disposition, for example. However, I did my best to keep up good relations with my mother-in-law, corresponding with her weekly.

On February 28 1869, at thirty-one, the Roma symphony was performed at the Cirque Napoléon. I believed it to be a success, even informing Galabert of this.

Image: Photograph of Geneviève Halévy, Bizet’s wife

Georges Bizet and The Franco-Prussian War

A year after our wedding, I began a few projects — a dozen new operas such as Clarissa Harlowe — but the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war in July 1870 quickly put a stop to my work. I had to make a decision, and I quickly signed up with the National Guard. I wanted to defend my country.

During training, I was shocked at the quality of the equipment we were expected to fight with. The guns were outdated and dangerous — more so to us than the enemy. National mood depressed soon after, but I refused to leave Paris when the Prussian armies had surrounded the city. “I can’t leave Paris! It’s impossible! It would be quite simply an act of cowardice.” I wrote to my mother-in-law. I did not feel comfortable running away to England like Gounod had, when France had still so much to offer me.

When the Armistice was signed January 26, 1871, and the Paris Commune arose, I made the swift decision to escape to Compiègne, and then Le Vesinet with Geneviève. We were so close to the uprising we could hear the cannons and gunfire, and the army marching against the uprising. In another letter I wrote to my mother-in-law, I remember saying, “The cannons are rumbling with unbelievable violence.”

Georges Bizet and His Career Struggles

Afterwards, as Paris began to return to normal, I was supposed to become chorus-master at the Opéra, but the post went to Hector Salomon on November 1. With this new information, I began working on Clarissa Harlowe again and Grisélidis, but neither works were ever finished. Grisélidis had plans to be performed at the Opéra-Comique, but they fell through, and instead I concentrated my efforts on finishing Jeux d’enfants and the opera Djamileh.

Djamileh closed after only eleven performances. It was badly sung and staged, with the lead singer missing thirty-two bars of music at one point.

On July 10, my son Jacques was born, and I became a father at thirty-four. Later, Carvalho wanted incidental music for Alphonse Daudet’s play L’Arlésienne. Carvalho was managing the Vaudeville theater, and the play opened on 1 October. My music was dismissed by critics as too complex, but I refused to give up. I ended up incorporating music from the play into a four-movement suite, which was later performed under Pasdeloup in November to a more enthusiastic reception.

In the winter of 1872, I supervised preparations for a revival of Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette. He was still in England after escaping during the war, and asked me for my help, to which I’d responded, “You were the beginning of my life as an artist. I spring from you.”

Georges Bizet’s Opera, Carmen

In June of the same year, I told Galabert, “I have just been ordered to compose three acts for the Opéra-Comique. Henry Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy are doing my piece.” The project was Carmen, a short novel by Prosper Mérimée.

I began working on the music in the summer of 1873 but it was quickly suspended when management of the Opéra-Comique worried it would not be suitable for their audience. They normally provided wholesome entertainment for families, and Carmen was too “risqué.” Instead, I switched to working on Don Rodrigue only for it to be also set aside and never completed after the Opéra burned to the ground.

Needless to say, my years of struggle were far from over. After Adolphe de Leuven resigned as co-director of the Opéra-Comique, I finally finished the score for Carmen. He had been my only real obstacle. “I have written a work that is all clarity and vivacity, full of colour and melody.” Without Alphonse de Leuven as director, rehearsals for Carmen went ahead.

Célestine Galli-Marié was to sing the leading role. Our close relationship spurred rumours of an affair I neither confirmed nor denied. However, problems arose almost immediately as rehearsals began in October 1874. The orchestra claimed some parts of the score were unplayable and the chorus complained that they did not want to act as well as sing. It wasn’t until the lead singers threatened to withdraw from Carmen altogether that management and I made the changes requested.

Carmen opened 3 March 1875, the same day my appointment as Chevalier of the Legion of Honour was announced. Camille Saint-Saëns and Charles Gounod were both present at the premier, whilst Geneviève was too unwell to come.

Where Saint-Saëns was congratulatory, Gounod was not. He accused me of plagiarism, saying, “Georges has robbed me! Take the Spanish airs and mine out of the score and there remains nothing to Bizet’s credit buy the sauce that masks the fish.”

His reaction came on the back of reporters also reacting negatively to Carmen. Their claims were the heroine was too immoral, rather than a woman of virtue. They stated Carmen was “the very incarnation of vice.”

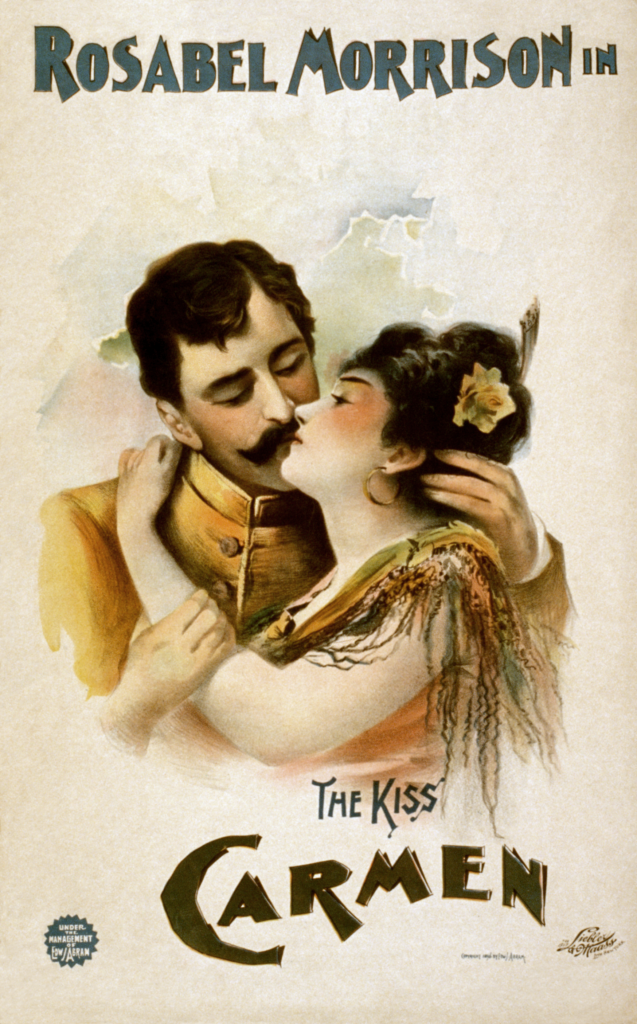

Image: Poster of the opera Carmen

Georges Bizet’s Disappointments and Ill Health

I became convinced of my failure. I could foresee a definite and hopeless flop. The years of struggle only deepened my depression, and in 1868 I admitted to Galabert that I had been suffering with abscesses in my throat. I suffered from attacks of what I called “heart angina” while completing Carmen, and again in late March 1875.

Carmen’s failure made me sicker and slower to recover, and I fell ill again shortly after in May. After that, I decided to retire to my holiday home in Bougival for a while, hoping a change of scenery and fresh air would make me feel better. Indeed, I did feel better, and decided to take a swim, only to then fall sick the day after with a high fever and pain. I had a heart attack.

Georges Bizet’s Death

I recovered temporarily, but on the day of my anniversary, June 3, I had another heart attack that proved fatal. I died at only thirty-six years old. The suddenness of my death fuellled rumours of suicide, and the news of my passing stunned the Paris musical world. That evening, the performance of Carmen was cancelled.

Over four-thousand people appeared at my funeral on June 5. It was held at Église de la Sainte-Trinité in Montmartre. My father led the mourners, and an organist played an improvisation on themes of Carmen in my honor.

Gounod gave the eulogy, saying I had been struck down just as I was becoming recognised for my talent. He then broke down and could not continue.

That night, a special performance of Carmen was held at the Opéra-Comique, and the press declared Georges Bizet a “master.”

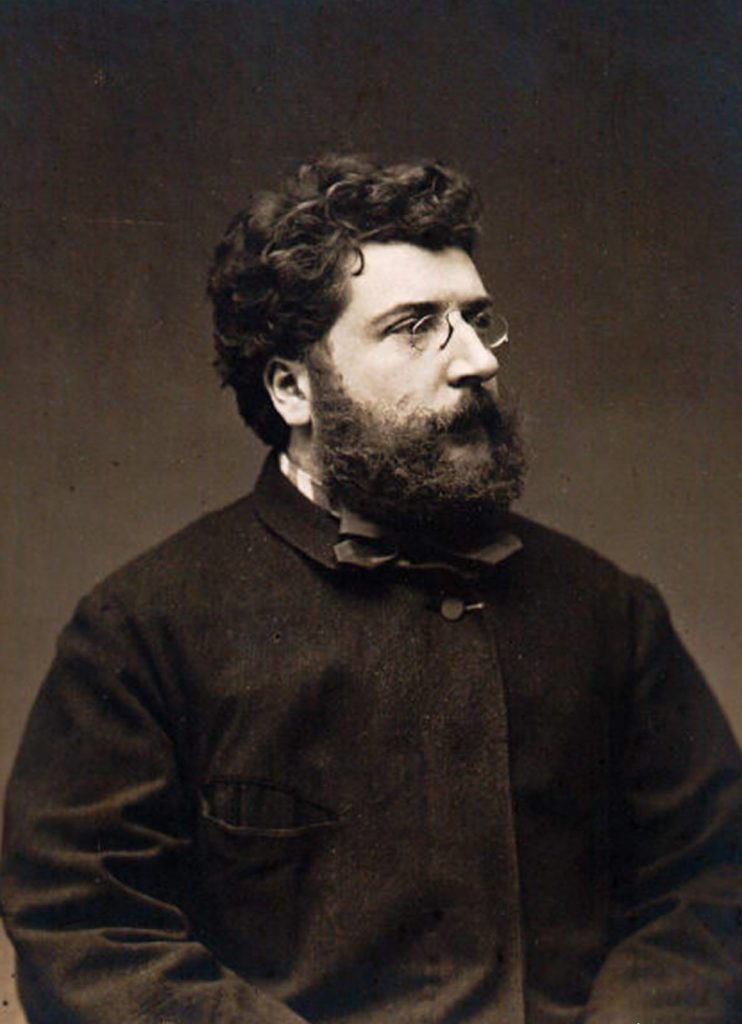

Image: Portrait photograph of Georges Bizet

Please find compelling quotes of Georges Bizet here on his quotes page.

- Georges Bizet: His Life and Works by Douglas Charles Parker (Harper & Brothers, 1926)

- Bizet by Hugh Macdonald (Oxford University Press, 2014)

- Georges Bizet: Carmen by Susan McClary and Richard Wagner (Cambridge University Press, 1992)

- Classical Music: The 50 Greatest Composers and Their 1,000 Greatest Works by Phil G. Goulding (Random House Publishing Group, 2011)

- https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/georges-bizet-397.php

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Georges-Bizet