Early Life of Camille Saint-Saëns: A Young Prodigy

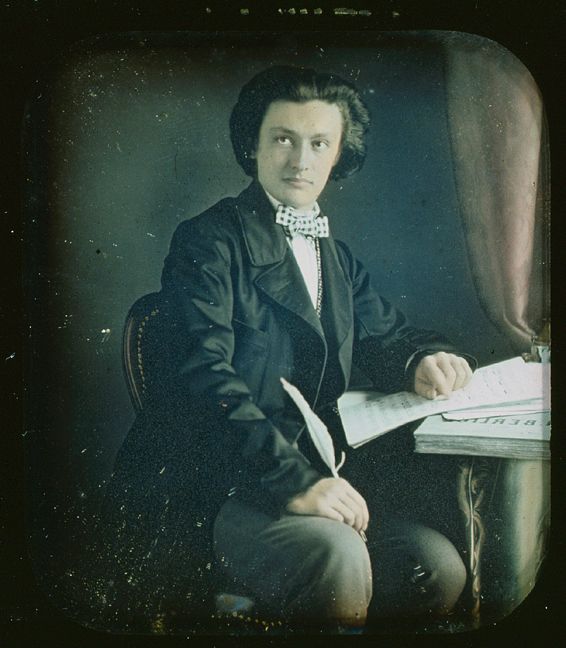

I was born in Paris on October 9, 1835. From a very young age, I displayed inordinate musical talent, debuting at only ten years old at the Salle Pleyel in Paris.

My father died of consumption [tuberculosis] when I was very young, and I was sent away to live with a nurse for two years, because my mother feared I would become infected. When I returned home, I lived with my mother and great-aunt, and it was my great-aunt who taught me the basics of piano when I was two years old.

At seven years old, I became a student of Camille-Marie Stamaty, who had me practice with a bar beneath my forearms so as to concentrate all my movements on my hands. My mother did not want me to become famous at too young an age, often saying to me: “If you work merely to be applauded, you will never do anything worthwhile.”

Image: Photograph of a young Camille Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns and The Paris Conservatory: Award Winning Student

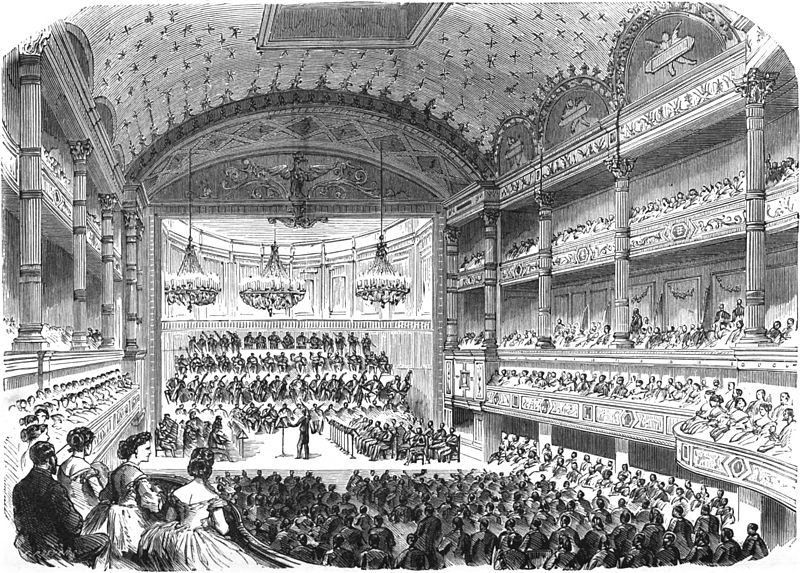

I was later admitted to the Paris Conservatoire in 1848 at thirteen years old. I enjoyed being the wittiest in the class, the funniest, and would often play music that would amuse my classmates in its ridicule. When my mother hosted Monday night soirees, I would often perform by singing operas, exaggerating the female parts and sometimes even convincing friends to join in.

School was something I excelled at in general. Not only was I a young prodigy, I found myself interested in other subjects such as botany, philosophy and astronomy. So much so, that I sometimes wrote scientific articles and spoke with scientists at length about their work.

Historians have written about me at length, but it was Harold C. Schonberg who wrote: “It is not generally realized that he was the most remarkable child prodigy in history, and that includes Mozart.” I dedicated time and effort to my craft, wanting to become the best of the best, and knowing I could achieve it by trying and working harder.

Image: A drawing of a performance in the concert hall of the Paris Conservatory of Music

Camille Saint-Saëns Competitions: The Prix de Rome and Others

In 1851, at sixteen, I won the Conservatoire’s prize for organists and began composition studies, taught by Fromental Halèvy. He was an excellent teacher, and he honed my skill in composition. “The artist who does not feel completely satisfied by elegant lines, by harmonious colors, and by a beautiful succession of chords does not understand the art of music.”

Because of his teachings, I felt ready a year later to compete in the Prix de Rome. I was unsuccessful, but the defeat, this time, did not deter me. I took my talent elsewhere, entering a competition that was organized by the Société Sainte-Cécile.

For the competition, I composed an ode that would then become my Ode a Sainte-Cécile, and won first prize. I would enter to compete in the Prix de Rome one last time in 1864, which shocked and scandalized the public. By then, I was a well-established composer, and over twenty-five years old, and did not need the financial aid or career boost winning the competition would give me.

Once again, I did not win, although it sounded like I should have. One of the judges, Berlioz, later said that he was “sorry” to vote against me, but my competition essentially needed the win more than I. This loss followed my career for years.

Organist Appointments and New Compositions for Camille Saint-Saëns

In 1853, at eighteen, I left the Conservatoire and became an organist at the church of Saint-Merri. The appointment gave me a comfortable income and I was able to concentrate on my own compositions while working, as well. In that time, I composed Symphony in E which won me another prize from the Societe Sainte-Cécile.

At twenty-three years old, in 1858, I left Saint-Merri for an organist post at La Madeleine. Liszt declared me the greatest organist in the world once he heard me play at La Madeleine. It was an important post, playing for the most important and influential church in France.

I enjoyed the works of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt, but did not admire the forwardness of the works or how modern they were. “I admire deeply the works of Richard Wagner in spite of their bizarre character. They are superior and powerful, and that is sufficient for me. But I am not, I have never been, and I shall never be of the Wagnerian religion.”

Image: Photograph of Camille Saint Saëns playing piano while others watch

Camille Saint-Saëns Becomes A Teacher

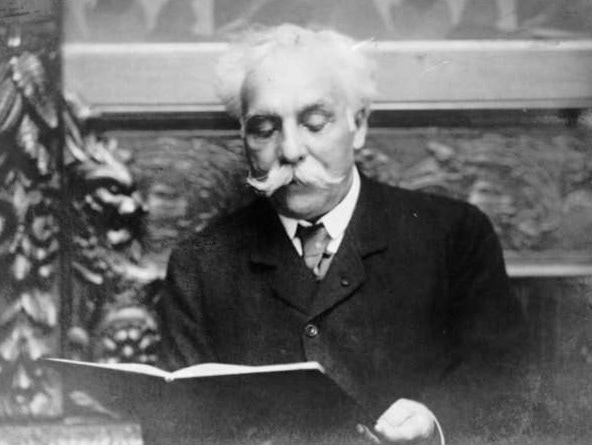

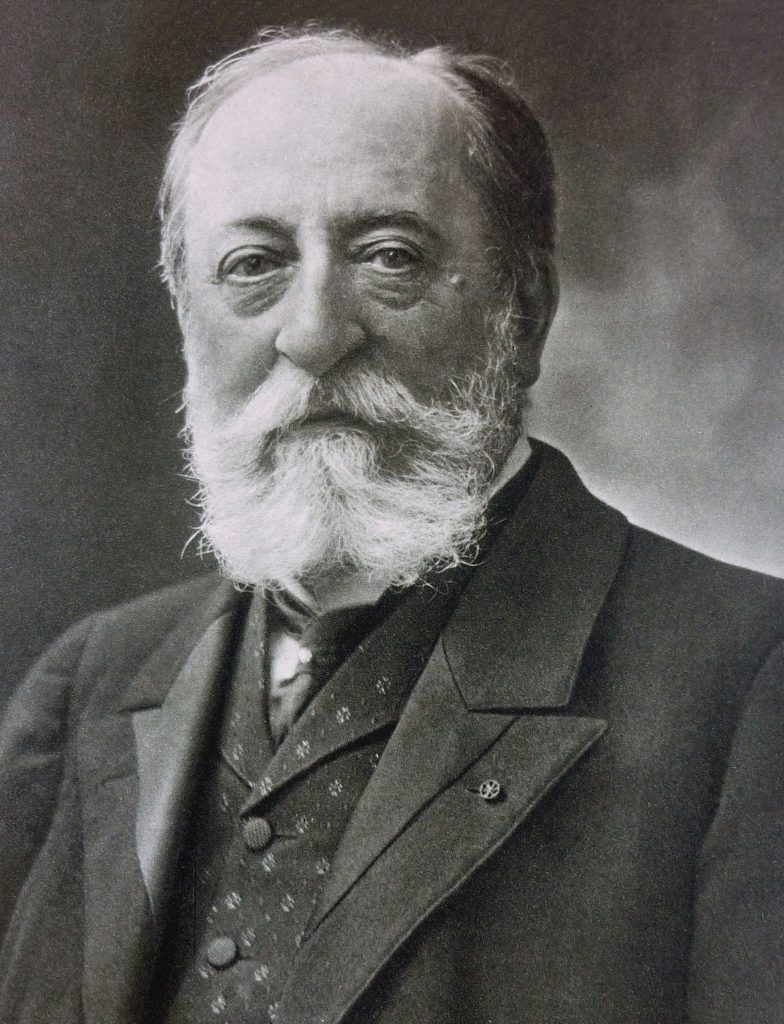

When I was twenty-six, in 1861, I took up a teaching post at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse in Paris. I taught the piano and built a good rapport with my students, some of which went on to become great composers. One was Gabriel Fauré, who also, incidentally, became a very good, lifelong friend of mine.

Teaching opened my eyes to the ability of influencing future composers and musicians. I introduced the students to contemporary music, and even wrote music for them that they then used for their own performances.

In fact, The Carnival of the Animals began with my students in mind, even though it took me twenty years to complete. It was never meant to be more than a bit of fun, a humorous piece, and although I had started it with the intention of having my students perform it, it ended up premiering at a private concert in March 1886, when I was fifty-one.

Image: Photograph of composer Gabriel Faure reading a book

Saint-Saëns’s New Compositions and Last Competition

Apart from The Carnival of the Animals, and especially after my second loss at the Prix de Rome, I struggled to compose while teaching. All of my time and effort went into my work, and there was very little creativity left over. It was not until I left in 1865 that I put pen to paper again, and I began composing again, making up for all the lost time. “I produce music as an apple tree produces apples.”

Two years later, in 1867, Les noces de Prométhée won the composition prize at the Grande Féte Internationale and my Second Piano Concerto gained a permanent place in the repertoire in 1868. I had submitted it as an anonymous entry after working on it diligently. It was by far the biggest piece I had ever worked on, even including notes for a harp accompaniment, an eight-part chorus and even taking care of the parts for wind instruments. Although I’d won, it was not a happy win. There were rumors I had cheated (possibly brought about because I had not revealed my true identity until the end), and some even claimed I had ripped off Wagner and submitted the work as my own.

I won no prize money in the end, and they refused to stage the premier. Many excuses were given, but the one the judges settled on was that the music was not suitable for acoustic — ridiculous, but I made no arguments. Instead, I went to the papers, full of fury, and the judges back down, allowing me to claim my winning money — 2,500 francs.

The francs were the first big prize I had ever won, and the festival would be the last competition I ever entered. It soured my outlook on big competitions showcasing the ‘best’ composers and musicians.

Image: Photograph of Composer Saint-Saëns playing piano with an orchestra

The War and Its Aftermath for Camille Saint-Saëns

When the Franco-Prussian war broke out, I decided to join the National Guard. I had always been a patriotic citizen of France and could not bear the thought of not doing my part for my country. However, during the Paris Commune, my dear friend and superior at La Madeleine was murdered by rebels, and I suddenly felt unsafe.

I escaped to England, and gave recitals in order to support myself. I’d arrived in the country with no more than 1,000 francs to my name. When the recitals were not enough, I resorted to borrowing money to get by.

Returning to Paris in 1871, at thirty-six years old, I became more and more convinced with my idea of creating a pro-French musical society to stamp out the ever-growing success of German and foreign music. I had started thinking about it before the Franco-Prussian war, but it became increasingly obvious to me that this is what Paris needed, and especially French students: somewhere to showcase their work fairly.

Saint-Saëns’s New Beginnings: The Société Nationale de Musique, Marriage and Family

The idea of the Société Nationale de Musique was to uplift French music, composers and musicians alike. I was the Société’s vice president, and I had co-founded it with Romain Bussine. We had a range of members, including some of my students, and others were close friends. Le Rouet d’Omphale premiered at a concert for the Societe in 1871.

In 1875, I got married to Marie-Laure Truffot. I surprised everyone with the marriage, particularly the drastic age difference between us. In 1875, I was forty years old and Marie-Laure only nineteen. I could not bear the thought of proposing directly to her, and so I sent a note to her brother and asked if he would like to be my brother-in-law.

We lived with my mother in an apartment in Paris, and she did not bless our union or approve of it. My mother and I had always been close, being my only living parent since I was an infant, and so my wife and I decided to move away from her in the hopes of establishing our own life together.

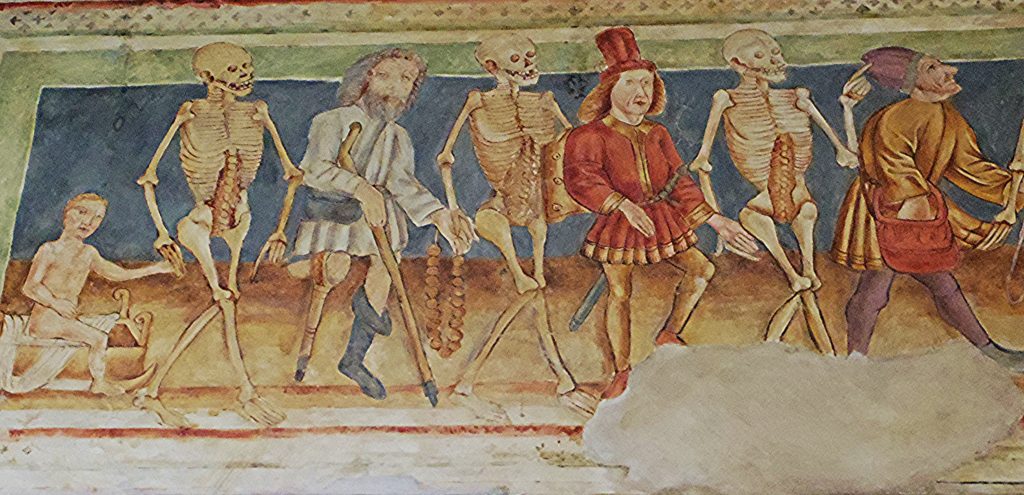

We had two children together, but neither survived through to adulthood. In 1878, my son André, who was two years old, fell out of a window and died, followed six weeks later by my youngest, Jean-François, who died of pneumonia at only six months old. Their deaths wrecked our marriage, and I found it difficult to live with my wife, whom I blamed entirely for the death of André.

It is from then that I began to change, my enthusiasm for music twisting towards something else. I quit my appointment as organist at La Madeleine because religious music was beginning to irritate me; I wanted to expand my work and concentrate on my performances as a soloist in other cities.

The tragedies that had followed me footstep by footstep became the inspiration behind Danse Macabre and Samson et Delila. The former, in particular, I began shortly after the passing of my children.

Image: Painting of the opera Danse Macabre

Camille Saint-Saëns’s Love for Traveling

I began to travel, putting aside the organ. Albert Libon passed away and had left me a large legacy, which I then used to widen my worldview. I traveled to Egypt, which I fell in love with immediately, inspiring me to compose more and more. Egypt and Algeria became frequent destinations for me in the winter months, especially after my mother’s death.

In 1877, when I was forty-two, Samson et Delila premiered in Weimar. I had been working on it since 1867, and it was meant to be a duet, at first. “A young relative of mine had married a charming young man who wrote verse on the side. I realized that he was gifted and had in fact real talent. I asked him to work with me on an oratorio on a biblical subject. ‘An oratorio!’ he said, ‘no, let’s make it an opera!’ and he began to dig through the Bible while I outlined the plan of the work, even sketching scenes, and leaving him only the versification to do. For some reason I began the music with Act 2, and I played it at home to a select audience who could make nothing of it at all.”

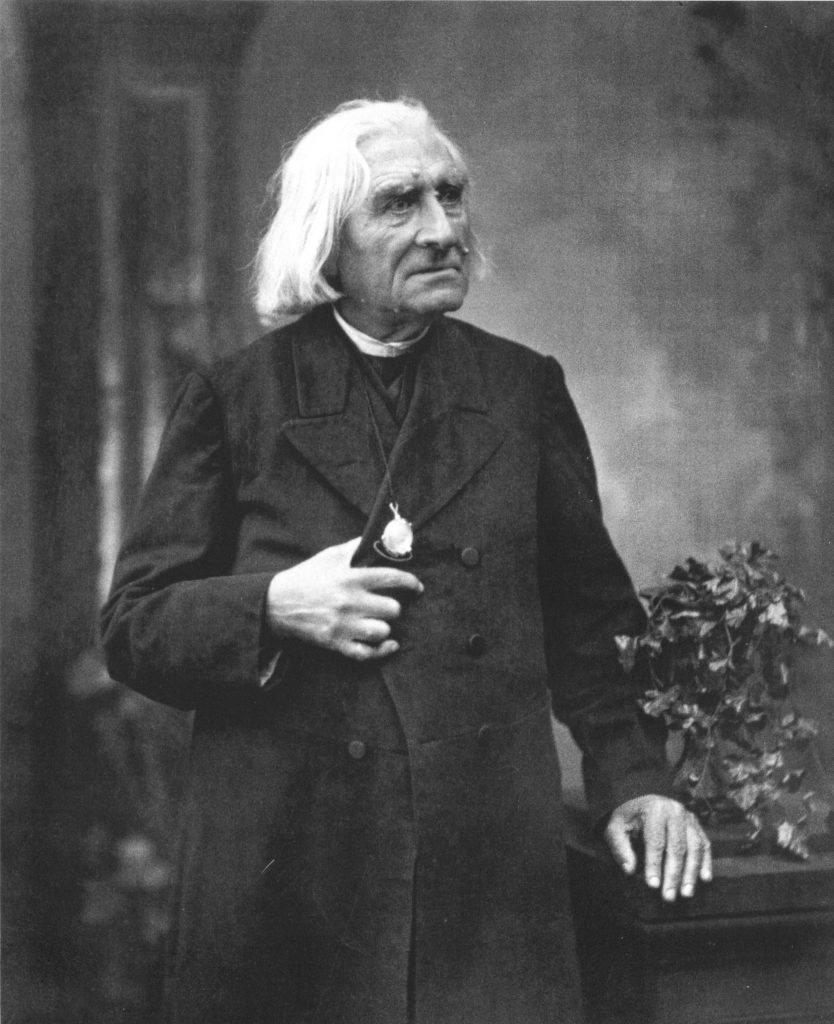

It was thanks to my dear friend Liszt’s power that Samson et Delila premiered on December 2 1877 at the Grossherzogliches Theatre in Germany. Liszt had used his power and influence to persuade the director of the theatre, who owed his own success to Liszt. We translated the work into German, and it was then able to premier at the theatre.

Image: Photograph of composer Franz Liszt

Camille Saint-Saëns’s Bitter Endings

In July 1878, my wife and I visited a spa. I later disappeared, sending her a letter to let her know I would not be returning. Our marriage had been crumbling for years, and I wanted to be done with it. We never officially divorced, and I never remarried. Instead, I found a new family with Gabriel Fauré, his wife and two children.

I suppose the end of my marriage marked the end of my peak in my career. “I like good company, but I like hard work still better.” I had struggled for years to make it big, and the early 1880s brought me more struggle as I tried to find success at opera houses. I staged Henry VIII in 1883 at the request of the Paris Opera, and it was successful.

Henry VIII had gone through several changes, at first intended to have comedic characters, it covers the king’s life during his divorce of Catherine of Aragon. I heavily researched the English music from that time, and even borrowed librettos from the Great British Library to help me on my journey. When it premiered successfully, I was relieved.

Image: Drawing of Henry VIII Act 3 at Paris Opera

Patriotism and Its Influence on Camille Saint-Saëns

I resigned as vice presidency of the Société Nationale in 1886, when I was fifty-one. I found I did not agree with their changing views. They wanted to expand away from solely French music and I was worried that German music was becoming too influential. Our clashing ideals could not be settled, and so I made the move and resigned my place.

My patriotism influenced every aspect of my life, but particularly my music and career as a composer. I became openly hostile towards Wagner and his music, and after years of championing him, I could not help but criticize the man. I lost many engagements, received bad reviews in Germany and made some comments I regret towards the composer.

The Philharmonic Society of London commissioned the Third Symphony in 1886. “I gave everything to it I was able to give. What I have here accomplished, I will never achieve again.” It became a history of my career, and I dedicated it to Franz Liszt, who had always been one of my greatest supporters and friends, after his passing. It was received successfully in London and even more greatly in Paris when it premiered in 1887.

Camille Saint-Saëns Mourning, Grief and Depression

My mother died in December of 1888, when I was fifty-three. I became deeply depressed and even suicidal. With these dark thoughts, I retreated to Egypt where I continued to compose operas. I stayed in Algeria to recover from the grief until May 1889 and I kept a log of my travels in a book under the name Sannois, chronicling the places I visited and when. I composed very little in the years I travelled, especially in the early 1890s, but I did perform a concert in Cambridge in 1893 alongside Bruch and Tchaicovsky.

Last Years and Death of Camille Saint-Saëns

Finally, I returned to Paris in 1900, where I bought a flat. Although I still travelled, it was more for business than pleasure, my performances taking me often to Germany and England. In that time, I lost much of my enthusiasm for modernism, and struggled to enjoy Fauré’s new opera Penélope even though it had been dedicated to me. I never told him, though, choosing instead to keep my opinions to myself — for once!

I became out of sorts with the music scene in Paris. The rapid growth and change made me uncomfortable and had me realize that I had no place in the music world any longer. I walked out of the premier for The Rite of Spring in 1913, calling Stravinsky insane. The story involved the sacrifice of a young woman, pagan rites, and it was most definitely a daring creation.

My patriotism became a growing concern for my friends, especially Fauré, when I decided to organise a boycott of German music. I believed France should come first, no matter the outcome, and my boycott was not contested in way, shape or form. I was joined by Vincent d’Indy and Theodore Dubois and roughly around twenty others when we published our manifesto in the press.

We argued that German music should not be upheld during those trying times, and unfortunately other composers found themselves in the firing line, so to speak. Wagner, particularly because of our fraught past, was seen as the symbol of German patriotism. Without the music of German composers, the opera was slow to reopen.

I died of a heart attack on December 16 1921. I had always struggled with my health, always at risk of consumption and struggling with poor eyesight in my later years. Initially, I had been in Paris to give a concert. I was eighty six years old, and a month after the concert I decided to return to Alegria as I normally did in the winter months. The heart attack was sudden and came with no warning.

Later, my body was returned to Paris and I was given a state funeral before being buried at the cemetery of Montparnasse. My wife, Marie-Laure, was said to be there, hidden from the crowd.

Image: Photograph Camille Saint-Saens, Composer

Please find compelling quotes of Camille Saint-Saens here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camille_Saint-Sa%C3%ABns

- Camille Saint-Saens: A Guide to Research by Timothy Flynn (Routledge, 2004)

- Camille Saint-Saens: A Life by Brian Rees (Chatto & Windus, 1999)

- https://www.redlandssymphony.com/pieces/symphony-no-3-organ

- https://www.allmusic.com/artist/camille-saint-sa%C3%ABns-mn0000688311/biography

- Camille Saint-Saens, His Life and Art by Watson Lyle (K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited, 1923)

- Famous Composers by Nathan Haskell Dole

- 50 Famous Composers by Gervase Hughes

- World Great Composers by David Ewen

- Quotes: https://quotes.thefamouspeople.com/camille-saint-sans-5702.php