Maurice Ravel Growing Up and the Beginning of a Musical Life

I was born March 8, 1875, in the Basque town of Ciboure in France, near Biarritz, into a talented family. My father, Pierre-Joseph Ravel, was a clever engineer and manufacturer and while my mother did not work, his fruitful career provided for us all. Their marriage was very happy.

My mother and I were very close and she sang to me often. My earliest memory is of her singing me folk songs as a young boy. “Throughout my childhood, I was sensitive to music.

My father, much better educated in this art than most amateurs are, knew how to develop my taste and to stimulate my enthusiasm at an early age.” I was homeschooled by my father rather than given a more formal education, and I had initially wanted to become an engineer like him before turning to music.

I began piano lessons at seven years old, with Henry Ghys. Henry was a friend of Emmanuel Chabrier, who noted that I was very intelligent, and took to the instrument quite well.

At twelve years old, in 1887, I began studying harmony, counterpoint, and composition with Charles-René. I was a highly musical boy but not a child prodigy by any means. It took me much practice and determination to do what other great composers could without as much thought.

My earliest compositions are from this period, my younger years, including variations on a chorale by Schumann, a single movement of a piano sonata, and variations on a theme by Grieg.

In 1888, at thirteen, I became good friends with Ricardo Viñes. We eventually became lifelong friends, and Viñes became an important link between myself and Spanish music. We both enjoyed music by Wagner and the writings of Edgar Allen Poe.

Maurice Ravel’s First Performance and Discovering Russian Music

In Paris 1889, at fourteen years old, I was one of twenty-four students who played at Salle Erard. It was here that I became awestruck with the new works by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, a Russian musician. His music had a lasting impression on me, and he inspired my future interest in Russian and oriental music.

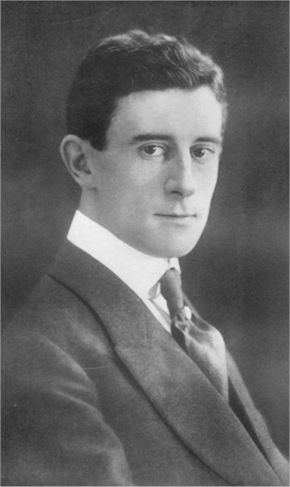

Image: A photograph of a young Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel’s Time at The Conservatoire de Paris

That very same year, I applied for the Conservatoire de Paris after much encouragement from my parents. I passed the admissions exam in November 1889 by playing music by Chopin and I won the first prize in the Conservatoire’s piano competition in 1891.

Sixteen years of age at the time, I did not enjoy learning on a schedule. Music scholar Barbara L. Kelly once wrote that I “was only teachable on his own terms.” She was right. Although I made steady progress in school and class, I was otherwise unspectacular, and the more I was pushed, the less I wanted to work on whichever piece I was composing or learning at the time.

This led to my expulsion in 1895, when I was twenty, after winning no more awards. Although my full works of that time survive to this day, they were composed during my time at the Conservatoire. Sérénade grotesque for piano and Ballade de la Reine mort d’aimer are two of those pieces. I had written Sérénade grotesque as a dedication to my dear friend Viñes and it was inspired by Emmanuel Chabrier himself, and his French romanticism.

My true calling, I learned quickly, was composition, and I had a great ambition for it. My father introduced me to Erik Satie who was a café pianist. I was one of the first musicians to recognize Satie’s originality and talent. I particularly liked how unorthodox his music was, how it didn’t follow the rules I had become accustomed to. His music alone taught me to think outside of the box when composing. He was a great inspiration to me, even considering later incidents between the two of us.

Image: Photograph of Maurice Ravel sitting next to a piano

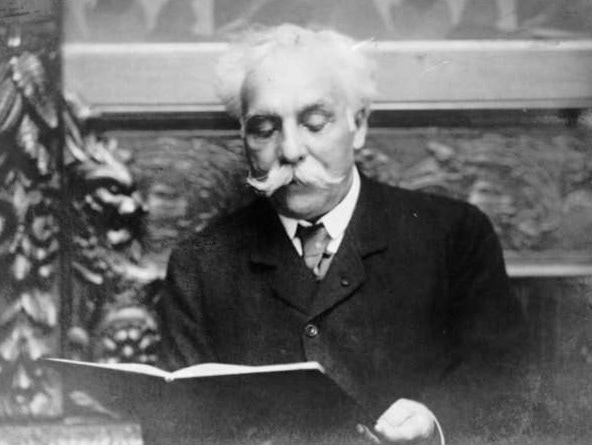

Maurice Ravel Meets Gabriel Fauré and Returns to the Conservatory

My return to the Conservatoire in 1897 began my studies of composition with Gabriel Fauré. Fauré ended up being a major influence on my development as a composer. He reported a “distinct gain in maturity… engaging wealth of imagination.” Fauré helped me challenge my views on music and composition, and the fluidity of the two. Unfortunately, Théodore Dubois was not of the same mind when it came to my talent. Indeed, he openly disliked my progressive outlook on music – as much as he disliked Fauré’s, I have no doubt.

That same year, I conducted my first performance of the Shéhérezade. It received mixed responses from the audience and critics. One said, “a jolting debut: a clumsy plagiarism of the Russian School.” Another called me a “mediocrely gifted debutant… who will perhaps become something if not someone in about ten years, if he works hard.”

In 1899, I composed Pavane pour une infante défunte that had been commissioned by Winnarette Singer, also known as Princesse de Polignac. I would describe the piece as “an evocation of a pavane that a little princess might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court.” I had composed it to be played very slowly, and this did not please critics. One complained that it was almost unbearably slow. Modern interpretations play it faster, and it bothers me. It was not how I had intended it to be played.

Finally, under Fauré’s guidance, I wrote Shéhérezade and a violin sonata. However, those two pieces did not win any prizes, and I was expelled again from the Conservatory in 1900.

Image: Photograph of composer Gabriel Faure reading a book

Les Apaches and Marice Ravel

We formed Les Apaches (or “The Hooligans”) that same year. The name was given by Viñes to represent our status as “artistic outcasts.” The idea was to create a group of people and give ourselves the freedom to discuss music, musicians and the like freely.

The group met regularly and we stimulated each other intellectually by exchanging opinions and debating. Debussy’s music was often discussed among us, and Debussy and I became friends. Our friendship lasted over ten years, but it was never close. I think we were mostly great admirers of each others’ music, but saw each other as rivals, as obstacles to be overcome.

Image: Photograph of some of “Les Apaches,” Léon-Paul Fargue, Maurice Ravel, Georges Auric, Paul Morand

Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy: A Rickety Friendship and Unwanted Labels

It was my friendship with Debussy that gave me the label “impressionist composer.” Mine and Debussy’s works were often taken as part of a single composer, or part of the same genre.

I believed Debussy was an impressionist, but I disliked the label used on myself. Debussy’s “…genius was obviously one of great individuality, creating its own laws, constantly in evolution, expressing itself freely, yet always faithful to French tradition. For Debussy, the musician and the man, I have had profound admiration, but by nature I am different from Debussy… I think I have always personally followed a direction opposed to that of symbolism.”

During the first years of the 1900s, I composed a piano piece named Jeux d’eau (1901), and the orchestral song cycle of Shéhérazade (1903). Debussy and I ended our friendship shortly after when tension began to grow about our professional careers.

People formed sides, and disputes arose about who composed what when and who influenced whom. Strongly campaigning on the anti-Ravel team was Pierre Lalo, a French music critic. I remember he once wrote, “Where M. Debussy is all sensitivity, M. Ravel is all insensitivity, borrowing without hesitation not only the technique but the sensitivity of other people.”

When our friendship ended, I said, “It’s probably better for us, after all, to be on frigid terms for illogical reasons.” However, I know the rift may have been caused by myself and Misia Edwards, my close friend, and Lucienne Bréval. We financially helped Lilly Debussy, his ex-wife, when he left her to go live with Emma Bardac in 1904.

Perhaps it had been the wrong thing to do, because I’d heard rumors that this had rankled him. I had waited for a confrontation, but we never spoke about it. It did not help the growing rift between us, though. If anything, it added fuel to the fire.

Image: Photograph of Claude Debussy

Maurice Ravel and The Prix de Rome and an Unexpected Scandal

As most composers have, I tried to win the most prestigious award for young composers in France— the Prix de Rome. Debussy had been a past winner, along with Berlioz and Massenet.

It had been a very stressful competition, one where I was knocked down a few times. In 1900, I was eliminated in the first round. In 1901, I won second prize. In 1902 and 1903, I didn’t get through to even the first round. I know Paul Landormy, the musicologist, has had his suspicions about this. He even said that the “judges suspected” I was “making a mockery of them by submitting academic cantatas.” It felt like whatever I tried, I was not good enough for the judges of the Prix de Rome.

I was not willing to quit trying, though. In 1905, at age thirty, I tried again, competing for the last time. I did not know at the time that this last try would cause a national scandal, but it did. I was unjustifiably eliminated — unjustifiably enough that even Lalo agreed, which is surprising on its own — in the first round.

The press had a field day when it was found out that a professor at the Conservatoire was on the judges’ panel, and only his students were picked for the final round. His name was Charles Lenepvue and his belief that this was merely a coincidence only added fuel to that fire.

The scandal was dubbed ‘L’ affair Ravel’ and ultimately led to the resignation of Théodore Dubois, who was the Conservatoire’s director at the time. Gabriel Fauré would later take his place, revolutionizing the Conservatoire completely.

Following the scandal, Misia and her husband Alfred (who was the owner and editor of Le Matin, the same paper Pierre Lalo wrote for) took me on a seven-week cruise in June and July of 1905. It was the first time I had been abroad, and it was a much-needed break after the stress of my last attempt at the competition.

Maurice Ravel Finds New Patterns

By the later part of the first decade of the 1900s, I fell into a pattern of writing pieces for piano and then reworking them for orchestra. Reworking piano pieces enabled me to increase the number of pieces published and performed. I was indifferent to financial matters — composition was never about money to me, but about the art itself.

Some of the pieces that were reworked for orchestra included Pavane pour one infante défunte (1910), One barque sue l’océan (1906, originally from the 1905 piano suite Miroirs), the Habanera section of Rapsodie espagnole (1907-08) and Ma mère l’Oye (1911).

Maurice Ravel Passes on the Knowledge

I gave some lessons to people I thought would benefit from them, but I was in no way a professor or a teacher. One student, Manuel Rosenthal, later said that I was a very demanding teacher when I thought a pupil had talent, and it’s true. I took a leaf out of Fauré’s book and pushed students to find their own voices, reminding them that they shouldn’t be overly influenced by outside sources. I warned Rosenthal against learning from Debussy’s music. I said, “Only Debussy could have written it and made it sound like only Debussy can sound.”

Image: Photograph of Maurice Ravel at the piano writing music

George Gershwin once asked me for lessons when he was staying in Paris. I had to turn him down, worrying that studying classical music too in-depth would ruin his music, which was heavily influenced by jazz. He would not have benefited from any lessons with me.

My most known pupil was composer Ralph Vaughan Williamses. He said I helped him escape from “the heavy contrapuntal Teutonic manner.” My motto was complexe mais pas compliqué, Williamses went on to say: “He showed me how to orchestrate in points of color rather than in lines. It was an invigorating experience to find all artistic problems looked at from what was to me an entirely new angle.” I always tried to teach my pupils to think outside the box, to challenge what they thought to be the norm when it came to music.

Maurice Ravel On Marriage and Children

My private life was always my best kept secret. I never married, which was the source of much gossip and speculation. Some said I was in love with Misia Edwards, and others claimed I was homosexual. It’s all speculation. I have always thought I was not made for marriage. I was an artist, and that is what I dedicated my life to. One thing I will confirm was that, although I had none of my own, I loved children and enjoyed their company. A few of my pieces are in honor of my friends’ children, and I often included them in the first performances.

Maurice Ravel Visits London and Sets Up the Société Musical Indépendente

In 1909, at thirty-four, I had my first concert outside of France. I visited London as a guest of Vaughan Williamses and performed at the Société des Concerts Français. The reviews were favorable, but nothing more came of it.

A year after my London concert, in 1910, I, along with other ex-pupils of Fauré, set up the Société Musicale Indépendante and made Fauré president of the new organization. The opening concert was held on April 20, 1910, and I played Debussy’s work, a piano suite named D’un cahier d’esquisses. The idea was to support the creations of modern contemporary music, making it easier for musicians and composers alike to feel free of the restrictions Société National de Musique had set in place.

Maurice Ravel New Premieres and Ballets

L’heure espagnole premiered in 1911, when I was thirty-six years old. It was the first of my two operas and had been completed in 1907. The manager of Opéra-Comique had worried that its plot would be offensive to the women in the audience. When it premiered, it was only modestly successful. It later became popular in the 1920s.

Image: Painting of Daphnis et Chloé Set Act II 1912 ballet

It was in 1912 that three of my ballets premiered. One was Ma Mère l’Oye, the orchestrated version. It was highly well received. Indeed, it was described by The Times “the enchantment of the work… the effect of mirage, by which something quite real seems to float on nothing.” It quickly toured, first played at the Queen’s Hall in London only weeks after its Paris premiere, and it was then performed again at the Proms the same year. It was one of my most successful endeavours.

The second was Adélaïde ou le langage des fleurs, which opened at the Châtelet in April 1912. And the third was Daphnis et Chloé.

Daphnis et Chloé was a particularly interesting, but stressful project. It was commissioned by the impresario Sergi Diaghilev for his company, the Ballets Russes. I had worked closely with the choreographer, Michael Forkine. His modern approach to dance pleased the modernist in me, but we did not see eye to eye very often and many disagreements occurred.

In the end, the work was completed late and it premiered under-rehearsed. The reception was unenthusiastic and lukewarm, and the stress and effort of completing it made me very ill with neurasthenia. It meant that after the premiere, I had to rest for several months. A year later, the ballet was revived in Monte Carlo and London.

I composed very little the following year. I was thirty-eight and feeling a lull in my career, although I did collaborate with Stravinsky on a performing version of Mussorgsky’s unfinished opera Khovanshcina. I also finished Trois poèms de Mallarmé for soprano and chamber ensemble and two short piano pieces. It was a creatively difficult time to try and begin anything new, and so I made sure to concentrate on pieces that needed to be finished, or needed my attention the most.

That same year I had the pleasure to be present at the dress rehearsal of The Rite of Spring along with Debussy. It was truly phenomenal, and I had predicted that the premiere would be as great as Fauré’s Pelléas et Mélisande. I was correct. It impacted the history of music greatly.

The First World War and the After Effects for Maurice Ravel

In 1914, Germany invaded France. I tried to join the French Air Force at first, but I was rejected because of my age and a small heart problem. I composed Trois Chansons for a cappella choir and dedicated them to the people who might have helped me enlist.

Finally, I was accepted to join the Thirteenth Artillery Regiment as a lorry driver in March 1915. By this time, I was forty years old and some said I should not have had to join because of my age. Stravinsky was one who admired my bravery, and he said that at my age and with my name, I could have had an easier place, or done nothing. I felt like I needed to do my part for France, though.

Image: Photograph of Maurice Ravel dressed in a fur with his soldier uniform on in WWI

My time in the army was far from easy. I drove munitions under the cover of night during heavy German bombardment, suffered from insomnia, digestive problems and frostbite on both my feet. My mother’s ill health also weighed heavily on me. The digestive problems led to bowel surgery in the September of 1916.

The Ligue Nationale Pour La Défense de la Musique Française and Maurice Ravel

At the time of the war, Saint-Saëns, Dubois, and d’Indy formed the Ligue Nationale pour la Défense de la Musique Française. I declined their invitation to join. “It would be dangerous for French composers to ignore systematically the productions of their foreign colleagues, and thus form themselves into a sort of national coterie: our musical art, which is so rich at the present time, would soon degenerate, becoming isolated in banal formulas.”

The league, which was campaigning for the ban on contemporary German music, responded by banning my music from their concerts.

Heartbreak for Maurice Ravel

My mother died in January 1917. Her death floored me, and I became terribly depressed. Her passing, coupled with the lingering ill-feelings from my experiences in the war sent me into a spiral of despair. I composed very little during those years. I was only able to complete Le tombeau de couperin. Each movement of the suite is dedicated to a friend I lost in the war.

After the war, my mental and physical stamina suffered greatly and seriously depleted. My output, as a consequence, suffered considerably. Even so, after Debussy passed in 1918, I was seen as the leading French composer of the era. Fauré wrote to me one day, expressing his pride by saying, “I am happier than you can imagine about the solid position which you occupy and which you have acquired so brilliantly and so rapidly. It is a source of joy and pride for your old professor.”

I was offered the Legion of Honor when I was forty-five in 1920. I refused. The French government failed me by telling my mother about my joining the war at the front. I believe this was the cause for her sudden ill-health, and consequently her death. “That was something I couldn’t forgive and it’s why I refused the distinction.”

Erik Satie turned against me, then, and said, “Ravel refuses the Légion d’honneur, but all his music accepts it.” Despite this, I still admired the musician and defended Les Six, Satie’s proteges, from journalistic attacks and I tried to promote their music to the best of my abilities.

The 1920s: Maurice Ravel Falling in Love with Jazz

In 1920, I also completed La valse. It was a commission in response to Diaghilev. I worked on it on and off for a few years, and when I finished it, Diaghilev rejected the piece, stating: “It’s a masterpiece, but it’s not a ballet. It’s the portrait of a ballet.” A permanent rift grew between us then, and we never worked together again.

Image: Photograph of Maurice Ravel playing piano with others posed behind him

In the post-war era, there was a reaction against large-scale music. I was pro “dépouillement” — essentially, I was pro-minimalizing the pre-war extravaganza that had taken over the music industry. I believe my works from that era reflect that, as well as my love for jazz. I preferred jazz to the grand opera and was influenced by the music. Jazz was popular in Paris at the time.

Some of my major works in the 1920s include Chansons Madécasses (1926), an orchestral arrangement of Mussorgsky’s piano suite “Pictures at an Exhibition” from 1922, and the opera L’enfant et les sortilèges (1926).

Maurice Ravel Leaves the City and Tours the World

I retired to the countryside in May 1921 at a small house called Le Belvédère. Alone except for my housekeeper, Madame Revelot, I lived there the rest of my life. Some said I lived like a recluse, because I was either gardening or composing, all alone in my home outside of Paris. In truth, there was nothing I had wanted more than to garden and compose in peace.

Still, even while living as a ‘recluse’, I toured a lot in the 1920s with concerts in Britain, Denmark, Italy and the United States. I had a four-month tour of North America, where I was guaranteed at least $10,000 and an endless supply of cigarettes. The reception I received in North America was so vastly different than the reception I would normally receive in France. Once, the audience even stood up and clapped loudly as I took my seat. I had to comment, “You know, this doesn’t happen to me in Paris.”

Maurice Ravel’s Boléro and Piano Concertos

My last composition of the 1920s was Boléro. Somehow, it became my most famous. I had decided to “experiment in a very special and limited direction…” I had wanted to create “a piece lasting seventeen minutes and consisting wholly of orchestral tissue without music.” It was “one long, very gradual crescendo. There are no contrasts, and there is practically no invention except the plan and the manner of the execution. The themes are altogether impersonal.”

Imagine my dismay when it became my most successful piece. When one elderly audience member shouted “Rubbish!” I even agreed with her, and said, “That old lady got the message!” I once told Arthur Honegger, a member of Les Six, “I’ve written only one masterpiece — Boléro. Unfortunately, there’s no music in it.” It seemed ridiculous to me that the piece I had composed almost on a whim was the piece that would give my career a much needed boost.

I completed the Piano Concerto in D major for the Left Hand between 1929 and 1930. It was a piece commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, an Austrian pianist who had lost his right arm during the war. He was fascinated by the piece, but at first, he had been disappointed. Wittgenstein premiered it in Vienna in January 1932, and then with myself in Paris in 1933.

The Piano Concerto in G Major was completed a year after in 1931.

Maurice Ravel’s Life Altering Accident

The life altering accident happened in October 1932. It was a terrible car accident in which I suffered a head injury. At first, it did not seem to affect me any differently. My close friends had worried since as early as 1927 about my absentmindedness, but within a year of the accident, my symptoms had worsened. It was likely I suffered from aphasia. It affects the brain after trauma, and it is hard to retain coherent thought, and it was difficult to comprehend and formulate language.

Image: Photograph of Composer, Maurice Ravel

Before the accident, I had been composing music for the 1933 film Don Quixote, but unfortunately, I could not keep to the schedule. I ended up finishing three songs over three years for the film which were later published as Don Quichotte à Dulcinée. Those songs were my very last compositions.

The life altering accident happened in October 1932. It was a terrible car accident in which I suffered a head injury. At first, it did not seem to affect me any differently. My close friends had worried since as early as 1927 about my absentmindedness, but within a year of the accident, my symptoms had worsened. It was likely I suffered from aphasia. It affects the brain after trauma, and it is hard to retain coherent thought, and it was difficult to comprehend and formulate language.

Maurice Ravel’s Death and Legacy

The years after the accident, I suffered greatly. I began to forget how to write and spell, and my housekeeper would pin my home address inside my coat in case I forgot. I found myself losing memories quicker than ever neurosurgeons were struggling to find a reason behind this sudden change.

It was my brother, Edouard, that had decided surgery may have been in my best interest. Some doctors believed there might have been a hidden tumour and so, in 1937, I had brain surgery in the hopes of alleviating some of the pain caused by my symptoms.

The tumour which would have explained the discomfort, pain, and memory loss was not found. There was a slight improvement after the surgery, but it did not last long. I quickly slipped into a coma and died on December 28 1937, at 62 years old.

I was interred next to my parents on December 30 1937, at Levallois-Perret cemetery in Paris. I was an atheist, and so no religious ceremony was held. Edouard, my brother, turned my home into a museum, making no changes to it. It is still open to the public today.

Please find compelling quotes of Maurice Ravel here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- Maurice Ravel: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice_Ravel

- The Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers: Ravel by James Burnett (Omnibus Press, 2011)

- Ravel by Roger Nichols (Yale University Press, 2011)

- Proof Through the Night: Music and the Great War by Glenn Watkins, Professor of Music (University of California Press, 2003)

- Ravel: Man and Musician by Arbie Orenstein (Courier Corporation, 1991)

- The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music by Robert Philip (Yale University Press, 2018)

- Ravel: 1875-1937 by Christine Souillard (Editions Jean-paul Gisserot, 1998)

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Impressionism: https://www.britannica.com/art/Impressionism-music