Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Early Years

I was born on September 25, 1683, in Dijon, France. The seventh of eleven children, I was exposed to music at a young age, learning both keyboards and violin.

Father was an organist who spent much of his career playing in several churches around our hometown. Family members persistently promoted learning music in my family, and I became fluent in the language of music before reading or writing learning occurred.

At my school, Jesuit in Godrans, I was well known for disrupting class with my singing, and I believed that my love for opera began during those early educational years. My father must have provided me with a reasonably good musical education as no real formal training in music was received other than what my father taught me.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Years in Milan as an Organist & Violinist

In pursuit of a musical career, I took a trip to Milan alone at eighteen years of age. I followed in my father’s footsteps by securing appointments as an organist for several churches.

Although my time in Italy taught me much, that country did not keep me long. At age 20, shortly after returning to France in 1702, I became a violinist for a traveling company.

Fairly quickly, though, I realized the organ was the instrument I wanted to make a career with, and when I was offered an organ position in the Clermont-Ferrand region in France, in the center of the country. It was easy to accept.

Rameau’s Goes to Paris, Studies & Begins Writing Music

In 1705, at the age of twenty-two, I moved to Paris. There, I met Louis Marchand, an incredibly talented keyboard player, and ended up learning from him as his student.

During this time, I began composing my own pieces, mainly for harpsichord, along with a few cantatas. I leaned heavily on Marchand’s talent in my first published book Pieces de Clavecin, emulating how he enhanced the harpsichord’s natural sound. It was the first of an eventual trilogy, with all three written specifically for the harpsichord.

I demonstrated my interest and talent in instrumental music in books like Le rappel des Oiseaux and La Poule for piano. My instrumental music later influenced composers such as Louis-Claude Daquin and Jacques Duphly.

Jean-Philippe Rameau Returns to Dijon

Four years after my move to Paris, I returned to my hometown of Dijon to take up my father’s mantle as an organist at the Dijon Cathedral. The work was uninspiring, though, and I found myself flitting from church to church, trying to find the perfect place.

After a few years in Lyons and Claremont-Ferrand, and using my experience as a prolific composer coming into my talents, I published a book on musical theory titled Le Traite de l’harmonie. I still had no formal education in music at that point.

Jean-Philippe Rameau Returns to Paris

I later returned to Paris in 1723. It was at that time I began to write stage music when Alexis Piron approached me. He asked me to write music for his comedies.

I wrote four musical tragedies based on Alexis Piron’s stage writing. They included:

1. Samson

2. Linus

3. Les courses de Tempe

4. Lisis et Delie

Although I later reused some of the music for other projects, most of the tragedies never made it to the stage, primarily due to censorship, as in Samson’s case.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Lost Operas & Librettos of Voltaire

Among my lost operas were also pieces composed for librettos by Voltaire. In 1727, I accepted a post as music master for Le Riche de la Poupliniere. Encouraged to write operas and concentrate on composing, Poupliniere introduced me to Voltaire, hoping that our talents combined would create memorable, historical music.

Unfortunately, I struggled to find inspiration in Voltaire’s librettos. After the failure of Samson, Voltaire wrote, “As far as opera is concerned, after the still-birth of Samson, there is no indication that I might wish to write another. The labor pains of the first have scarred me too deeply.”

Despite Voltaire’s declaration that he was finished with operas, shortly afterward, he began work on the libretto of Pandore and enlisted me to help. However, I found this opera work hard to finish, as the storyline lost interest after the first act and left me very little energy to continue writing the music for Pandore. The score was left unfinished.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Marriage and Family

On February 25, 1726, I married Marie-Louise Mangot. She came from a musical family but did not sing professionally. She did sing in my operas. A few years after we married, she performed in Hippolyte et Aricie and Castor et Pollux. We had four children together, two sons and two daughters, and I cared for them greatly.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Opera, Hippolyte et Aricie

Once my collaboration with Voltaire seemed to come to a standstill, Poupliniere organized for the Abbe Pellegrin to provide me with a text based on Phedre-Hippolyte Aricie in 1732. Hippolyte et Aricie came naturally to me.

“I have been a follower of the stage since I was twelve years old. I only began work on an opera when I was fifty; I still didn’t think I was capable; I tried my hand, I was lucky, I continued.”

Little did I know that its first performance at the Opera on October 1, 1733, would catapult my career. The audience’s reception was split: one side was filled with admiration for such innovative work, while the other saw it as a personal attack on traditional French music.

Due to the controversy, Hippolyte failed, especially when Jean-Baptiste Lully’s followers began claiming it went against all of Lully’s ideals and beliefs. His followers were worried I would replace Lully as France’s favorite composer of the time, or so it was rumored. I was not discouraged by the lack of Hippolyte’s commercial success.

Rameau’s Work Challenging Lully’s Ideals

With Poupliniere’s financial support and trust, I came into my own as a composer of operas. Lully had invented tragedie en musique, (tragedy in music), and Hippolyte challenged his ideas for how music tragedy could sound.

Sophie Bouissou, a historian, wrote, “With a single stroke Rameau destroyed everything Lully had spent years in constructing: the proud, chauvinistic and complacent union of the French around one and the same cultural object, the offspring of his and Quinault’s genius.

Then suddenly the Ramelian aesthetic played havoc with the confidence of the French in their patrimony, assaulted their national opera that they hoped was unchangeable.”

In response to the rumors and the debate, I said, “I sought to imitate Lully, not as a servile copyist but in taking, like him, nature herself — so beautiful and so simple — as a model.” The controversy lifted my popularity in the public eye.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Opera, Les Indes Galantes

My second opera was Les Indes Galantes, which I composed purely for public entertainment. The libretto by Louis Fuzelier tells the story of the Grand Vizier Topal Osman Pasha: “who was so well known for his extreme generosity.”

[It] “was based on a story published in the Mercure de Suisse in September 1734 concerning a Marseillais merchant, Vincent Arniaud, who saved a young Ottoman notable from slavery in Malta, and the unstinting gratitude and generosity returned by this young man, who later became Grand Vizier Topal Osman Pasha.”

Les Indes Galantes met a not-so-favorable reception on August 23, 1735 at the Academie Royal de Musique. Even though it ran for twenty-eight performances, I pulled it and chose to revise it. When it debuted again less than six months later, it received a more enthusiastic reception.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Opera, Castor et Pollux

A year after Les Indes Galantes, I composed Castor et Pollux to the libretto by Pierre-Joseph-Justin Bernard. I used some of the music discarded from the unsuccessful Samson, and it became my third opera in the tragedie en musique genre.

It premiered in 1737, in the middle of the roiling controversy surrounding Hippolyte et Aricie, boosting the popularity of Castor’s premiere.

Diderot, a supporter of mine (who later took his support elsewhere), said, “Old Lully is simple, natural, even, too even sometimes, and this is a defect. Young Rameau is singular, brilliant, complex, learned, too learned sometimes; but this is perhaps a defect on the listeners.”

Castor et Pollux was successful. It was seen, later, as my best work.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Opera Dardanus

At a time where Lully’s supporters seemed to become more and more enraged and offended at my work, I was surprised when the Opera asked me to produce some music for an opera called Dardanus.

Based on the libretto by Charles-Antoine Leclerc de La Bruere, it was a lengthy opera that critics enjoyed attacking for seemingly no other reason than its length, claiming it became too convoluted and shoddy as it went on.

Within five months, I had finished the music, and it premiered on November 19, 1739. Seats sold out eight days before the premiere, and despite the Lullists best efforts to dishonor my name and work, Dardanus became an incredible success.

Cuthbert Girdlestone said, “From the extreme dreaminess of the original Act IV, the tragic lament of Iphise and… of Dardanus on the one hand, to the martial or demoniac power of the duet of Act I, the magician’s chorus, the fury chorus, ‘Dardanus gemit’ and… ‘Le despoir et la rage,’ in Act III… there runs a tremendous range of feeling and all points along the scale are marked by first-rate music.”

I later revised Dardanus in 1744, rewriting the last three acts and adding simplicity to the story. The revised version premiered in Paris on April 23, 1744.

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Collaborations & Commissions

1745 marked a turning point in my career. The Royal Court commissioned me to compose celebratory music for victory battles or marriages due to my newfound popularity.

Platee was a comedic opera based on the libretto by Adrian-Joseph Le Valois d’Orville. It was my first attempt at comedy and commissioned for the wedding of Prince Louis and Maria Theresa of Spain. It premiered at Versailles on March 31, 1745, to a great reception.

La Princesse de Navarre was composed alongside Voltaire and commissioned for the wedding, too. Although Voltaire believed the commission was not good enough for me, I wrote the music, which was well-received.

Voltaire, however, said, “Poor Rameau is mad… Rameau is as great an eccentric as he is a musician.” He had many complaints about our collaboration, including, “the ceiling was so high that the actors appeared pygmies and they couldn’t be heard.” After the work became a huge success, Voltaire fell silent.

Jean-Philippe Rameau & the Quarrel of the Comic Actors – Le Guerre des Bouffons

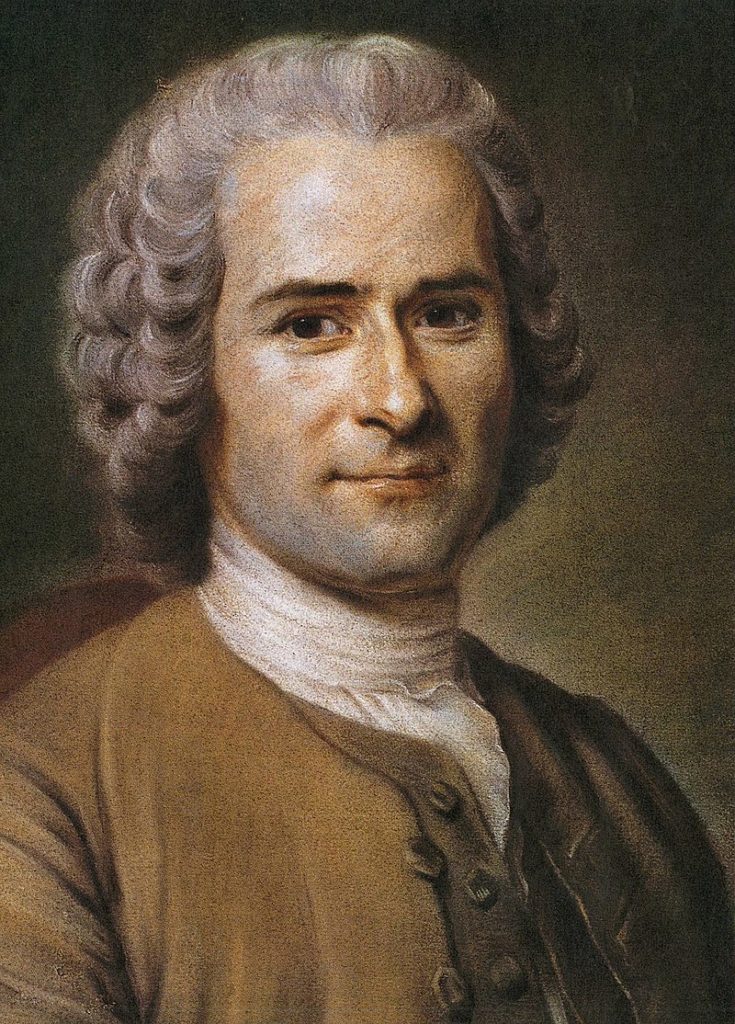

Soon after the successes of 1745 came an extensive argument with the critic Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The resounding success of my tragedies came under attack when Rousseau staged, with an Italian company, La Serva Padrona.

Although it was successful in its own right, Melchior Grimm, along with Denis Diderot and Baron d’Holbach, found a great offense that La Serva Padrona did not topple my tragedies-lyriques from their pedestal.

“If I were twenty years younger, I would go to Italy, and take Pergolesi for my model, abandon something of my harmony and devote myself to attaining truth of declamation, which should be the sole guide of musicians. But after sixty-one [I] cannot change; experience points plainly enough to best course, but the mind refuses to obey.”

This quarrel was later named le guerre des bouffons. I won that fight, just like I had against the Lullists.

The Illness and Death of Jean-Philippe Rameau

After the quarrel, I confined myself to home. I wrote two more operas in that time and other smaller pieces but began to struggle.

“The imagination is worn out in my old head, it’s not wise at this age wanting to practice arts that are nothing but imagination.”

Unfortunately, I became unwell with typhoid fever and died shortly after on September 12, 1764.

My last words were, “What the devil do you mean to sing to me, priest? You are out of tune.”

I was buried at St. Eustache in Paris the same day I passed, and although my burial site remains a secret, a bronze bust atop a tombstone marks a likely spot.

Please find compelling quotes of Jean-Philippe Rameau here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- Great Composers 1300-1900 by David Ewen

- The Rameau Compendium by Graham Sadler: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt6wp84n

- Music and Ideology: Rameau, Rousseau, and 1789 by Charles B. Paul: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2708354

- Jean-Phillipe Rameau: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau