Giacomo Puccini’s Early Years: Struggles with School & Musical Growth

I was born in Lucca, Italy, on December 22, 1858, to a musically gifted family. My father, Michele Puccini, was well established in Lucca as part of a ‘musical dynasty’ founded by my great-great-grandfather, the first maestro di cappella at the Cattedrale do San Martino.

By succession, I was fifth in line for the mantle as maestro, but when my father died in 1864, I was too young to take it up, as I was only six years old.

Instead, my mother insisted on giving me and all 7 of my siblings a good education. Around age 9 or 10, I joined the Cattedrale de San Martino as part of the boys’ choir in 1868.

Around the same time, in 1867, my mother signed me up to attend the Seminario di San Michele, but school was not for me. Struggling in class, I was a restless student. The school suspended me on numerous occasions for being too distracted and even absent. To my chagrin, though, I was continually reinstated after my mother argued with the school.

After graduating from the Seminario in 1872, I joined the Instituto Musicale, where my father and grandfather had attended before me. Despite the pressure of family history, the school proved difficult for me to succeed at; I wanted to quit. I often argued with my mother, who insisted I remain enrolled in the school.

It was not until I began studying under Carlo Angeloni’s tutelage that I began to take education seriously. Under his instructions, I began to compose, writing a few pieces for piano in 1875.

Based on his strong recommendation, I took a field trip to Pisa with some friends to watch Aida at the opera house in 1876. The opera was incredibly stimulating and inspiring, and I channeled all those feelings into my new composition, Preludio Sinfonico.

Giacomo Puccini’s Religious Composition for Easter, Vexilla Regis

A family friend hired me to play the piano at the Royal Casino Ridotti in the Bagni di Lucca region. Noblemen eager to gamble frequented the casino, and the spa-town was famous for its weekend retreats.

When the local church’s organist, Dr. Adelson Betti, asked me to write a piece for his churchgoers, I came up with Vexilla Regis. It was based on a religious text and played throughout Easter Week, entertaining the masses of tourists that had come to the Bagni di Lucca.

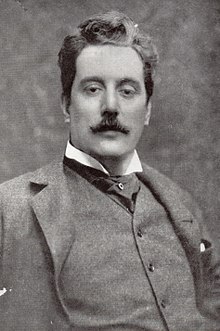

Vexilla Regis was based on the Latin hymn by Venanzio Fortunato; it combined the well-known verses with new music written solely by my hand. After the success of the piece, and the tranquillity I found at the Bagni, I spent a lot of my later adult years in that small spa town, and it was there that I later composed The Girl of the West.

Image: The poster for The Girl of the West, composed by Giacomo Puccini

Puccini Attends the Milan Conservatory, Composing Melanconia & Capriccio Sinfonico

After my studies concluded, my mother insisted I joined the conservatory in Milan. Although I was not keen on the idea of more studies, Queen Margherita’s generous grant, and financial assistance from my uncle Nicholas Ceru, helped sway me to study there. At twenty-two years old, I sat the entrance exam and found it relatively easy. After passing the exam, I was accepted and began lessons. Although this school, like all of the proceeding ones, was still tedious to me, Amilcare Ponchielli encouraged me to compose as a large part of my studies.

Yet, it was not all perfect and sunny days. In fact, at first, it was indeed a struggle to settle in. Homesickness, depression, and a creative block convinced me I needed to drop out. My teacher, Ponchielli, refused to let it happen.

Under his wing, I grew as a composer and musician and, over time, embraced the Milan Conservatory as a place of opportunity for a beginning composer. Channeling my darker feelings about the conservatory, I wrote Melanconia in 1881. “Inspiration is an awakening, a quickening of all man’s faculties, and it is manifested in all high artistic achievements.”

I graduated from the Conservatory on July 16, 1883, with Capriccio Sinfonico as my thesis. It launched my reputation as a respectable and well-liked composer, attracting the attention of journalists and the general public alike. Soon after, I began to feverishly compose, releasing opera after opera with hardly a pause between each new work.

Image: The Milan Conservatory in Paris

Puccini’s 1st Major Opera, The Willis, or The Fairies

The first was The Willis (also known as ‘The Fairies’). Based on Ferdinando Fontana’s libretto, and in turn, based on the short story by Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, it tells the story of the legend of the Vila. It was not an easy feat to accomplish. I had written it for a competition hosted by the publisher of the newspaper ‘Il Teatro Illustrato’ but failed to garner any attention. The newspaper’s reviewers mentioned that I wrote my opera too hastily even to be legible!

The criticism did not deter me. I took The Fairies to some close friends, who funded the production. On the night of its premiere on May 31, 1884, I wrote to my mother: “Theatre packed, immense success; anticipations exceeded; eighteen calls; finale of first act encored thrice.” Shortly after, my relationship with Giulio Ricordi began.

Image: Photograph of Italian editor and musician, Giulio Ricordi

Giacomo Puccini’s Troubled Marriage & Many Affairs

“See, the night doth enfold us! See, all the world lies sleeping!”

In 1884, I met Elvira Gemignani. After the success of The Willis, I had taken to describing myself as “a mighty hunter of wildfowl, operatic librettos, and attractive women.” Elvira had been a former piano student of mine, and unfortunately, she was already married to Narciso Gemignani.

At the time of our affair, Ricordi had secured the financial backing for Edgar’s production (the second opera I had composed). Once the media caught wind of our illicit affair, the production’s financial backers threatened to pull out. Ricordi negotiated with funders, convincing them to continue supporting the opera, but my affair’s damage continued to be problematic.

Although Elvira was married, her friends and family members suggested she leave her husband in favor of me. A letter I received read, “Among other things, it seems to me that, after all that magician Gemignani has put his family through and given his character, she can perfectly well leave him with nothing more than a letter. Goodness me, if he were a saint, and adorable husband—but a character like that!”

As Elvira struggled to get a divorce from her husband, I found myself suddenly tied into another affair with a woman twenty years younger than me. I was so enamored that I bought her a house, and upon discovering the affair, Elvira went on a hunger strike.

My affairs did not end, however. I was caught, with some frequency, in affairs with famous singers. In 1909, Elvira accused a young maid of having sexual encounters with me, and, embarrassed, humiliated, and harassed maid committed suicide after relentless bullying from my wife. When it came to light that it was not true (it was the maid’s sister I had been sleeping with), Elvira faced a jail sentence. Nothing ever came of it, though, and Elvira and I remained married – although unhappily so – even in times of outward harmony.

“Even you, O Princess, in your cold room, watch the stars, that tremble with love and with hope. But my secret is hidden within me, my name no one shall know…”

Image: Photograph of Giacomo Puccini’s wife Elvira and their son

Giacomo Puccini’s Edgar

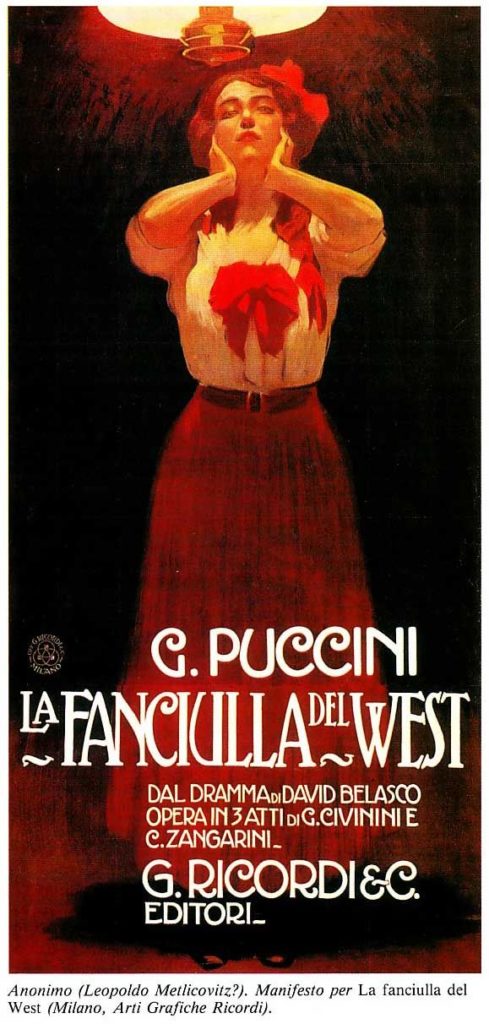

Edgar became the pinnacle on which my career dangled. After Willis’s success, Ricordi commissioned me to write an opera about knights torn between love and lust. Influenced by Wagner’s Tannhauser, it was not well-received at the first premiere. Edgar became the opera I spent years trying to revise and perfect. “It was an organism defective from the dramatic point of view. Its success was ephemeral. Although I knew that I wrote some pages which do me credit, that is not enough — as an opera, it does not exist. The basis of an opera is the subject and its treatment. In setting the libretto of Edgar I have, with all respect to the memory of my friend Fontana, made a blunder. It was more my fault than his.”

Image: Photo of the poster for the opera Edgar, by composer Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini’s Opera, Manon Lescaut

Between 1889 and 1892, I began working on Manon Lescaut. After employing five librettists, I urged them to use the novel by Abbe Prevost as inspiration. Manon became the opera of my heart. Ricordi was utterly against the idea of producing Manon, as this subject had already been successfully written and premiered by Jules Massenet in 1884.

I argued my case at length, saying, “Manon is a heroine I believe in, and therefore she cannot fail to win the hearts of the public. Why shouldn’t there be two operas about Manon? A woman like Manon can have more than one lover. Massenet feels it as a Frenchman, with powder and minuets. I shall feel it as an Italian, with a desperate passion.” My rendition premiered in Turin on February 1, 1893, to resounding success!

Image: The poster for the opera Manon Lescaut, by Puccini

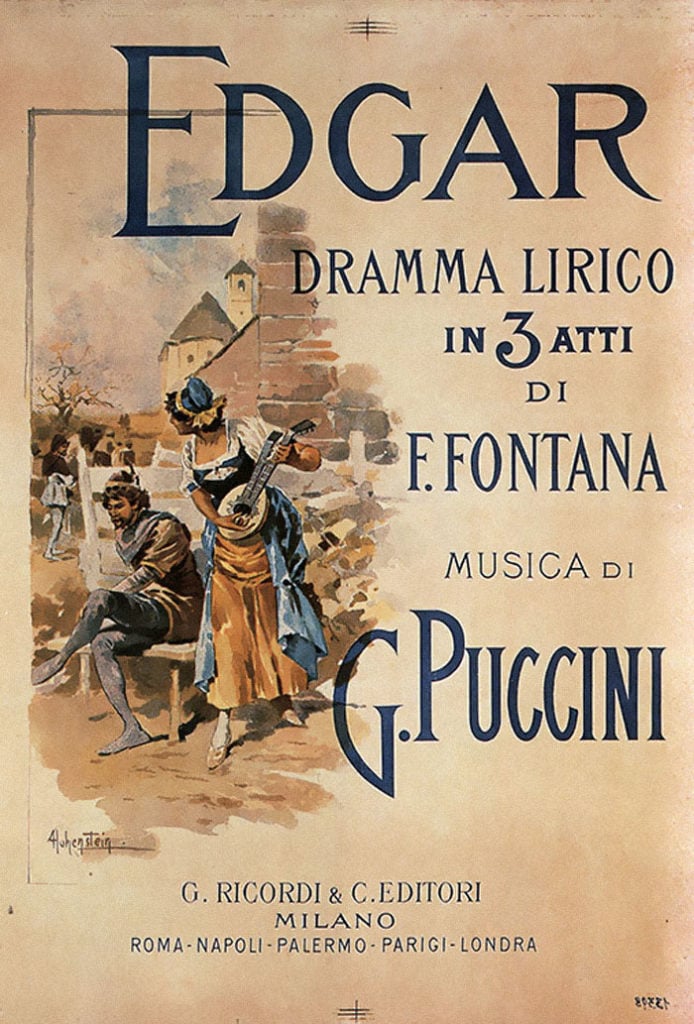

La Boheme, One of Giacomo Puccini’s Most Popular Operas

Immediately after the premiere of Manon Lescaut, I turned my attention to a new project. Over the next two years, I wrote an opera in four acts that became famous and popular into your time in history. La Boheme used a libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa.

I concentrated on showcasing the bohemian lifestyle in France and basing it on the works of Henri Murger. It premiered on February 1, 1896, in Turin, and again to great success. La Boheme quickly became popular, and many companies and theatres staged the opera. It became a significant work of Italy’s musical repertoire.

“These are the laws of the theater: to interest, to surprise, to move. Musical drama must be “seen” in its music as well as art. We must appreciate the outstanding conquests and the courage of foreign composers in the technical field. We must be nourished by them so they can become a part of us, but we must never lose sight of the fundamental characteristics of our art.”

For almost two decades, I spent most of my waking hours working on new operas, releasing them in quick succession. I began to slow down, however, after Tosca and Madame Butterfly.

Image: Poster of La Boheme, a four act opera by Puccini

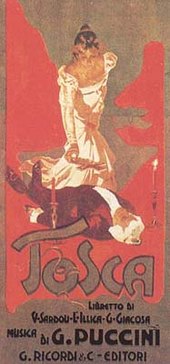

Giacomo Puccini’s Opera,Tosca

In 1889, I had the pleasure of seeing Victorien Sardou’s play La Tosca. Based in Rome during Napoleon’s invasion of Italy, it was a very dark and grim story that inspired me. I wanted to turn it into an opera. “I see in this Tosca the opera I need, with no overblown proportions, no elaborate spectacle, nor will it call for the usual excessive amount of music.”

At first, Ricordi was indecisive. Without the rights to adapt it, I faced legal risk if I moved forward with the project. But once the opportunity to buy the rights presented itself, I couldn’t say no. It was not the end of the issues I had with Tosca. At one point, I abandoned the project altogether when the author of the one-act play, Victorien Sardou, decided his work was too precious to be handed over to a ‘new’ composer such as myself. At that later time of my successful career as a composer, I took great offense to Sardou’s ill-found opinion.

Finally, in 1895, I began the extensive work of turning the French play into an Italian opera; this alone took four years. It also became a project that elicited complaints from my many librettists. Even its premiere held a note of unrest and unhappiness from the audience, with numerous delays and less favorable notice from music critics.

Yet, it was still a success in its own right. Tosca finally premiered on January 14, 1900, at the Teatro Constantine in Rome. Musicologist Joseph Kerman called it a “shabby little shocker.”

Image: Composer Puccini’s opera poster, La Tosca

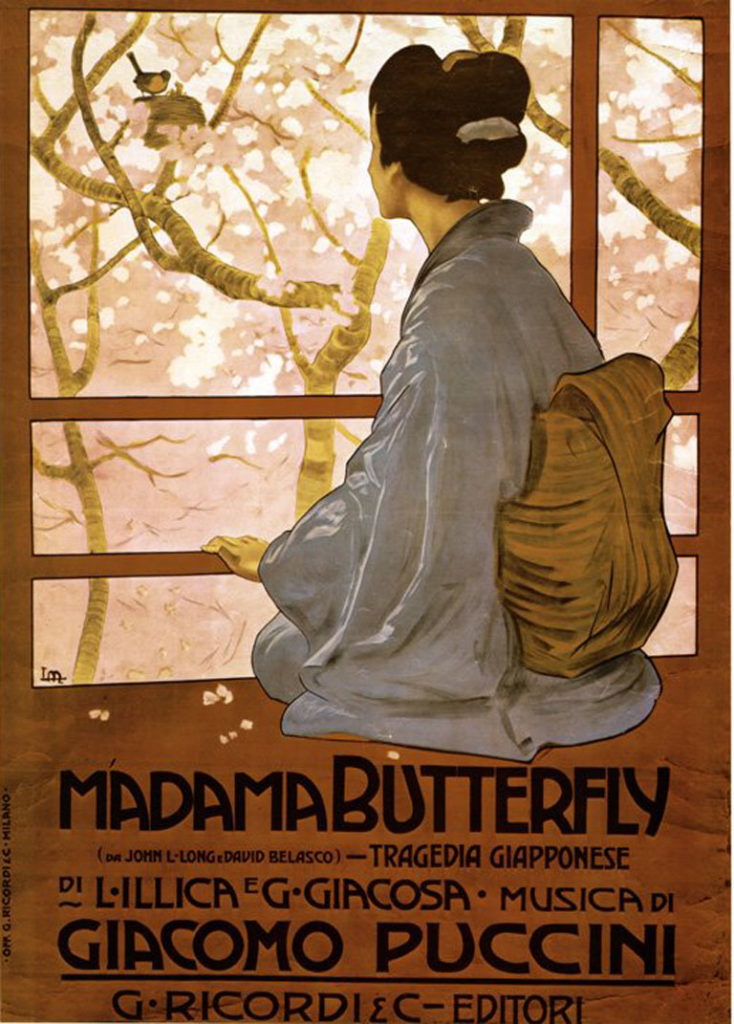

Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, Turandot, & Subsequent Controversy

Concluding the long stint of my many operas composed over a relatively short period was Madama Butterfly. I started working on Madama Butterfly almost immediately after completing Tosca. Based on the short story of the same title by John Luther Long.

The setting for Madame Butterfly was Japan. An Asian account and setting was also the basis of Turnandot. Immediately after their writing – and even more so in your time – cultural misappropriation was levied against me.

Madame Butterfly was and still is a source of controversy. At the time, Western culture viewed Asian countries as ‘other’, and I found myself swept up in the obsession that came with a continent that was described, in part, as erotic. It was deemed racist and also seen as too erotic for the stage.

One critic, Jihei Hashiguchi, stated: “I can say nothing for the music of Madama Butterfly. Western music is too complicated for a Japanese. Even Caruso’s celebrated singing does not appeal very much more than the barking of a dog in faraway woods.” Madame Butterfly became an artwork that suffered from a judgment of unfair and culturally insensitive and misappropriation of Japanese culture and people in the West.

Madame Butterfly benefits as a tear-jerker in terms of story, but the work leans too heavily on buying a fifteen-year-old Japanese Geisha by an American naval officer named B. F. Pinkerton. He marries her, impregnates her, only to return to Japan a few years later with his American wife, and the two of them take Cio-Cio San’s child. It ends in tragedy.

Madame Butterfly has been the subject of debate for many years, with some calling for its removal from the repertoire, while others claim it should remain due to its significance as a historical piece.

Image: Poster for Madame Butterfly, an opera piece composed by Giacomo Puccini

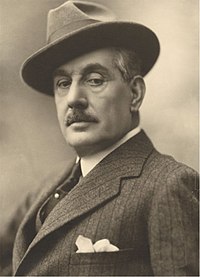

Puccini Suffers A Near-Fatal Accident

I had always been a fanatic of cars and motorbikes, especially when taking long road trips or hunting. By 1900, I was reasonably wealthy, owning property in Torre del Lago, and living what some might consider a very upper-class life.

After commissioning the construction of a particular car that could withstand rugged hunting terrains, I was on my way to a medical exam on February 25, 1903, when I lost control of my custom vehicle. It flipped, and although Elvira and our son, Antonio, escaped with minor injuries, I, unfortunately, suffered a terrible fracture on my leg after being pinned under the car.

A doctor living nearby saved us, but there was not much else I could do except work on Madame Butterfly during the many months after the accident. It seemed like fate that it premiered almost exactly a year after my accident, on February 17, 1904.

Image: Photograph of composer Puccini

In 1910 Giacomo Pucinni Premiers The Girl of the West at the Met of NYC

“When fever updates, it ends by disappearing, and without fever there is no creation. Emotional art is a kind of malady, an exceptional state of mind, over-exciting of every fiber and every atom of one’s being, and so on, ad aeternam. For me, the libretto is nothing to trifle with… It is a question of giving life that will endure, to anything which must be alive before it can be born, and so on until we make a masterpiece.”

After Madame Butterfly’s premiere, I took a break, slowing down on my composition and releasing nothing new until 1910, with The Girl of the West. Based on the play by David Belasco, it was different from my other works. The Girl of the West gained its popularity thanks to the musical score. It premiered on December 10, 1910, at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

Image: A full house at the Metropolitan Opera in NYC

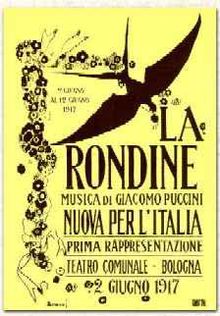

Giacomo Puccini’s Opera, The Swallow

“I have the greatest weakness of being able to write only when my puppet executioners are moving on the scene. If only I could be a purely symphonic writer! I could then at least cheat time. . . and my public. But that was not for me. I was born so many years ago – oh, so many, too many, almost a century… and Almighty God touched me with His little finger and said: “Write for the theater – mind, only for the theater.” And I have obeyed the supreme command.”

My opera, The Swallow, took me three years to write. A Viennese theatre commissioned it in 1913, and I completed it amid the First World War. Due to the politics of the time, including Italy joining the alliance against Austria, Vienna could no longer premiere the piece. I had kept my work separate from politics for most of my life, but the war affected the contract with the Viennese theatre; this theatre ultimately canceled my contract.

Image: Poster for the opera, The Swallow a piece by Puccini

Puccini’s Life & Music Entangled in Political Controversy

Politics became inextricably entwined with my music. After The Swallow, Italian Nationalists commissioned me to compose an ode celebrating Italy’s WWI war victories. My song became a well-known rallying work that was sung and played during Fascist parades and meetings. A year before my death, I was also made an honorary member of the Fascist Party by Benito Mussolini himself and also became an honorary senator of Italy.

Pucinni’s Thoughts, Illness & Death

“That which I have dreamed is always very far from that which I am able to hold fast and write down on paper. An artist seems to me to be a man who looks at me through a pair of glasses which, as he breathes, becomes clouded over and the veils the beauty he sees. He takes out his handkerchief. He cleans his classes. He sees clearly again. But at the first breath the absolute disappears. It is only the veil, the approximation, that we can perceive.”

A year later, in 1924, a chronic sore throat worsened. Because I had been an avid smoker of cigars and cigarettes, I could not escape a throat cancer diagnosis and began radiation therapy to combat growing cancer. But complications from the radiation treatment contributed to a heart attack that struck me down. My relatives buried me in Milan, and then in 1926, my son Antonio arranged for the transfer of my body to our family’s private chapel at Torre del Lago.

“Inspiration is an awakening, a quickening of all man’s faculties, and it is manifested in all high artistic achievements.”

Image: Photograph of composer, Giacomo Puccini

Please find compelling quotes of Giacomo Puccini here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- Giacomo Puccini: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giacomo_Puccini

- Giacomo Puccini: Timeline: https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/giacomo-puccini-486.php

- Puccini and His Cars: https://www.artaxmusic.com/puccini-cars/

- Giacomo Puccini and his World: http://www.pennilesspress.co.uk/NRB/giacomo_puccini_and_his_world.htm

- The Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers: Puccini by Peter Southwell-Sander

- The Lives of the Great Composers by Harold C. Schoenberg

- Return of the Native: Japan in Madama Butterfly by Arthur Gross: https://www.jstor.org/stable/823590?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A0eea75b57d40373cab8b97b302d511d4&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents

- The Madame Butterfly Controversy: Cio-Cio San’s Gender, Racial And Cultural Construction In Orientalist Metaphysics by Hannah Kim: https://yonseijournal.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/butterfly.pdf