Gabriel Fauré’s Early Years In Music

I was born May 2nd, 1845, in Pamiers, Ariège, France. As the youngest son in a family of six boys and one girl, “I grew up a rather quiet, well-behaved child, in an area of great beauty.” None of my brothers displayed any interest or talent in music. Indeed, four of my brothers pursued careers in journalism, politics, and the army. My sister married and became a public servant.

I stayed with a foster parent for my first four years. My biological family finally brought me home only after my father became the director of École Normale d’Instituteurs at Montgauzy, a college for teachers, in 1849.

There was a chapel attached to my school in the town I lived in with my family, and it was there that I showed a great interest in music from a very young age “… but the only thing I remember clearly is the harmonium in that little chapel. Every time I could get away, I ran there. I played atrociously. But I do remember that I was happy, and if that is what it means to have a vocation, then it is a very pleasant thing.”

It wasn’t until an older woman who had heard me play told my father about my musical abilities. That was how my father found out about my musical gift.

In 1853, when I was eight years old, Simon-Lucien Dufaur de Saubiac of the National Assembly heard me play. Monsieur Dufaur told my father, Toussaint-Honoré, that I should attend the School of Classical and Religious Music, where my talents could flourish under proper guidance.

Image: A photo of a young Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Fauré’s Musical Education & Friendship with Camille Saint-Saëns

At age nine, my father sent me to École Niedermeyer music college in Paris. My talents impressed Niedermeyer himself, a Swiss composer employed by the college who accepted me as a pupil right away. I began training as an organist and choirmaster.

Niedermeyer took over the École Choron and renamed it after himself, and he turned it into a school to study church music. I stayed at the school on a scholarship for eleven years. Niedermeyer’s goal was to train the best organists and choir directors.

The classwork itself was something I did not enjoy, and I merely passed. It was with music that I diligently studied and excelled. Besides my classwork, historians have stated that I proved to be a pupil of exceptional talent.

Under the tutelage of Wackenthaler and Niedermeyer himself, I “won the first prize in 1860, followed by another first prize the next year and a by a prize with distinction in 1862” as cataloged by Nectoux’s book Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life.

Camille Saint-Saëns took charge of my piano lessons in 1861 after Niedermeyer retired. I was sixteen at this time. Saint-Saëns broadened the limits of my studies by introducing contemporary music, such as the works of Wagner and Liszt. Thanks to his keen interest in my talent, I became a competent composer.

“After allowing the lessons to run over, he would go to the piano and reveal to us those works of the masters from which the rigorous classical nature of our program of study kept us at a distance and who, moreover, in those far-off years, were scarcely known. …At the time, I was 15 or 16, and from this time dates the almost filial attachment… the immense admiration, the unceasing gratitude I have had for him, throughout my life.”

Camille Saint-Saëns took a keen interest in my musical talent, and he quickly took me under his wing. Although he was only ten years older than me at that time, our professional relationship grew into a strong friendship, and we exchanged an abundance of correspondence over our 60-years of association.

We fell out over opinions on composers numerous times, but we always reconciled, and he remained a steadfast, admired friend. It was difficult to disagree with someone I considered my friend, as well as my mentor, but Saint-Saëns’ stubbornness meant arguments were often unavoidable.

Image: Photo of composers Gabriel Fauré and Camille Saint-Saëns

Gabriel Fauré’s Early Published Compositions

I published my first composition, Trois romances sans parole, in 1863 at 18 while still a student at École Niedermeyer. The Encyclopedia Britannica describes it as “…simple, fraught with persuasive charm and recognizably Fauréenne felicities.”

Trois romances sans parole is indeed a very fluid composition, and a gentle nod to Mendelssohn’s Lieder Ohne Worte. I did delight in infusing traditional forms of music with a “mélange of harmonic daring and a freshness of invention,” as stated by music historians.

At age 20, I graduated as a Laureate in organ, piano, and composition from École Niedermeyer alongside a Maître de Chapelle diploma. My talent opened a variety of doors for me right away after leaving school.

Image: Album cover of Fauré‘s composition, Trois romances sans parole

Gabriel Fauré’s 1st Jobs as a Church Organist

My first appointment was at the Church of Saint-Sauveur at Rennes in Brittany as their chief organist, and I served there for four years. I had a fraught relationship with the parish priest, who questioned my religious dedication.

He was right, too. The priest occasionally noticed me sneaking out for a cigarette. I turned up at Mass one Sunday still in the clothes from the night before, as I had spent the entire night at a ball. I was not there for my religious dedication but only for the opportunity to earn my money as a musician. Following that incident, The priest forced me to resign.

Saint-Saëns helped me gain my second job as an organist by using his influence to secure the Church of Notre-Dame de Clignancourt’s position as an assistant organist.

Image: Composer Gabriel Fauré playing the organ

Gabriel Fauré’s Service During the Franco-Prussion War

The Franco-Prussian war meant I only served at the Church of Notre-Dame de Clignancourt for a few months before France called me to join and serve in the French army for the rest of the year. I took part in the Siege of Paris and saw action at Champigny and several other cities and rural battlefronts. After the war ended, the army awarded me the Croix de Guerre.

Gabriel Fauré’s Teaching Career & Lifelong Friendships

Unfortunately, my return to Paris did not mean the end of the conflict. I managed to escape a brief but bloody battle during the commune, and I traveled to Switzerland, where I secured a position at the same school that had given me my great start in music: École Niedermeyer.

I took on students, some of which became lifelong friends and occasional collaborators, and carved myself a new path in my musical career.

I returned to Paris in October 1871, when I was around 26 years old, and I began to serve as a choirmaster at the Elise Saint-Sulpice under Charles-Marie Widor, who in your time is best known as the composer of the famous Toccata for Organ. He served the dual roles of composer and organist for the church.

Image: Composer Gabriel Fauré at the school École Niedermeyer

Gabriel Fauré Co Founded the Société Nationale Du Musique

Despite my extensive travels, my friendship with Camille Saint-Saëns continued. Together, we visited many salons, including those given by Pauline Garcia-Viardot, with whom Saint-Saëns had introduced me. At those salons, I met famous personalities such as the writer Ivan Turgenev and other composers such as Hector Berlioz (over whom Saint-Saëns and I butted heads once or twice).

Thanks to those meetings, I became a co-founder of the Société Nationale Musique, which helped promote French music. I became its secretary in 1874.

A top violinist performed my violin Sonata at one of the concerts sponsored by the Société Nationale with resounding success. My composition career took a significant leap forward afterward.

Gabriel Fauré’ Failed Engagement to Marianne Viardot

I became engaged to Marianne Viardot when I was 32. I was deeply in love with her, but she called our engagement off for reasons I will not go into, and our crumbling relationship gave me the push I needed to move away from Paris after much cajoling from Saint-Saëns. I began anew in Weimar, where I met Franz Liszt.

Image: Photo of Marianne Viardot

Gabriel Fauré Leaves Paris & Travels Extensively

This move was significant for it gave me a liking to foreign travel, and I indulged in it for the rest of my life. André Messager and I spent a few trips abroad seeing Wagner operas such as Das Rheingold and Die Walküre at the Cologne Opera and Die Meistersinger in Munich and Bayreuth, where we also saw Parsifal.

While traveling, we also performed our joint composition, an upbeat piano party piece based upon Wagner’s Ring operas themes. I admired Wagner, and it was disappointing that I never came under his influence.

Gabriel Fauré’s Marriage, Family & Romantic Affairs

I did finally married in the year 1883. My new wife was Marie Fremiet, the daughter of Emmanuel Fermiet, a sculptor. I was in my late thirties and still a bachelor, and a good friend of mine who fancied herself a match-maker put three names in a hat, and I drew one out. I was not happy with the idea of wooing someone else after everything that had happened with Marianne.

Thankfully, there was no romance in the process. Marie’s mother took charge of all the arrangements. We married on March 27th, 1883.

We had two sons Emmanuel and Philippe. Emmanuel became a world-renowned biologist, and Philippe became a writer. He wrote biographies about his grandfather and me.

In my eyes, our marriage was splendid, but Marie did not enjoy how absent I was to our relationship — and did not accept my numerous love affairs. Marie felt that her domestic life smothered her creativity. While I composed, worked, and traveled, she remained home to mother our children. She earned some income from painting fans.

Our relationship worked best at a distance, and I carried on my affairs with discretion even though it pained my wife. Although our marriage and the stability of having a family worked wonders for my creativity, I missed my freedom. My affairs gave me a well-needed escape and inspired me.

Image: Photo of composer Gabriel Fauré and his wife, Marie Fremiet

Gabriel Fauré’s Financial Struggles

During my 30’s years, I struggled financially to provide enough money to support my family. I played the organ for church services most days at Elise de La Madeleine. I also had a private studio teaching music harmony and the piano, carving out whatever time I could to compose my own music. I managed to sell the few I completed to a publisher, who paid a mere 50 francs, on average, per piece without paying me ongoing royalties.

Gabriel Fauré Struggles with Bouts of Depression

It was in my thirties that I began to suffer bouts of depression. Perhaps my broken engagement to write a new opera that included a lucrative commission contributed to my mental health difficulties.

I had no choice but to abort writing the opera because the librettist, Paul Verlaine, could not deliver a libretto due to his excessive drinking. That is when I sunk into a much lower state of functioning.

My friends and family were worried. A change of location seemed like an exciting remedy to the people close to me and me. I accepted an invitation to stay in Venice at the home of my friend and arts patron, Winnaretta Singer-Polignac – who was heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune. She sponsored music salons and commissioned works from many composers of the time. She put me up in her large house, where I had time to recover.

Once in Venice, Venice, I was inspired to compose again, composing the first five Mélodies de Venise to the words of Paul Verlaine. To my chagrin, I continued to admire the man’s poetry even after the opera debacle.

Gabriel Fauré’s Love Affair with Emma Bardac, the Future Wife of Claude Debbusy

I began an affair with Emma Bardac while in my late forties. It was a fulfilling relationship lasting over four years. My love for her – a singer who was intellectual and alluring – inspired me to write the song cycle La Bonne Chanson. Emma was an incredible vocalist, and I dedicated the piece to her.

I also wrote the Dolly Suite for Piano Duet and dedicated it to Emma’s daughter, Hélène, or ‘Dolly,’ as she was better known. There was some speculation that Dolly was my biological daughter, but history has shown that was not the case. But for me, she was like a daughter.

Despite my love for Emma, our romance did not last. She may have grown impatient with mistress status, as I was unwilling to leave my wife, Maria. Another factor perhaps was our age difference. I was 17 years her senior. After our affair ended, she and Claude Debbusy had an affair that eventually resulted in the birth of their daughter, Claud-Emma, and their marriage.

Image: Photo of Emma Bardac

Gabriel Fauré’s Employment at the Paris Conservatory

My fortunes improved in the 1890’s when I was in my mid-40’s. I became a professor of composition at the Paris Conservatory in 1892. Saint-Saëns encouraged me to apply after the death of Ernest Guiraud, the Conservatory’s professor of music composition.

The Paris Conservatory was a politically charged institution. The current director did not want me to teach music composition, as my compositional style was considered too radical at that time.

Instead of teaching music composition, The Conservatory initially assigned me the role of inspector of the music conservatories in the provinces. Although business traveling was not enjoyable for me, the inspector position provided a steady income to support my family financially.

Gabriel Fauré Influences Future Generations of Composers

When the famous opera composer Jules Massenet, a music composition teacher at the Conservatory, was passed up to become the new director, he resigned, opening a position for me to teach music composition.

I had a way of teaching composers that was unusual for that time. I made sure that they had a good grounding in music construction, including harmony and knowledge of a broad range of repertoire, but did not prescribe how they should compose. Instead, I sought to help them grow in confidence in their unique way of writing music.

My students included Maurice Ravel, Florent Schmitt, Charles Koechlin, and Nadia Boulanger, who became the famous composition teacher to many 20th century composers, including Aaron Copeland and Quincy Jones.

In 1897, I met Maurice Ravel in music composition class. He became one of my students, and we forged a long-lasting, mutually respectful relationship. He worked hard at his craft, but he had lost many music competitions despite his talent and diligence.

I wanted to help him and did give him some direction. At that time, he was writing his now-famous string quartet. My feedback was helpful to him. Ravel dedicated his String Quartet in F Major to me.

Image: Composer Gabriel Fauré writing compositions

Gabriel Fauré Becomes the Director & Reforms The Paris Conservatory

I taught students as I had once been myself about the art of composition, music, and all of its nuances. In 1905, now sixty years old, I succeeded Théodore Dubois as the Conservatory director after a scandal had forced his hand in bringing his retirement forward.

I succeeded happily, and I changed the administration and curriculum by appointing independent external judges to decide on admissions, examinations, and competitions.

Of course, as change often does, the faculty members were not happy with my decision, and many resigned. I was dubbed “Robespierre” (after Maximilien Robespierre, known well for his role during the Reign of Terror against the political adversaries who opposed the Revolution).

Directing the Paris Conservatory came with its ups and downs. Although the directorship helped me financially, it challenged my creative growth. I struggled to compose and made no more headway with it than at my time of teaching organ and piano so many years previously.It was not until I took time off at the end of each summer to live in a hotel room by a Swiss lake that I began to compose again in earnest. That is when I wrote the opera Pénélope and La chanson d’Ève, a piano piece. My works bridged the end of the Romantic period in music with the beginning of the modern era.

Image: The Paris Conservatory, where Fauré becomes the director

Gabriel Fauré’s Rise in Popularity in the 19th Century

By the Nineteenth Century, my popularity gained momentum in Britain, but not in countries like Germany and Russia, where my music’s acceptance lagged. My trips to England gave me ample opportunity to perform my pieces, and I performed at Buckingham Palace in 1908 at age 63. I “excelled not only as a songwriter of great refinement and sensitivity but also as a composer in every branch of chamber music.”

In 1909, when I was 64, I was elected to the Institut de France after much persuasion from my influential father-in-law and Saint-Saëns. I won the ballot by a small margin. It was in that year that I also became president of the Société Musicale Indépendante after the Société Nationale de Musique disbanded.

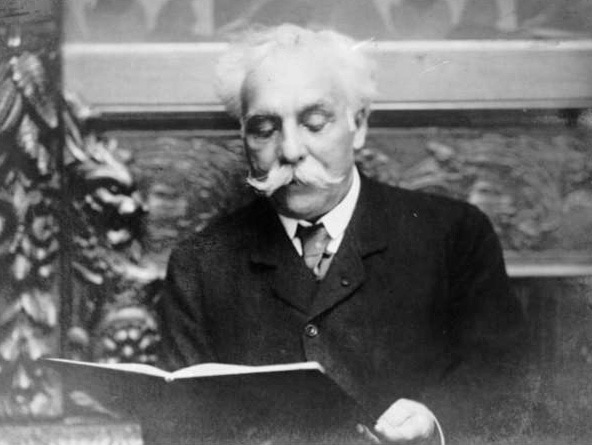

Gabriel Fauré Loses His Hearing, but Still Composes

Unfortunately, in these last two decades of my life, I began to suffer from increasing deafness that caused my compositions to change, according to reviews, in sound.

My ability to hear pitch accurately became impaired with both the high and low register sounding out of tune. Because of this, critics described my music as “elusive and withdrawn in character, and at other times turbulent and impassioned.”

I composed over one hundred songs during my musical career, including Après un rêve in 1865, Les Roses d’Ispahan in 1884. I “enriched the literature of piano with a number of highly original and exquisitely wrought works.”However, my most famous works were my Ballade for Piano and Orchestra in 1881, two sonatas for violin and piano, and Berceuse for Violin and Piano in 1880. Elégie for Cello and Piano (1880) and two sonatas for cello and piano frequently performed and recorded up to this current age.

Image: Album cover to Après un rêve, composed by Fauré, Debussy, and Ravel

Gabriel Fauré’s Incidental Opera Music

I also composed some incidental music for plays such as Pelléas et Mélisande when I was 53 (1898) and two lyric dramas: Prométhée and Pénélope. Prométhée was a lyrical tragedy designed to be performed outside in the Amphitheater at Béziers. It took a lot of vocal force! It premiered in August of 1900 and was a huge success.

Between 1903 through around 1921, I had an income stream through writing criticism for the publication Le Figaro. It was not a role I enjoyed, nor was appreciated for, as it was hard for me to write biting criticism of my fellow composers and performing musicians. Additionally, I was more broadminded and accepting of new musical thought, highlighting the positives of a musical piece rather than the negatives.

Image: Painting of the Pelléas et Mélisande, composed by Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Fauré Refuses to Boycott & Criticise German Music

When the First World War commenced, I was almost stranded in Germany. I stealthily made my way to Switzerland. Once there, I managed to return to France.

Due to the hate felt in Europe against Germany, Saint-Saëns declared that he was organizing a boycott of German music. I disagreed with this, and therefore disassociated myself from the movement, along with the composer, Messager.

Fortunately, parting ways with Saint-Saëns on this issue did not adversely affect our friendship.

I saw in my art “a language belonging to a country so far above all others that it is dragged down when it has to express feelings or individual traits that belong to any particular nation.”

In January 1905, when I was sixty years old, I wrote about the criticisms of my music in Germany:

“The criticisms of my music have been that it’s a bit cold and too well brought up! There’s no question about it; French and Germany are two different things.”

Gabriel Fauré’s Death & Legacy

Unfortunately, I passed away at age 79 on November 4th, 1924, after a battle with pneumonia. I was given a state funeral at Elise de la Madeleine and cremated at the Cemetiere de Passy in Paris.

After my passing, the Paris Conservatory returned to its old ways. They abandoned my changes and became resistant to new trends in music. My harmonic practice became the limit to which students should not cross and my successor, Henri Rabaud, declared that “modernism is the enemy.”

In a tribute in 1945, Leslie Orrey stated, “More profound than Saint-Saëns, more varied than Lalo, more spontaneous than d’Indy, more classic than Debussy, Gabriel Fauré is the master par excellence of French music, the perfect mirror of our musical genius.” That is a legacy well worth leaving behind.

Image: Painting of Gabriel Fauré

Please find compelling quotes of Gabriel Fauré here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

• Encyclopedia Britannica: britannica.com/biography/gabriel-faure

• BBC Music: bbc.co.uk/music/artists/fa19a8b6-e7f4-40d4-af15-7a7c41ac7d8f

• The Famous People: thefamouspeople.com/profiles/gabriel-fauer-6874.php

• Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life by Jean-Michel Nectoux

• The Independent: independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/classical/features/the-complex-harmonies-of-a-classical-triad-2131561.html

• Music Web: musicweb-international.com/classrev/2006/Mar06/Saint-saens_faure_book.htm

• Wikipedia: wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriel_Faur%C3%A9

• Gabriel Fauré: The Songs and their Poets by Graham Johnson

• Naxos: https://www.naxos.com/mainsite/blurbs_reviews.asp?item_code=8.554722&catNum=554722&filetype=About%20this%20Recording&language=English#:~:text=’%20In%201897%2C%20he%20went%20to,failing%20the%20various%20Conservatoire%20examinations.