Claude Debussy, Composer

Claude Debussy is perhaps the most influential French composer in western music. His influence was prominently felt for composers who were contemporaries and in the decades to follow. Debussy’s music continues to be influential in our time for 21st century composers. Musicians and audiences alike are swept away by the beauty, color and brilliance of his music. As if he could speak from the afterlife, Debussy tells his life story (based on scholarly sources). Quotation marks indicate Debussy’s exact words.

Early Life of Claude Debussy

Unlike other composers, I was born into a family that lacked artistic finesse on August 22, 1862. My parents had a china shop that failed, and we moved to Paris in search of better fortune. At the time of the move, the Siege of Paris was taking place, so my mother took me and my sister to my aunt’s home in Cannes.

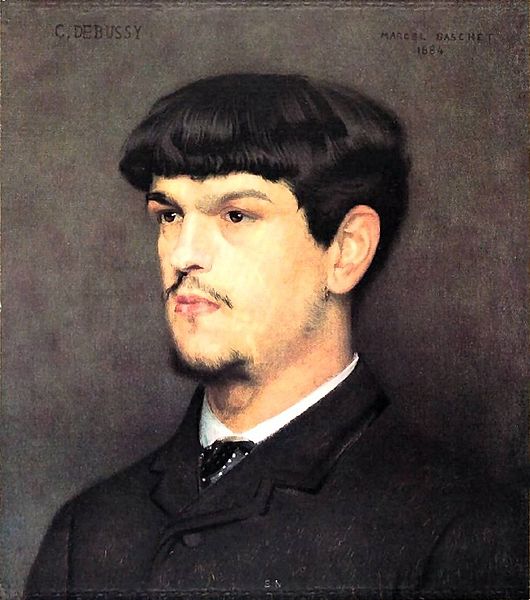

Image: A portrait painting of a young Claude Debussy.

My aunt was taken with me, and she believed I had a hidden talent. She hired an old Italian professor, Jean Cerutti, to teach me how to play the piano, while she taught me how to read and write. Although I learned and picked up on the lessons quite quickly, there was no hidden, secret talent, unfortunately. Once we left my aunt’s house after the Paris Commune, my music lessons were quickly forgotten.

In fact, it wasn’t until my father introduced me to Charles de Sivry (also known as the “Prince of Poets”) whom he’d met in prison that I began learning again. De Sivry took me to his mother, who had been a student of Chopin, and after some to and fro she agreed to take me on as a pupil. Apparently, she once said, “That boy must be a musician.” And that was her seal of approval — one that would later be the reason for my entrance into the Conservatory.

Claude Debussy’s Time at The Paris Conservatory

Thanks to her teachings, I joined the Paris Conservatory at only ten years old, in 1873. I first studied under Antoine François Marmontel, and won awards between 1874 and 1876 in different classes. Although I had no hidden talent, I found myself working hard to impress. Marmontel believed in me and believed in what I could do, and so I applied myself even more under his tutelage.

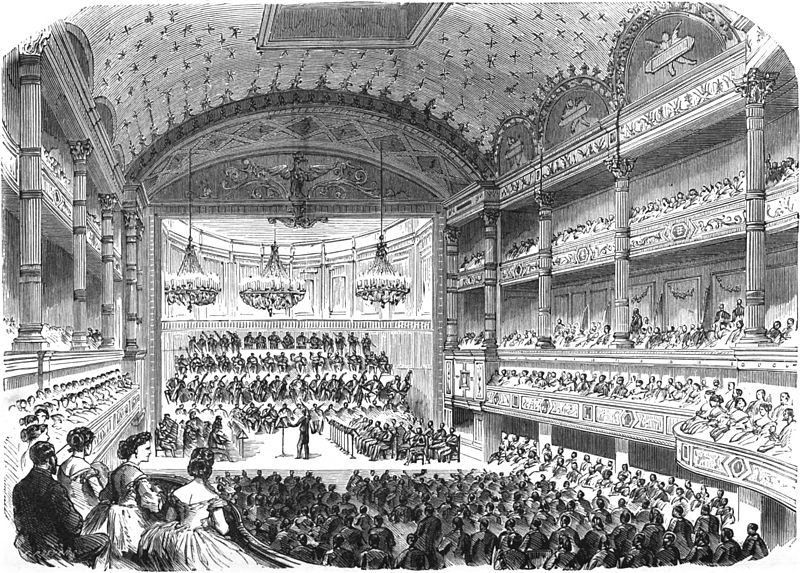

Image: A drawing of a performance in the concert hall of the Paris Conservatory of Music

It was the second prize in 1877, when I was fifteen, where I played Schumann’s G Minor Sonata, that I realized I wanted to compete for the Prix de Rome. By then, I had become more interested in composition. While Marmontel had nothing but good things to say about myself, my harmony teacher thought differently. “Debussy would be an excellent pupil if he were less sketchy and less cavalier.” He did not enjoy the bending of the rules to suit my style of music. I remember he listened to me practice one day and was not impressed with what he heard. He’d said, “Don’t you understand the principles of harmony?” I’d said not his idea of harmony, no, but that I understood my style, my music. My time at the Conservatory can be described as bittersweet because of how torn my teachers were: they either loved me or hated me.

In 1874, I won an award for my performance of Chopin’s Second Piano Concerto, and was awarded the deuxieme accessit. I later received a premier accessit in 1875, and yet another second prize in 1877. However, my failures in 1878 and 1879 meant I could not continue piano classes at the Conservatory.

New Opportunities for Claude Debussy

In 1879, at seventeen, I picked up a summer job as a resident pianist at the Château de Chenonceau. It was during this time that I composed my Ballad à la Lune. A year later, I took on another job for Nadezhda von Meck. While working as a pianist in her household, I was able to travel and also create compositions for Tchaikovsky himself, such as piano duets for Swan Lake.

Image: A photograph of Claude Debussy playing piano while others watch on.

Claude Debussy’s First Love

It was while working for von Meck that I met Marie Vasnier in 1880. She was a great inspiration to me, and I composed around twenty-seven songs for her. Although she was married at the time, Marie and I became involved in a love affair. Her husband might not have minded, for we remained on good terms, and nothing much was said about it.

Claude Debussy and The Prix de Rome

In the meantime, I was stirring controversy at the Conservatory. Despite disapproval from the faculty at my flaunting of composition rules, I won the Prix de Rome in 1884 with my cantata L’Enfant prodigue. It received twenty-two out of twenty-eight votes and with it the prize. I was sent to live at the Villa Medici in Rome, leaving Italy only to visit Marie Vasnier on occasion.

Image: Painting portrait of Marie Vasnier.

My time at the Villa is not one I remember fondly. I battled with depression so deep that I could not compose, and only felt myself when I visited Marie. I wrote to a friend once, saying, “I cannot bear to be separated from Mrs. Vasnier. I told you that I have become too used to wanting and conceiving only by her…” The accommodation, music and food were not to my taste, either, and staying in Rome felt more like torture than an enjoyable, memorable experience.

It wasn’t until 1885, at twenty-three, when I decided to go my own way that things began getting better. “I am sure the Institute would not approve, for, naturally it regards the path which it ordains as the only right one. But there is no help for it! I am too enamored of my freedom, too fond of my own ideas!”

The Influence of Gamelan Music on Claude Debussy

In 1889, at twenty-seven, I attended a performance by an Indonesian gamelan group. Gamelan music was a series of percussion instruments, and was often an orchestra. It was so different to anything I had ever heard, and so curious was I by how the instruments worked, that I found myself deeply inspired by this music. I composed a piano piece named Pagodes due to the inspiration of gamelan music.

Claude Debussy’s Stirring Controversy

Finally, I managed to compose two pieces for the Academy: Zuleima and La Damoiselle élue. With La Damoiselle élue, I had wanted to create “a little oratorio in a little pagan mystical note.” However, my musical style was not to everyone’s taste. The Academy said my music was “bizarre, incomprehensible, and unperformable.” Needless to say, they were not impressed with my work. The only other piece I managed to mostly complete while in Rome was my Ariettes oubliées, which were inspired by poems written by Paul Verlaine, and I dedicated them to Mary Garden, whom would go on to sing the role of Mélisande.

Image: Painting of Melisande Opera

Inspiration came to me in many forms. Usually, I was influenced by turmoils in my life. However, upon my return to Paris in 1887, I discovered Wagner’s music. As a fan of Bach, I found myself conflicted about Wagner. I loved Tristan and Isolde, and went to Bayreuth to watch Parsifal and die Meistersinger, and although Wagner had some influence to my work, I didn’t find myself completely swept up by his talent like other composers.

When I was twenty-eight, in 1890, my coveted affair with Marie Vasnier ended. We remained on good terms and I composed and dedicated Mandolin to her. That same year, I met Erik Satie. We became good friends immediately: I found myself drawn to his lifestyle, so similar to mine, and we seemed to enjoy many of the same things.

Debussy’s New Romance and the Societe Nationale de Musique

That year, I also met Gabrielle Dupont, or ‘Gaby.’ I was incredibly taken with her, “…the most remarkable thing about the appearance of this pretty blonde was the strikingly green color of her eyes. She was certainly the least frivolous blonde I ever came across. Her chin was forceful, she was strongly built and looked at you as resolutely as a cat.” Gaby was my support pillar for a long time. While I created music and tried to make a name for myself, Gaby earned the money that helped us survive during some of the worst financial times of my life. We were also receiving financial aid from friends, which would later come back to bite me.

Image: Portrait painting of “Gaby” Gabrielle Josephine du Pont.

In 1893, at thirty-one, I was elected to the committee of the Société Nationale de Musique, where my String Quartet was premiered by Ysaye later that year.

Claude Debussy and the Pelléas et Mélisande and A Scandalous Affair

In May 1893, I attended the theatre to watch Pelléas et Mélisande. I then traveled to Maurice Maeterlinck’s home to ask consent for an operatic adaptation, so taken was I with his play. Maeterlinck readily agreed to the adaptation, and I began working on it right away.

After completing Act I of Pelléas et Mélisande, I began an affair with Thérèse Roger while still living with Gaby. It did not go unnoticed.”Gaby with her steely eyes found a letter in my pocket which left no doubt as to the advanced stage of a love affair with all the romantic trappings to move the most hardened heart. Whereupon tears, drama, a real revolver and a report in the Petit Journal. Ah, my dear fellow, why weren’t you here to help me out of this nasty mess? It was all barbarous, useless and will change absolutely nothing. A moth’s kisses or a body’s caresses can’t be effaced with an India-rubber. Mind you, they might perhaps think of something like this and call it the Adulterer’s India Rubber. On top of it all, poor little Gaby lost her father – an occurrence which for the time being has straightened things out. I was, all the same, very upset … “ The Petit Journal was a French daily newspaper, and anything of any import or gossip was published and circulated quickly. It did not take long for things to go south.

I announced my engagement to Roger in 1894, when I was thirty-two, after telling her that Gaby and I had split. Our good news was met with condemnation so loud that many of my friends distanced themselves, and colleagues disowned me. One of my financial supporters, Eric Chausson was so livid with the announcement that he went to the Petit Journal, too. My mistreatment of women became a very popular subject with anonymous letters circulating, denouncing my relationship with women and financial woes. It was embarrassing.

Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel

Along the same lines of controversy, my relationship with Maurice Ravel was one that caused waves of dissent among our fans. One could say we influenced each other, but I believed strongly that Ravel took liberties with music that strongly resembled my own creations. We were both seen as “impressionists” of our times, which Ravel did not appreciate at all.

Image: Photograph of Maurice Ravel

Our friendship was unlikely at best, and it ended rather quickly once Pierre Lalo, a critic, stated, “Where M. Debussy is all sensitivity, M. Ravel is all insensitivity, borrowing without hesitation not only the technique but the sensitivity of other people.” After his statement, the tide on either side grew, and it became impossible to fight the idea that Ravel was copying me in every way.

It did not help that, later on, he was one of the people who had stuck his nose in my affair and took my wife, Lilly’s side, in something that had nothing to do with him.

Claude Debussy and Marriage

In the end, I returned to Gaby only for her to leave me eventually, and I met her friend Marie-Rosalie Texier, also known as “Lilly.” “She is unbelievably fair and pretty, like some character from an old legend… Her favourite song is a roundelay about a grenadier with a red face who wears a hat on one side like an old campaigner, not very provoking aesthetically…She does not have much up top.”

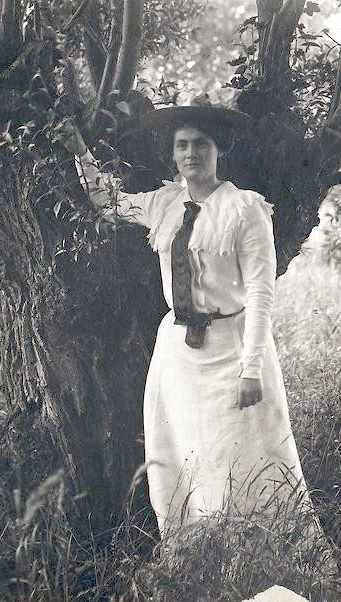

Image: A photograph of “Lily” Marie-Rosalie Texier posed by a tree, Debussy’s first wife.

Frankly, I grew irritated with Lilly’s lack of educational finesse. However, after threatening to kill myself, and against’s Gaby’s protests, Lilly and I got married on October 19, 1989, with Erik Satie as our witness.

I dedicated Sirens from Nocturnes to her, but it was not long before I began to fall out of love with her, and found her voice and shrill laughter grating. Our marriage would last less than five years.

Claude Debussy Finishing Pelleas et Melisande: A Resounding Success

I completed Pélleas in 1894. Unlike other projects I had started, Pelléas et Mélisande was the perfect opportunity to write music I liked. “The drama of Pelléas which, despite its dream-like atmosphere, contains far more humanity than those so-called ‘real-life documents’, seemed to suit my intentions admirably. In it there is an evocative language whose sensitivity could be extended into music and into the orchestral backcloth.”

Image: Photograph of Act 4 of the original 1902 production of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande.

Struggling to find a venue for the opera, I approached André Messager after he became conductor of the Opéra-Comique. He, a fan of my work, then persuaded Albert Carré, the head of the opera house, to listen to my music. In 1901, Carre finally agreed to stage the opera at the Opéra-Comique.

Even then, the staging and rehearsals did not go smoothly. Maeterlinck was adamant he wanted Georgette Leblanc to sing the role of Melisande, but I had become quite taken with a new singer, Mary Garden. “That was the gentle voice that I had heard in my inmost being, with its hesitantly tender and captivating charm, such that I had barely dared to hope for.”

Maeterlinck was livid with my decision, so much so he tried to legally stop me from setting up the performance. Thankfully, the signed documents stating his permission had been freely given proved useful in this context, and one night he even turned up to my house, where Lilly met him at the door and stopped him from giving me a few “whacks” as he’d promised. It wasn’t until he watched the opera in 1920 that Maeterlinck admitted I was right and he was wrong: Mary Garden had been the best choice for the role.

The opera opened on 30 April 1902 to resounding success. The Apaches (a group of artists led primarily by Maurice Ravel where musicians could perform new music and discuss politics in peace), in particular, were very supportive of my work and ended up attending all fourteen performances. I had begun attending their meetings a year previously.

Claude Debussy Writing the La Revue Blanche and a Scandalous Romance

In 1901, I worked as a music critic for La Revue Blanche, under the name Monsieur Croche. My reviews would later be published as a book titled “Monsieur Croche, Antidilettante.” I was also tutoring at the time and in 1903, when I was forty-one, another scandal caused turmoil in my life. I had just been appointed a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur. At the time I had begun a teaching position, and one of my students was Raoul Bardac. Raoul introduced me to his mother, Emma, and we both grew very attracted to each other quite quickly.

Image: Photograph of Claude Debussy and his wife second wife, Emma Bardac.

The affair continued in secret for a year, and on July 15 1904, I sent Lilly away and took Emma to Jersey, then Normandy, on holiday. By August 11, I knew I could not continue my marriage to my wife, and wrote her a letter ending things.

On October 14, Lilly attempted suicide by shooting herself in the chest. It did not kill her but paralyzed her instead. The scandal caused Emma’s family to disown her, and me to lose many more friends, supporters, and colleagues, one of them being Messager of the Opéra-Comique. Paris became intolerable. I could not work, or enjoy myself, and had very few people I could count on. “You should know how many people have deserted me. It is enough to make one sick of everyone called man… Morally, I have suffered terribly… I don’t know, but I’ve often had to smile so that no one should see that I was going to cry.”

When a group of old friends of mine banded together to support Lilly financially, I decided to take Emma to England. She was pregnant. Mary Garden once said, “I honestly don’t know if Debussy ever loved anybody really. He loved his music — and perhaps himself. I think he was wrapped up in his genius.” However, I was completely besotted with my daughter, Claude-Emma, also known as Chouchou. She was born 30 October, 1905. Unfortunately, married life with Emma was not what I was hoping for, and our relationship deteriorated although we never separated nor divorced.

Claude Debussy and Igor Stravinsky, Claude De The Rite of Spring

My friendship with Stravinsky was borne of admiration. I had heard of him, at first, in 1910, when Stravinsky presented The Firebird and I had been sat in the audience. I had found it imperfect, but “very fine” and it launched Stravinsky’s career.

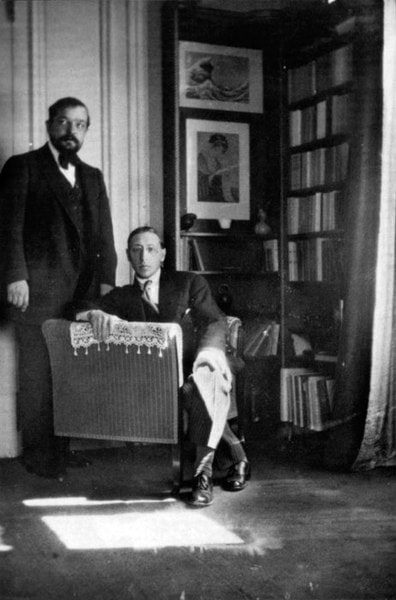

Image: A photograph of Claude Debussy standing next to Igor Stravinsky sitting in a chair.

In the same vein, Stravinsky admired me, my work and my talent as a pianist and as a composer. It was not long before we became friends, especially after I attended the performance of Petrushka. I had written to him shortly after, saying, “Thanks to you, I have passed an enjoyable Easter vacation in company of Petrushka, the terrible Moor and the delicious Ballerina. I can imagine that you spent incomparable moments with the three puppets… I don’t know many things of greater worth than the section you call ‘Tour de passé-passé.’ There is in it a kind of sonorous magic, a mysterious transformation of mechanical souls which become human by a spell of which, until now, you seem to be the unique inventor. Finally, there is an orchestral infallibility that I have found only in Parsifal. You will understand what I mean, of course. You will go much further than Petrushka, it is certain, but you can be proud already for the achievement of this work.”

I influenced Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring after playing a piece that was too “primitive” for my works. It inspired him to use that small piece and create a masterpiece that later revolutionized music. In fact, its premier was so successful it caused a riot. People loved it and hated it, and it overshadowed any other musical premier including my own of Jeux. I also helped my friend Igor Stravinsky by playing one of the parts for his 4-hands piano arrangement of Le Sacre du Printemps. He made this arrangement, and we played through it, so he could test out the piece prior to orchestrating it.

Claude Debussy and The Opera, La mer

In October 1905, when I was forty-three, La mer premiered to a very mixed reception. La mer was composed over two years, and was not as well received as I had hoped when it premiered. Once critic said, “The audience seemed rather disappointed: they expected the ocean, something big, something colossal, but they were served instead with some agitated water in a saucer.” I believe the reason for La mer’s flop was because of the reputation I had created for myself. People still disapproved of my romanticisms and did not accept me as a person.

I conducted Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune and Nocturnes at Queen’s Hall in London in 1909, and in May Pelleas et Melisande’s first production at Convent Garden premiered.

Claude Debussy’s Ill-Health and Death

That same year, I was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. I would receive surgery in 1915 to alleviate some of the pain, but it didn’t work to the extent we were hoping for. “There are some mornings when the effort of dressing seems like one of the twelve labors of Hercules.”

Sergei Diaghilev would end up commissioning one of my last works in 1912. It was titled Jeux. Its premier was lukewarm at best, but I blame the fact that Stravinsky’s The Rites of Spring overshadowed Jeux.

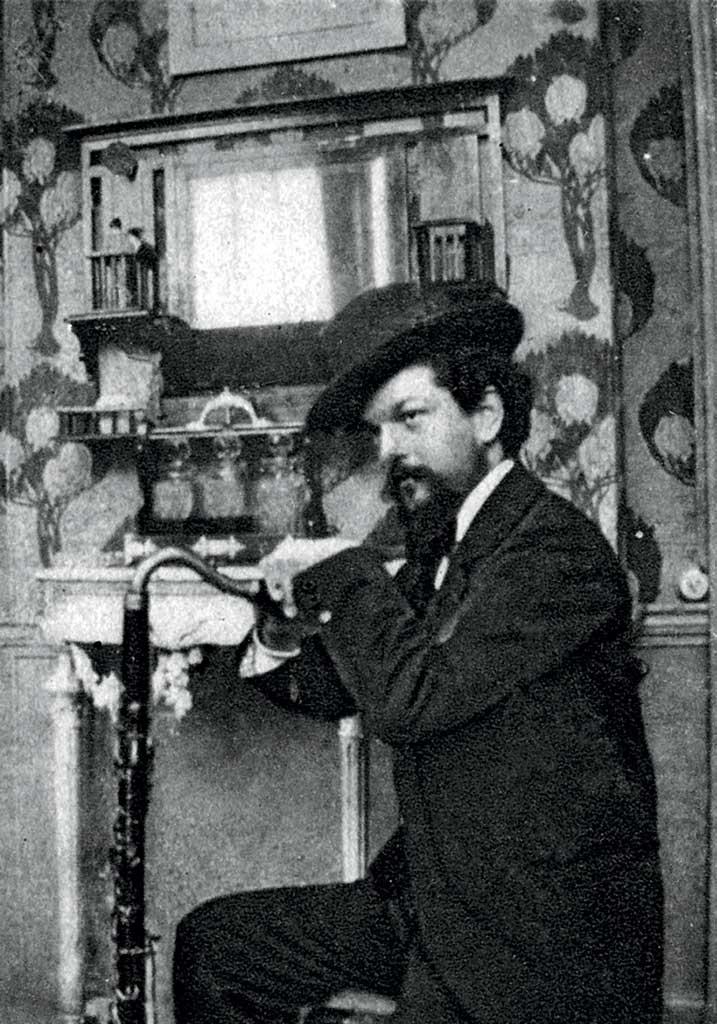

Image: Photograph of Claude Debussy posed with a bassoon.

My last concert was the premiere of my Violin Sonata on September 14, 1917. My health declined considerably after, and I became bedridden in 1918, at the age of fifty-six. Before I died, I made sure to be rid of any work I deemed imperfect. I died in the March of that year, in the middle of the First World War, to the sound of bombs and artillery.

Because of the circumstances, a public funeral was not held for me. Instead, a parade led my coffin to my temporary burial spot at Père Lachaise Cemetery, and I would be reinterred later in Passy Cemetery. I was joined a short while later by my daughter, and then my wife.

Please find compelling quotes of Claude Debussy here on his quotes page.

REFERENCES

- Famous Composers by Nathan Haskell Doyle (George G Harrap & Company)

- Great Composers by Gervase Hughes (Pan Books, 1964)

- Claude Debussy: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Claude-Debussy

- Claude Debussy and the Prix de Rome: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Debussy#Prix_de_Rome

- Paul Verlaine: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Verlaine

- Debussy’s Women: https://mldd.blogspot.com/2012/05/claude-debussy-150-years-4-women.html

- Debussy’s Wives: https://interlude.hk/debussys-wives/

- Debussy: https://www.rodoni.ch/OPERNHAUS/pelleas/Debussy2.pdf

- Pelleas et Mélisande: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pell%C3%A9as_et_M%C3%A9lisande_(opera)

- Igor Stravinsky: http://www.petruschka-klavierfestival.de/index.asp?level1=5&level2=1&page=0&lang=2&pdt=4

- The Gamelan Influence: https://www.wqxr.org/story/gamelan-influence/

- Contrastic Debussy and Ravel: https://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/22155#:~:text=Claude%20Debussy%20and%20Maurice%20Ravel,epoch%20of%20rich%20cultural%20confluence.&text=Each%20composer%20was%20at%20times,or%20borrowing%20from%20the%20other.