Charles Gounod’s Early Years Shaped by the Death of His Father

I was born on June 17th, 1818, in Paris to an artistic family. My father was a painter, my mother a talented pianist who, on occasion, gave lessons to musically inclined students. Francois, my father, was, at one point, the official artist to a member of the royal family, and so for the first early years of my life, we lived at the Palace of Versailles.

When only five years old, I suffered the loss of my father. After his death, my mother resumed teaching lessons to provide a stable income to our household. Unlike some composers, I was lucky to have my inclination towards music and composing supported by my mother. She taught me about music, introducing me to the piano from a young age.

Image: Photo of a young Charles Gounod, composer

A French critic, Martin Cooper, said: “A life with a widowed mother who was also his first guide and the one who formed his earliest musical taste played… a considerable part in determining the complexion of his musical personality. His artistic inclinations never met any opposition at home, were indeed fostered in an atmosphere of emotional intimacy rather too exclusively feminine; so that it was only later, and so to speak as one removed from life as Gounod had come to know it, that he developed the harder, more masculine qualities; and this lack – due partly, no doubt, to temperament, but certainly not corrected by circumstances and early environment – made itself permanently felt.”

Charles Gounod’s Musical Education at the Paris Conservatory

After some years spent at a boarding school, I finished my education at the Lycee Saint-Louis. I was a good student, especially in Latin and Greek, but the music was where my heart lay, and everything else paled in comparison. Mozart’s Don Giovanni was a huge inspiration. After listening, “I felt as if I were in some temple as if a heavenly vision might shortly rise before my sight… Oh, what a night! What a rapture! What Elysium!”

Image: Paris Conservatory in Paris, France

I begged my mother to leave the Lycee. Although she was not against the idea of me focusing on music solely, she did not want me to go into the world just yet. After speaking to the director of the Lycee – and both my mother and the director agreeing I would become a musician – I was admitted to the Conservatoire de Paris in 1836.

At the conservatory, I studied composition under the tutelage of Fromental Halevy, Henri Berton, Jean Lesueur, and Ferdinando Paer. In 1836, my cantata Marie Stuart et Rizzio won the Prix de Rome, with Fernand winning the Grand Prix in 1838.

Charles Gounod’s Scholarship to the French Institute in Rome

My hard work was rewarded. In 1838, at twenty years old, I traveled to the French Institute in Rome. For me, heading to Italy was a dream come true. As religious as my family and I had been, a three-year stay in Rome was wholly inspiring.

While I was in Rome, I read Goethe’s Faust and began toying with the idea (and sketching!) of turning it into an opera. I was pushed and cajoled by newly made friendships to take a step towards opera: Pauline Viardot and Fanny Hensel, whose brother was Felix Mendelssohn, and I later met him in Vienna.

Image: French Institute in Rome, Italy

During my time there, I met a preacher called Henri-Dominique Lacordaire, and he introduced me to the great works of Michelangelo and the music of Palestrina.

Giovanni Pierlugi da Palestrina was an Italian Renaissance composer. I studied his works in depth, cherishing every note, every piece. Palestrina’s inspiration would later prompt me to become a priest. I studied theology for two years, but I could not take the vows when the time came.

“The 1848 Revolution had just broken out when I left my job as a musical director at the Eglise des Missions etrangeres. I had done it for four and a half years, and I had learned a lot from it, but as far as my future career was concerned, it had left me vegetating without any prospects. There’s only one place where a composer can make a name for himself: the theatre.”

In my last year of the scholarship, I left Rome and traveled to Austria. In Vienna, I attended a showing of Mozart’s The Magic Flute, and, surprisingly, my Requiem Mass was programmed and performed on behalf of the leading patron of the arts.

I stayed with the enigmatic Mendelssohn who, upon meeting me, said, “So you’re the madman my sister has told me about!” My reputation precedes me, it seemed. We spent a tantamount of time together, where Mendelssohn at one point arranged a special concert of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra just for me.

Later, he requested I play some music for him, and upon finishing, Mendelssohn said I was worthy of being signed by Luigi Cherubini. “Words like this from such a master are a true honor, and one wears them with more pride than any ribbon.”

Religion Draws Charles Gounod to Study for the Priesthood

In 1843, at the age of twenty-five, my scholarship came to an end. I returned to Paris, where I took up a position carefully arranged by my mother as chapel master of the church of the Mission Entrangeres. The job was not what I had expected it to be, and I started losing the enjoyment of playing music.

The organ I was expected to play was cheap, the choir in shambles, and I knew, at that point, I was worth more than what I had been offered. I wanted to improve church music, turn it into something people enjoyed to listen: “It is high time the flag of the liturgical art took the place occupied hitherto in our churches by that of profane melody. Let us banish all the romantic lollipops and saccharine porosities which have been ruining our taste for so long. Palestrina and Bach are the musical Fathers of the Church: our business is to prove ourselves loyal sons of theirs.”

I believed one way to do this was to become a priest, and for a while, I studied at St. Sulpice, but unfortunately, my call to music was more compelling than the one to religion. After abandoning the orders, in 1850, I met with Pauline Viardot. Up until we met, I had concentrated solely on religious music and texts, but something was gnawing at me. I wanted more. The opera singer begged me to write an opera for her, and finding a door opening, I agreed.

Image: Opera singer, Pauline Viardot

Charles Gounod Composes his Contraversal Opera Sapho

Yet, I had no libretto. Speaking to Viardot, she arranged for Emile Augier to write the poem. He agreed on the condition that Viardot sang the lead. Sapho met resistance almost right away.

As soon as I had signed the contract, my brother died. He had become gravely ill in a short amount of time, and he had left a pregnant widow and a two-year-old child behind. Feeling responsible for them, I took a month off, concentrating on helping the family get back on their feet. Viardot rallied the troops and even asked Ivan Turgenev, a Russian poet, to join me on a retreat to Brie as a companion and offer comfort if needed.

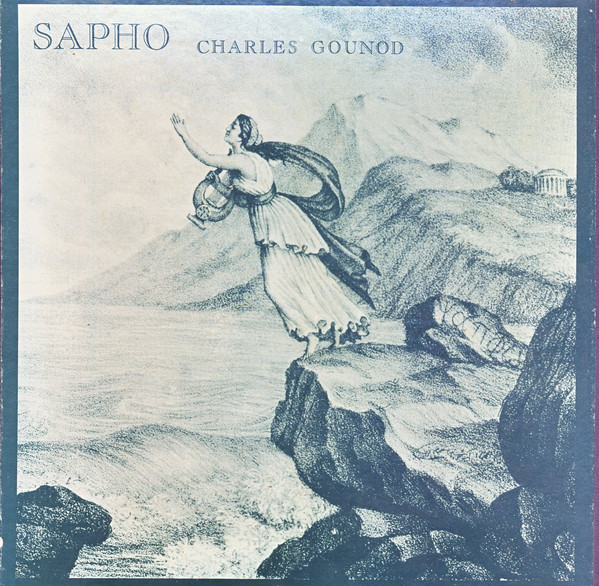

Image: Album cover of the opera Sapho, by Charles Gounod

He responded with a letter; “What Gounod lacks somewhat is a brilliant and popular side. His music is like a temple: it is not open to all. I also believe that from his first appearance he will have enthusiastic admirers and great prestige as a musician with the general public; but fickle popularity, of the sort that stirs and leaps like a Bacchante, will never throw its arms around his neck. I even think that he will always hold it in disdain. His melancholy, so original in its simplicity and to which in the end one becomes so attached, does not have striking features that leave a mark upon the listener; he does not prick or arouse the listener — he does not titillate him. He possesses a wide range of colors on his palette but everything he writes — even a drinking song such as Trinquons — bears a loft stamp.

He idealized everything he touches but in so doing he leaves the crowd behind. Yet among that mass of talented composers who are witty in a vulgar sort of way, intelligible not because of their clarity but because of their triviality, the appearance of a musical personality such as Gounod’s is so rare that one cannot welcome him heartily enough. We spoke about these matters this morning. He knows himself as well as any man knows himself. I also do not think that he has much of a comic streak; Goethe once said ‘man ist am Ende… was man ist.’”

I finished the music for Sapho by September, and rehearsals began in February 1851. It almost immediately met resistance with the censors, and some parts had to be re-written and re-worked. With politics and nerves as high strung as they were, it was no surprise that when the opera finally premiered on April 16th, 1851, it did not do as well as we had hoped. It lasted only a few runs, as Viardot had other engagements to keep up, and Sapho was quickly forgotten, even though the feedback it received was not bad.

Hector Berlioz himself had written: “For me, Sapho’s unhappy love and that other obsessive love of Glycera’s and Phaon’s error, Alcaeus’ unavailing enthusiasm, the dreams of liberty that culminate in exile, the Olympic festival and the worship of art by an entire people, the admirable final scene in which the dying Sapho returns for a moment to life and hears on one side the last distant farewell of Phaon to the Lesbian shore and one another the joyous song of a shepherd awaiting his young mistress, and the bleak wilderness, the deep sea, moaning for its prey, in which that immense love will find a worthy tomb, and then the beautiful Greek scenery, the fine costumes and elegant buildings, the noble ceremonies combining gravity and grace – all this, I confess, touches me to the heart, exalts the mind, excites and disturbs and enchants me more than I can say.”

Of me, Berlioz said, “… A young man richly endowed with noble aspirations; one to whom every encouragement should be given at a time when musical taste is so vitiated.” Unfortunately, even Berlioz’s high praise could not stop Sapho from closing after only nine performances.

Charles Gounod’s Marriage and Affair

In 1851, I married Anna Zimmerman. Before, I had been a regular guest in the Zimmerman household, joining the salons on an almost weekly basis. Unfortunately for myself, I had always been a hopeless flirt, and the Zimmerman daughters were no exception.

Even worse, I was compromised quickly and was told to either propose or leave them alone. That is how I found myself engaged to Anna. After receiving the ultimatum, I had been prepared to break it off, but somehow Madame Zimmerman, believing I had gone to the house to propose, was ecstatic at the thought. So I married Anna and never once set the record straight.

Image: Sketch drawing of a portrait of Anna Gounod, composer Charles Gounod’s wife

She was, of course, enraged after She had sent a beautiful bracelet as a wedding gift, and I had passed it off as my gift. She wrote, “The heart which Gounod talked about so much proved nothing but a bag of selfishness, vanity, and calculation.”

Although we had two children together, my wife was never at the forefront of my mind, whether in career choices or financial decisions. A stipulation that came with marrying Anna, and receiving her dowry, was that I ended all contracts and relationships with Pauline Viardot.

Marrying into the Zimmerman family came with its positives. Under their instruction, I became the conductor of the Orpheon Society in Paris. Also, I took on a substitute teaching position whenever my father-in-law could not make it himself. It was then that I met Georges Bizet, and the two of us created a lifelong bond only a teacher-student relationship could have.

Charles Gounod’s Bloody Nun Opera

The Zimmermans also financed many of my works, including the incidental music for Ulysse for the Comedie-Francaise and The Bloody Nun.

Set to the libretto by Eugene Scribe and Germain Delavigne, I wrote The Bloody Nun over two years between masses, completing it in 1854. It is a gothic tragedy, where a bloodied nun haunts Moldaw’s castle, and the two main characters, Agnes and Rodolphe, are forever forced to be star-crossed as their families are permanently at war with each other.

Unfortunately, the Bloody Nun was another opera that, although it seemed to be well received to start with, tanked quickly. After Nestor Roqueplan, the director of the Paris Opera, lost his position, no other opera was willing to take the risk and stage La Nonne Sanglante. It was labeled as ‘filthy’ and quickly disappeared from circulation.

The Doctor In Spite of Himself & The Legion of Honour for Charles Gounod

In 1856, I received the knighthood of the Legion of Honour, and my wife and I welcomed our first child, Jean. Shortly after, in 1858, I began working on another opera: The Doctor In Spite of Himself. Set to the libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carre, The Doctor was a comedy, the stark opposite to The Bloody Nun. Again, I faced numerous obstacles, with the Comedie-Francaise attempting to block the opera from being performed multiple times. Later, Erik Satie reworked the spoken dialogue into music.

Charles Gounod’s Best Known Opera: Faust

Faust is, more likely, the opera I am most well known for. Although it failed terribly at first, with no publisher willing to take it on, a small, up-and-coming company decided to take a chance. It was successfully revived in 1869 after I replaced the dialogue with recitatives. The revival also included ballets interspersed into the piece.

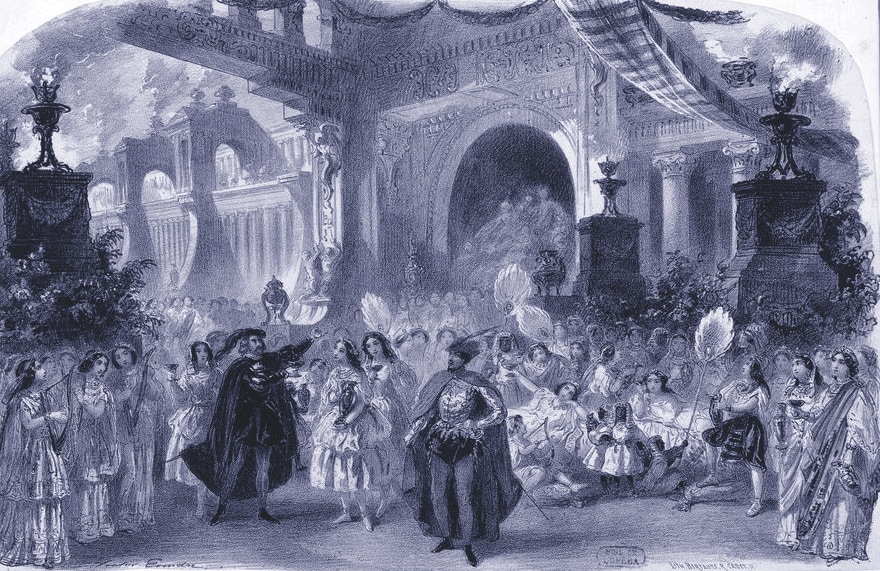

Image: Painting of the opera, Faust, by composer Gounod

Over forty years, the opera was performed over a thousand times, and its success later in England validated by Queen Victoria herself, who loved it so much she asked for the music to be played as she lay dying. Wallace Brockway said, “With few exceptions… the familiar numbers in Faust (and there are many) have the crushing sweetness of salon music… Much of the popularity of Faust has always depended upon the ease with which many of its tunes touch emotions that are universal. These are sentimentality, religiosity, vague aspirations… they pervade the score.”

Charles Gounod’s Opera: Romeo and Juliette

Faust’s late success urged me to write more operas. The following operas I worked on were Philemon et Baucis and The Dove – both in 1860 – and The Queen of Sheba in 1862, which was an abject failure in and of itself.

Romeo and Juliette, however, was better received than my previous three or four operas. It quickly became my second most famous opera, with Herbert F. Peyser saying, “Juliet’s waltz song, Romeo’s cavatina in the garden scene, the duets of the lovers, and the scene in the tomb” were the most notable pieces of music.

He continued with: “But even at their best, pages emphasize the composer’s weakness rather than his strength — the weakness of a lyricist who has said everything better once before.”

Image: Opera poster for Charles Gounod’s Romeo and Juliette

Charles Gounod Flees to England Due to the Franco-Prussian War

In 1870, during the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, I decided to move my family to England. There, I took up a small-time position at a publisher, writing music to bring a stable income. The Committee of the Annual International Exhibition commissioned me to write a piece for choir. After that success, Royal Albert Hall Choral Society elected me to a post as director.

Living in England, I had put a pause on writing operas, my life, instead of becoming influenced by Georgina Weldon, whom I met in 1871. She began to manage my career, taking a managerial role in discussing my pay or royalties.

Charles Gounod’s Relationship Upheavals – His Affair with Georgina Weldon

Georgina Weldon was a well-known singer. We had met at a concert in which I was performing, and our eyes met across a crowded room. Later, she wrote, “as if he were especially addressing himself to me. I did not know which way to look. My tears, which had begun to flow at the first line, had become a rivulet, the rivulet had become a stream, the stream a torrent, the torrent sobs, the sobs almost a fit!”

Of course, rumors quickly circulated about our relationship, especially when I moved into her home after an argument with my wife. She was married, too, but her husband, Harry, seemed perfectly fine with the arrangement. After Anna moved back to Paris, I stayed behind, attempting to continue composing while living with Georgina.

The singer did much for me, including founding a choir in my name and singing my music at most of her performances, but things turned terrible swiftly. Soon, we argued all the time, threats of murder or suicide and, later, a lengthy and painful lawsuit from Georgina. She refused to release my manuscripts and forced me to flee England, back to Paris, and back to my wife.

Image: Portrait of singer Georgina Weldon

A New Music Scene in France for Charles Gounod

However, returning to France meant becoming accustomed to a new musical scene. France’s music had evolved in my absence, and I was no longer the top composer of the country. With the rise of the Societe Nationale de Musique came a wave of budding, talented composers, one of which was Camille Saint-Saens. I dubbed him the “French Beethoven” and enjoyed his works immensely.

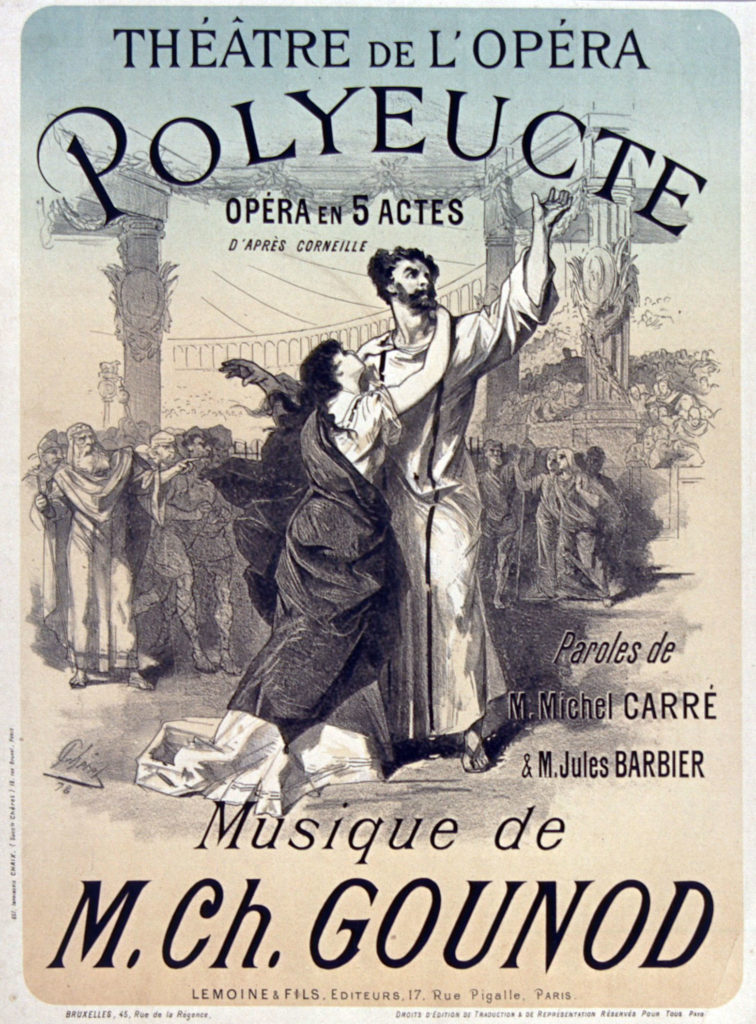

The opera I was working on at the time of my return was Polyeucte, based on the play by Pierre Corneille. I hoped to show “the unknown and irresistible powers that Christianity has spread among humanity” in this opera, but once again, obstacles stood in my way.

First, in 1873, a fire had ravaged the Paris Opera, and then later, in 1874, Georgina Weldon refused to release the only first draft that remained. After attempting to bring a lawsuit against her, I decided to re-draft from memory, which of course, took some time.

Image: Poster for the opera, Polyeucte, by composer Gounod

It finally premiered in October 1878 at the Palais Garnier. Unfortunately, it did not do well. I named Polyeucte “the sorrow of my life.” It lasted 29 performances.

Charles Gounod’s Last Opera: Le tribute de Zamora

My last opera was Le tribute de Zamora which premiered in 1881 at the Palais Garnier. It was highly successful, with encores begged from the audience. “I dreamt of the model… who was terrifying in satanic ugliness.” It was based on the libretto by Adolphe d’Ennery, and the opera reflected my entanglement with religion very well.

Charles Gounod’s most famous Instrumental: Funeral March of a Marionette

Following the story of a Marionette, who has died, the Funeral March of a Marionette follows a funeral procession. I had begun composing the piece while living in London and completed it in 1879. It was the very last musical piece, and it was orchestrated before my death.

After my passing, it became a very popular score. Funeral March of a Marionette has been used in movies and television and is best known as the theme of Alfred Hitchcock’s “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” program. From then on, Funeral March of a Marionette has been regularly used in television and movies.

Image: Album cover of Funeral March of the Marionette, by composer Charles Gounod

Charles Gounod Writes Religious Masses Prior to his Death

After Le tribute de Zamora, I concentrated on religious masses and ended up writing eleven of them between 1876 and 1893, ending the stint with a Requiem I unfortunately never completed. On October 15th, 1893, at age seventy-five, I suffered a stroke that sent me into a coma. After three days, I passed away at home. My body was buried in Auteuil.

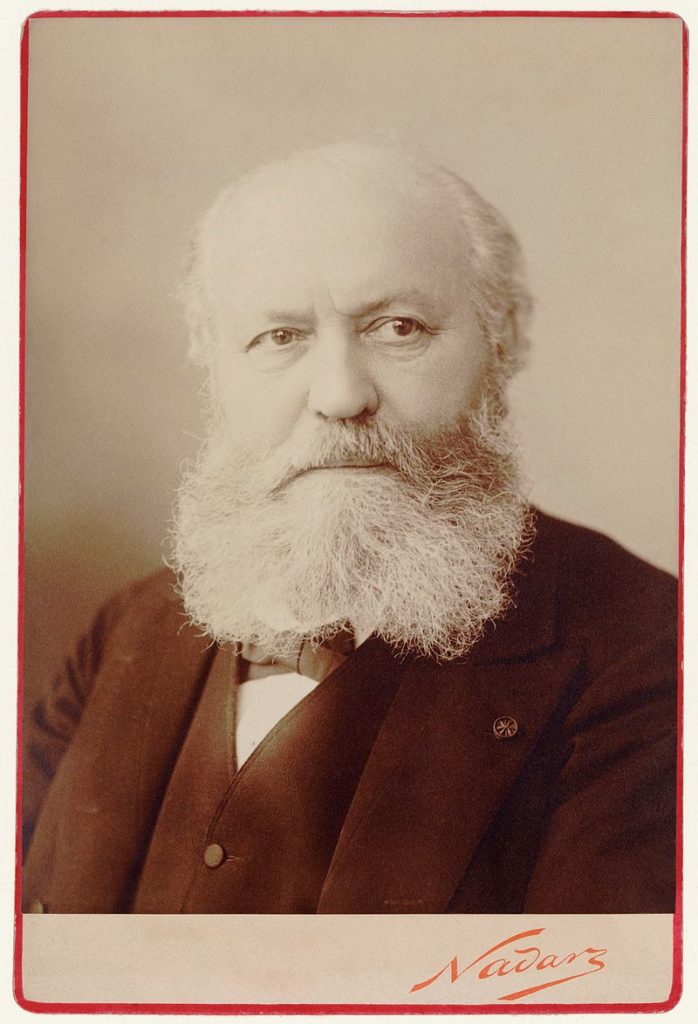

Image: Portrait photo of composer, Charles Gounod

Please find compelling quotes of Charles Gounod here on his quotes page.

Sources:

Great Composers 1300-1900 by David Ewen

Famous Composers by Nathan H. Dole

The Lives of Great Composers by Harold C. Shonberg

Charles Gounod Biography: https://www.charles-gounod.com/vi/bio/resume/index.htm

Charles Gounod (1818-1893): https://mahlerfoundation.org/mahler/contemporaries/charles-gounod/

“The Family is Excellent” Charles Gounod and Anna Zimmerman: https://interlude.hk/family-excellent-charles-gounod-anna-zimmerman/

Monsieur Gounod and Mrs Weldon: https://www.planethugill.com/2013/07/monsieur-gounod-and-mrs-weldon.html