Edvard Grieg’s Early Childhood and Musical Inclination

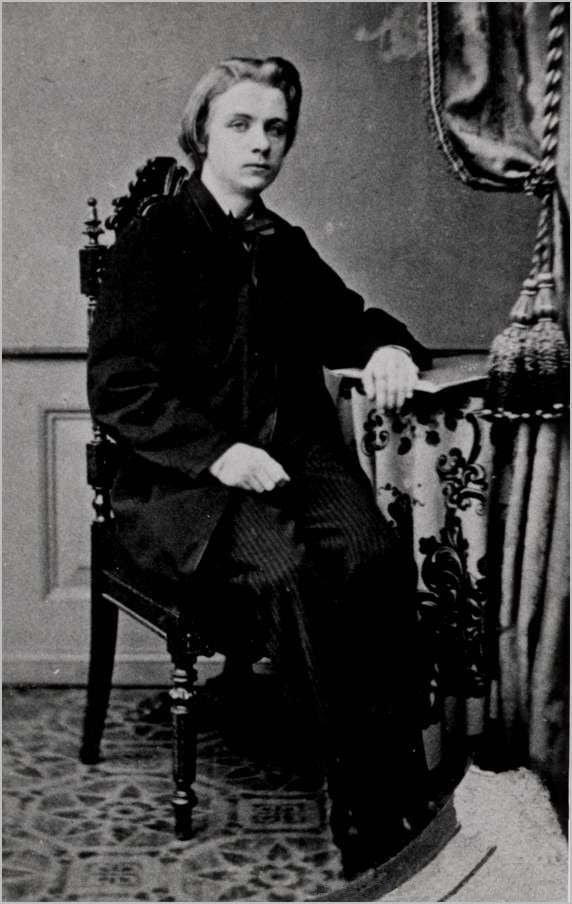

I was born in Bergen, Norway, in June, 1843. My family was rather musically inclined, with my mother being a music teacher and the daughter of Edvard Hagerup, for whom I was named after. My father worked as a merchant and consul in Bergen, but he, too, enjoyed music although he was not as well-versed as my brother. Both my brother, John, and I were encouraged to play and study music.

Mother was my first music teacher, and she began teaching me when I was six years old, after seeing how well I took to music. She taught me the basics before sending me to school at Tanks Upper Secondary, where I studied music more in-depth. Her dedication to my craft knew no bounds, and even when I thought she was not listening, she would surprise me by yelling the right note to play when I made a mistake.

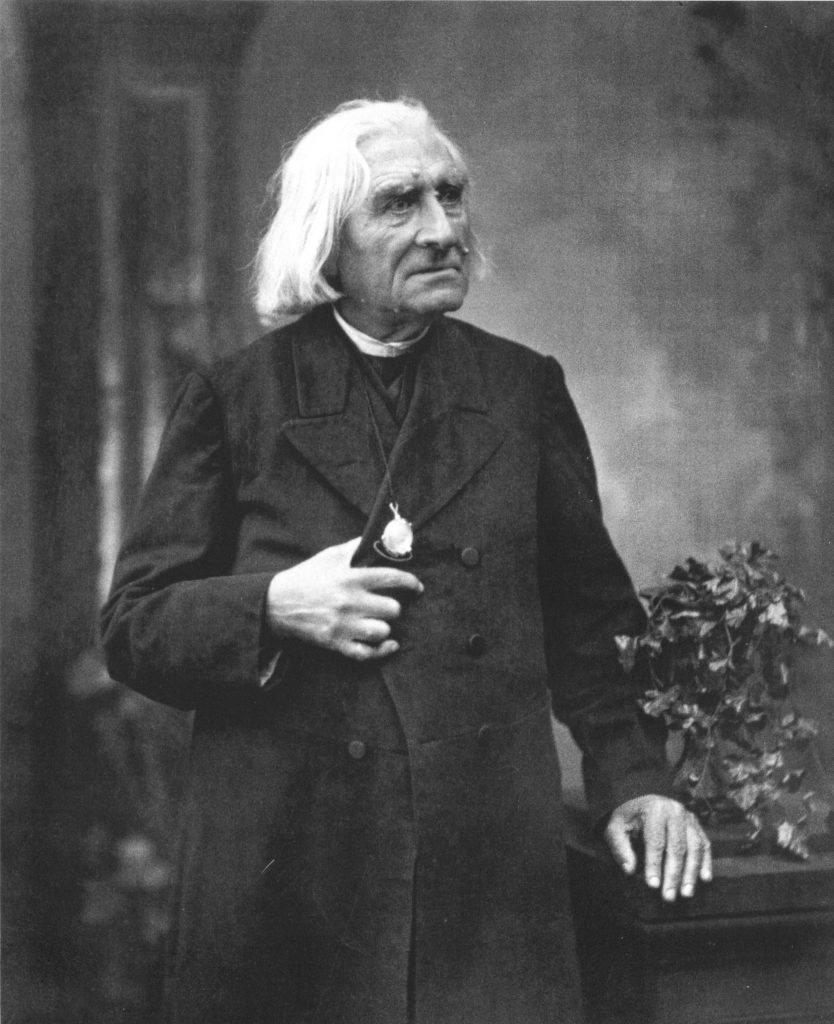

Image: A photograph of a young Edvard Grieg

School, however, was a nightmare. I did not enjoy the lessons, did not have any friends and struggled to fight the laziness.

“At that time, the school seemed to me nothing but an unmitigated nuisance; I could not understand in what respect all the torments connected with it were to a child’s advantage and even today I have not the least doubt that that school developed only what was bad in me and left the good untouched.”

I wasn’t overly interested in learning and found myself to be quite lazy. It was something that had plagued me since a young child, and at Tanks I was often bribed with rewards in order to create some sort of feeling of ambition within me. I was very fond of skipping class, often pushing the rules so I could be sent home. In fact, I was well known to stand in the rain until I was soaked through, knowing I would be sent home rather than left to sit in class soaking wet.

One day, though, I was unlucky in my plans. I had showed up to class wet through, but there was no sign of rain outside. Rather than sending me home, I was made to sit through classes until dry. It’s very possible that this was the cause of later afflictions in my lungs.

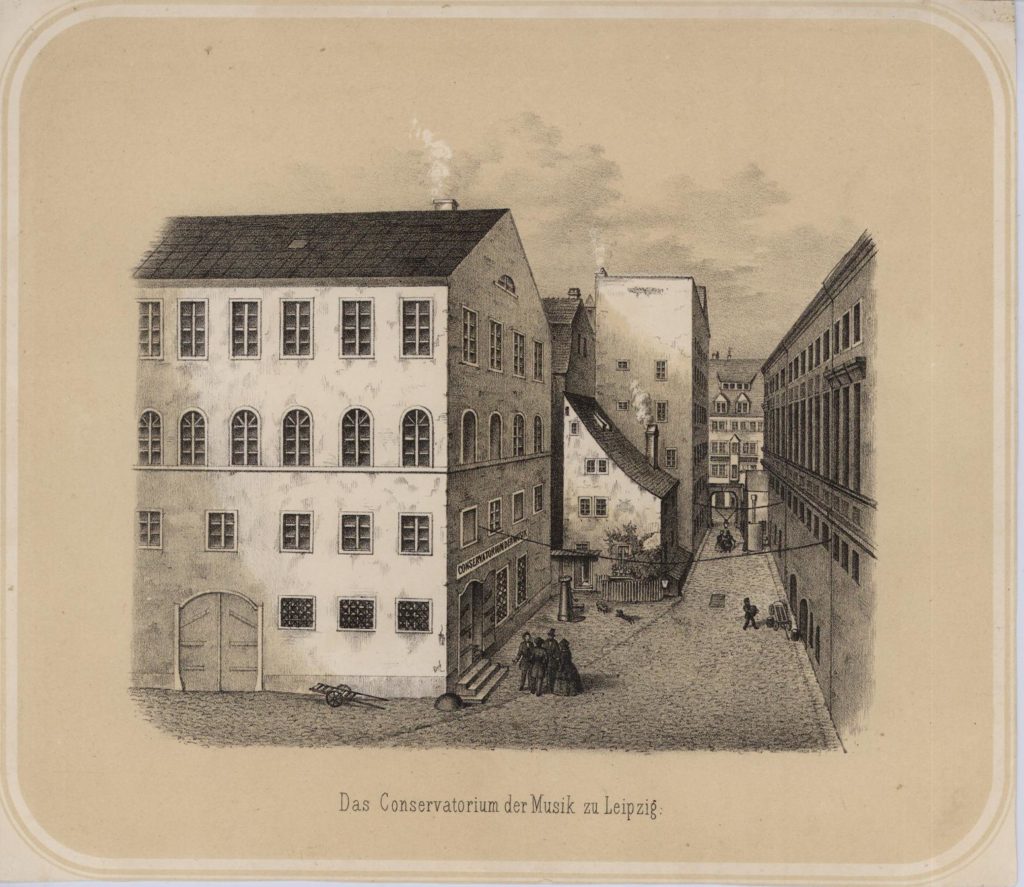

At fifteen years old, in 1858, an old family friend, violinist Ole Bull, recognized my talent and convinced my parents to send me to the Leipzig Conservatory, in Germany. There, I would learn about music in all its shapes and forms, and how to nurture my talent.

Edvard Grieg Joining the Leipzig Conservatory

After my parents agreed, I joined the Conservatory. While there, I mainly concentrated on my piano studies, finding the other classes and courses tedious. “I must admit, unlike Svendsen, that I left Leipzig Conservatory just as stupid as I entered it. Naturally, I did learn something there, but my individuality was still a closed book to me.”

Arriving at the Conservatory was a new, fresh start for myself. Although terribly homesick at first, I wanted to be “a wizard in the realm of music.” The work was hard, and the teachers harder. One particular teacher of mine, Louis Plaidy, was incredibly difficult to learn from. He liked things done his way, and there were no other options.

Image: Drawing of the Leipzig Conservatory

I tried for a long time to follow Plaidy’s teachings, but one day I couldn’t stand it any longer. “The next morning at nine o’clock I knocked at the Director’s door and was admitted. Without further preface I uttered what was in my heart. I told him how inconsiderate and insulting his behaviour toward us had been, since he treated us all alike, and as far as I was concerned I was determined not to put up with it. He flew into a frightful rage, leaped to his feet, and showed me the door. But I was in a fighting mood. ‘Certainly I will go, Sir, but not before I have said what I came to say.’ And now an astonishing thing happened: Sehleinitz suddenly came down from his high horse. He walked over to me, tapped me on the shoulder and said in a voice as soft as a sucking dove: ‘Well, it is fine of you to stand up for your dignity.’”

After that, I was able to switch classes and the Director and I became good friends. In fact, I became quite good friends with many people, unlike when I studied at Tanks. One of my friends was a friend of a professor whom I did not like. His name was Moritz Hauptmann, and I had played him one of my own compositions — unknowingly. He had been in the same room as I.

“When I had played it through and was about to leave the piano, I saw to my astonishment an old gentleman get up from the professor’s table and come to me. He laid his hand on my shoulder and said: “How are you my boy? We must be friends.”” Hauptmann would often spend his evenings poring over my notebooks, reading my half-written compositions.

At the end of my time at the Conservatory, I ended up majoring in piano and minored in the organ. However, while at the Conservatory in 1860, I became quite ill. I suffered terribly with both pleurisy and tuberculosis, and although I survived, I never completely recovered. Forever since, one of my lungs was damaged and it affected my life almost every day. I blame this early illness for my untimely death.

Also In 1860, when I was seventeen years old, I debuted in Karlshamn, Sweden as a concert pianist. When I graduated from the Conservatory in 1862, at nineteen years old, I returned home to hold a private concert where I played Beethoven’s Pathetique.

Grieg Leaving the Conservatory

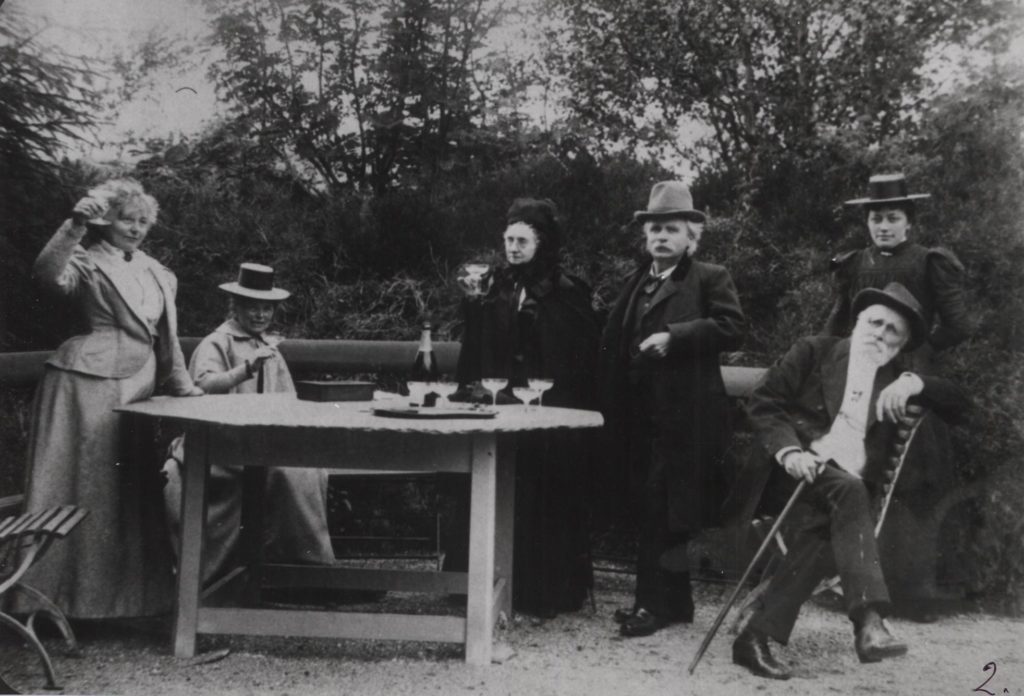

After my graduation performance, I decided to move to Copenhagen, Denmark, where I lived for three years. While there, I met my good friend Rikard Nordraak, as well as Niels Gade and J.P.E Hartmann. It was Niels Gade who persuaded me to write my own symphony, which I did, but it never saw the light of day. I always felt like my work was not good enough, and it was Rikard Nordraak who helped me out of that state of mind.

Image: Photograph of Edvard Grieg and his friends sitting outside at a table celebrating with champagne

“I had found myself… and with the greatest facility I overcame all the difficulties which in Leipzig had seemed to me insurmountable. With my fancy emancipated I composed one work after another. That my music at first was criticized as artificial and strange did not confuse me; I knew what I wanted and I boldly aimed for the goal which I meant to attain.”

These friendships inspired me and pushed me to be more than I had been. It was Rikard and Gade who helped me see the beauty and magic in Norwegian folklore and fairy tales, and thanks to them, I composed my first Piano Sonata in E and a Violin Sonata that I then dedicated to Gade.

When Rikard passed away in 1866, I composed a funeral march for him, the same one I later requested to be played at my own funeral. It was thanks to the funeral march that my work became more recognized.

Edvard Grieg’s Marriage and Family

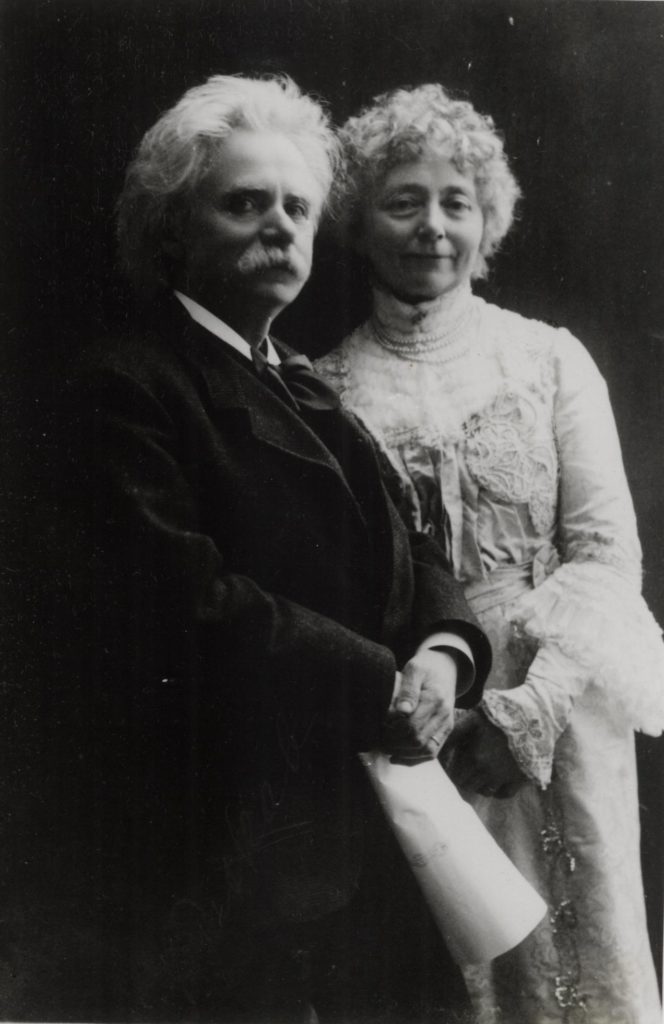

In 1867, at twenty-four years old, I married my first cousin Nina Hagerup. Nina was a lyric-soprano, and we would often perform concerts together, such as the private concert for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in 1897.

Our engagement was greatly opposed by her mother and father, and I was made to prove myself by holding concerts and earning money. Nina encouraged me to write more and more, and my output of work increased dramatically. I was no longer the lazy student I had been, but a hard working musician making a living. Once I had proved myself, I became good friends with her family.

We had a daughter together, Alexandra, who was born in 1868. Unfortunately, she passed away in 1869 from meningitis. We never tried for children again.

Image: Photograph of Edvard Grieg and his wife Nina

Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto A Minor

During the years of 1867 and 1869, I composed my Piano Concerto A Minor while visiting Denmark on holiday. I had begun to use the inspiration of folklore and landscapes to compose music, and Denmark was a rather large source of inspiration. It debuted on April 3, 1869, in the Casino Theatre in Copenhagen. Although I couldn’t debut it myself due to commitments in Oslo, it was played by Edmund Neupert, a famous, and composer.

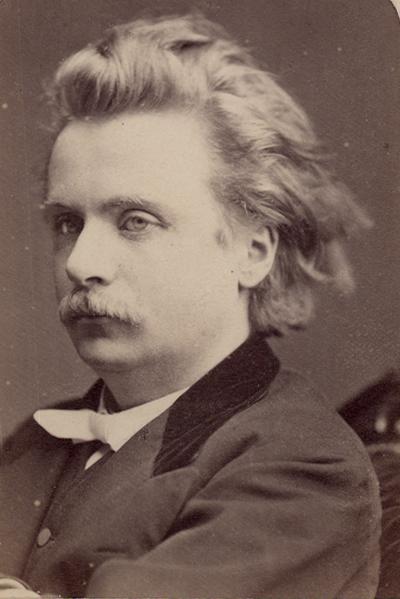

In 1868, at twenty-five years old, I met Franz Liszt. We had been corresponding before our meeting, and he had written a recommendation to the Norwegian Ministry of Recommendation, who gave me a travel grant. In his first letter to me, Liszt had congratulated me on my violin sonata, writing: “It evidences a powerful, logically creative, ingenious, excellently constructive talent for composition, which needs only to follow its natural development to attain high rank. I could hope that you are finding in your own country the successes and encouragement you deserve; you will not fail them elsewhere.”

Image: Photograph of composer Franz Liszt

Liszt and I met in person in Rome in 1870, where I played my violin sonata for him. Meeting him had been the “best two hours of my life.” We had discussed my music, and he had also played for me, making it an unforgettable experience.

The second time I visited him, Liszt taught me and gave me advice on orchestration. I adopted some of his teachings and advice. Liszt’s was a treasured friendship I had never expected. He pushed and encouraged me, telling me I could do anything. “Go on in this way; I assure you, you have the stuff for it and– don’t be frightened away.” I always remembered his words in my hardest moments.

Edvard Grieg’s Play, Peer Gynt

I am probably most well known for my incidental music for the play Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen. The play is loosely based on the fairytale but is rooted more in fact than fiction. It was a difficult play to write music for. “It progresses slowly… and there is no possibility of having it finished by autumn. It is a terribly unmanageable subject.”

However, the more I worked on Peer Gynt, the more I became involved in the story. My wife once said, “The more he saturated his mind with the powerful poem, the more clearly he saw that he was the right man for a work of such witchery and so permeated with the Norwegian spirit.” She was right. Once I found my flow, I managed to complete the music in the autumn of 1875, as agreed.

Image: Drawing of the play Peer Gynt

Although its premiere was successful, I felt as if “I was thus compelled to do patchwork… In no case had Ithe opportunity to write as I wanted… Hence the brevity of the pieces.” The management of the theatre had been so specific with the duration of each suite, and how many, that it left no room for creativity.

I managed to rework some of the music when Peer Gynt was later revived in 1885. I added new pieces, reworked some of the suites, and made them into what I had originally intentioned.

In 1880, when I was thirty-seven, I became the new Music Director for the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra. I had affiliated myself with them before the release of Peer Gynt, but thanks to its success and the popularity it brought me, I successfully received the new position at the Orchestra without disagreement.

Edvard Grieg’s Composition of Holberg Suite

In 1884, for the 200th anniversary of the birth of Ludvig Holberg, I composed the Holberg Suite. I had originally composed the suite for piano, but later decided to rework it for orchestra. As most of my music up until then, it was inspired by Norway: its mountains and folk music a never ending inspiration. There was also an element of inspiration from 18th century French and Italian music, lending it a Baroque style that differentiated it from my usual works.

Image: Painting portrait of Holberg Roed

New Friendships: Grieg and Tchaikovsky

Nina and I ended up making Bergen our home, and our house, Troldhaugen, is now a museum as part of my legacy. In January 1888, when I was forty-five, I met Tchaikovsky. We both admired each other’s music and became good friends. Nina and I would invite Tchaikovsky and his wife, Anna Brodsky, to our home and vice versa. Our meetings would happen often.

After our meeting in January, I had sent him a letter praising his Suite No. 1. He had said that my praise was the source of “the most precious joy that can fall to the lot of an artist.” We would correspond often, especially when we would not be able to see each other, and especially so after one of us had a concert. I remember writing to Tchaikovsky, “You cannot imagine what hoy my meeting with you had given me. No, not joy, but much more! You have left such a strong impression on me both as an artist and as a human being.” He was a large influence on me, and his friendship and admiration incredibly precious, something I treasured.

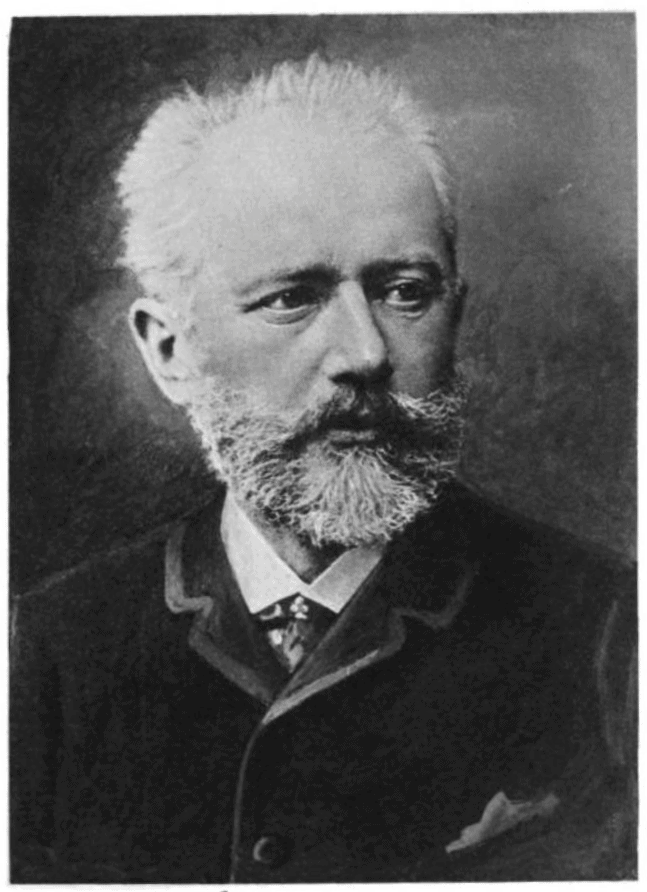

Image: Photograph of Composer Tchaikovsky

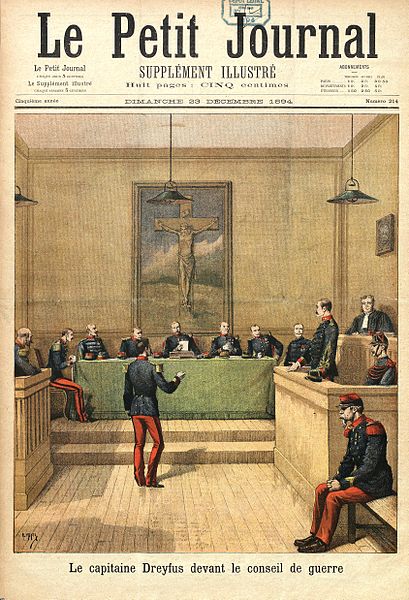

The Dreyfus Affair and Edvard Grieg

In 1894, when I was fifty-one, I great miscarriage of justice began what is now called the Dreyfus Affair. A French artillery officer of Jewish descent was convicted to life imprisonment for allegedly spying on French military for the German Embassy. In 1896, it was proved it was not the artillery officer, Alfred Dreyfus, but a French Army major named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. Unfortunately, the scandal did not end there, and Dreyfus was later convicted for yet another decade.

At the time of the scandal, I had been invited to hold a concert in France, where I would play in Edouard Colonne’s orchestra. The injustice Dreyfus faced incensed me, and I canceled all of my concerts, declining Colonne’s invitation with a letter. I hoped France would “soon return to the spirit of 1789 when the French republic declared that it would defend basic human rights.”

Image: Drawing on the front of a journal depicting the trail of the Dryfus Affair

The letter was published, and my stance in the scandal made me the subject of hate mail, death, and more. I refused to visit Paris or France for a good number of years.

Grieg’s Retirement, Death and Legacy

As I aged, my health deteriorated more and more. In 1903, at sixty years old, I retired. I made nine recordings on a gramophone of my piano music. Three years later, in 1906, I met pianist Percy Grainger in London. He blew me away with his talent, and I remember saying, “I have written Norwegian Peasant Dances that no one in my country can play, and here comes this Australian who plays them as they ought to be played! He is a genius that we Scandinavians cannot do other than love.”

During my retirement, I was also awarded two honorary doctorates by the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford.

Image: Portrait photograph of Edvard Grieg

By the time Grainger and I met, I was severely unwell. We were both at dinner, and I was taken by Grainger’s enthusiasm for all of my music, including some of my lesser-known pieces. We became good friends, and the two of us spent a week together at my home, Troldhaugen, the next summer. We spent the week rehearsing for my performance in Leeds that October, but unfortunately, the day I was due to leave for England, I died of heart failure.

It was September 1907, and I was only sixty-four years old. My last words were, “Well, if it must be so.” As requested, the funeral march I had composed for Rikard Nordraak was played, as well as the funeral march from Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2. Thousands of people honored me in the streets, and I was cremated and interred in a mountain crypt near my home where Nina would join me later on.

I bequeathed all of my property to the promotion of music in Bergen.

Please find compelling quotes of Edvard Grieg here on his quotes page.

SOURCES:

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edvard-Grieg

- https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/edvard-grieg-462.php

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edvard_Grieg

- http://greatcomposers.nifc.pl/en/grieg/catalogs/places/282_leipzig-conservatory

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peer_Gynt_(Grieg)

- https://www.classicfm.com/composers/grieg/guides/story-behind-griegs-peer-gynt/

- http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Edvard_Grieg

- http://greatcomposers.nifc.pl/en/grieg/catalogs/places/515_paris

- https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2010/january/1290491284/shane-maloney/percy-grainger-edvard-grieg#mtr

- Great Composers 1300-1900 by David Ewen

- Famous Composers by Nathan Haskell Dole