Bedrich Smetana’s Early Life as a Musical Prodigy

I was the 3rd child born on March 2, 1824, into a large, musically inclined family. My father, a violinist in a string quartet, had been previously married twice before meeting my mother, a dancer. Before my birth, my father had been a brewer, and during the Napoleonic Wars, had amassed a small fortune. He began teaching me the piano and violin while I was still very young.

Musically inclined from a young age, I studied both piano and violin. I took part in performing a Haydn quartet when only five years old. Later, I would tell Liszt, “I wanted to become a Mozart in composition and Liszt in technique.”

Although my parents were not keen on supporting a musical career, I gravitated quickly towards composition. “When I was seventeen years old, I did not know C sharp from D flat. Ignorant of this, yet I wrote music.”

At eight years old, I wrote folk music and dance numbers, but my father was not supportive. He wanted me to concentrate on my studies and go on to have a well-paying career.

Unfortunately, school life was not easy. I was regularly homesick when I attended the gymnasium and bullied and picked on by classmates for dressing below their standards. I periodically skipped classes and attended concerts and recitals, sometimes avoiding school altogether. When my father found out, he was furious and moved me as far away from the city as he could.

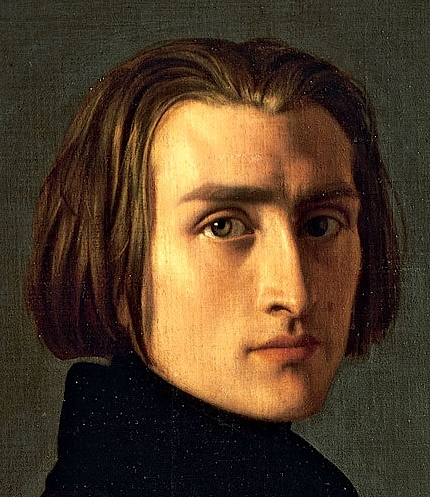

Image: Painting of Bedrich Smetana

Bedrich Smetana’s Romances & Growing Popularity

When Josef Smetana, a cousin, heard of my plight, he offered to introduce me to the Premonstratensian School in Pilsen, where I could hone my skills as a pianist. My father reluctantly agreed, and I later graduated in 1843 at the age of nineteen.

During and after my time at the school, I was well known for my piano skills and was in high demand at parties and soirées. Regularly, I would accept invitations to play in different homes and at various events, securing a clientele that paid handsomely for my services.

My busy social life enabled me to meet my future wife, Katrina Kolarova. An accomplished pianist herself, she became my musical and romantic partner. Later on, we both formed the Piano Institute, a music school that proved to be of value to students and provided us with financial success.

I fell deeply, deeply in love with her. She inspired me to compose, and each successive piece I dedicated to her. “When I am not with her, I am sitting on hot coals and have no peace.”

Image: Photo of Katerina Kolarova, Smetana’s first wife

After Smetana Returns to Prague to Study Music Composition and Teach, He Meets Franz Liszt & Hector Berlioz

In August of 1843, I left for Prague, returning to my city full of hope. I left with only twenty guldens, and no real idea of what I was going to do for work, but only knowing that I had to return, that my fortune lay in Prague.

In 1844, Katerina’s mother introduced me to Josef Proksch at the Prague Music Institute, and I began taking lessons in composition from him. I also began teaching Count Thun’s children. As my financial difficulties eased, Josef then introduced me to Franz Liszt and Hector Berlioz at an event.

Meeting Liszt was like a dream come true. His compositions heavily influenced my early music, and I had always seen him as an idol. Liszt became an excellent friend, and ours was a friendship that lasted my entire life.

In 1848, I wrote to Liszt for financial aid and to help me find a publisher for Six Characteristic Pieces. Although he never loaned me money, he wholeheartedly supported my idea of opening the Piano Institute and became a regular visitor to the students.

Image: Portrait painting of a young Franz Liszt

Bedrich Smetana’s Failed Piano Performance Tour

In June 1847, I resigned from my tutoring position. Instead, I decided to tour Western Bohemia in the hopes that my popularity as a pianist during my school years would follow me into a wider area.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. I had very little support, and when the Prague Revolution began in 1848, I returned home to take up my part.

Bedrich Smetana Becomes a Czech Revolutionary

While tutoring private pupils, I also wrote patriotic articles and nationalistic music, such as The Song of Freedom. It incited good morale in the people, but unfortunately, the revolution failed.

Once Austria attacked Prague, I helped build the barricades, but a much stronger army quickly stopped us. I then met Karel Sabina, another person who would become a good, close friend.

A year after the opening of the Institute, I finally married Katrina — August 27, 1849. We had four daughters together, and we left Prague to move to Sweden after the revolution, where I worked as a teacher and conductor for the Goteborg Orchestra.

Image: Photo of Karel Sabina, Czech writer

Terrible Tragedies Strike Bedrich Smetana’s Family

In 1850, I accepted a position as a court pianist at Prague Castle. It was then that I began dedicating myself more to composition. During my time at the castle, I composed Triumphal Symphony for the commemoration of Emperor Franz Joseph’s wedding, but those in charge of the event rejected my symphony.

Refusing to take no as an answer, I was not ready to let my work go to waste, and so I hired, out of my pocket, an orchestra to play the piece at Korvit Hall in Prague on February 26, 1855.

It was also during that time, between 1854 and 1856, that tragedy befell my family. We lost three of our daughters to tuberculosis, and scarlet fever and, shortly after, Katerina was also diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Prague’s dark political climate was contributing terribly to my mental health, and I grew disenchanted with the city of my heart. “Prague did not wish to acknowledge me, so I left it.”

Image: Photograph of Prague Castle in Prague, Czech Republic

Bedrich Smetana Moves to Sweden, Takes on a Lover & Loses his Wife

We — Katerina, myself, and our daughter Zofie — moved to Sweden, traveling specifically to Gothenburg, where I became the new conductor of the Gothenburg Society for Classical Choral Music.

Gothenburg was a blank canvas, their music scene very backwater and easily modded. I opened a music school there, too, that was quickly drowning in applications from eager young students.

I traveled to Weimar to visit with Liszt, who inspired me to compose again. At that time, I met a young woman named Frojda Benecke, who became my muse and mistress. Suddenly, I could not stop sketching! Unfortunately, none of my sketches became completed pieces.

Katerina died on April 19, 1859. She passed “gently without our knowing anything until the quiet drew my attention to her.” After securing someone to watch Zofie, I visited with Liszt again, his company desperately needed in my time of mourning.

New Success in Opera for Bedrich Smetana in Prague

I remarried a year later, to Barbora Ferdinandiova. I began thinking of Prague again, finding Gothenburg lackluster in comparison. “My home has rooted itself in my heart so much that only there do I find real contentment. It is to this I will sacrifice myself.” The decision was easy to make — we returned to Prague.

In 1861, the news announced that the Provisional Theatre was coming imminently. I realized that this was the perfect opportunity to write operas reflecting the Czech national character — and I wanted to be the person that wrote them!

The Provisional Theatre’s rejection of me for the position of director did not deter me. With help from my old friend Karel Sabina, who gave me his librettos, I entered a competition in which I was to compose an opera based on Czech culture and history. This piece later became The Brandenburgers in Bohemia.

Image: Photo of Barbora Ferdinandiova, Smetana’s second wife

Bedrich Smetana’s Opera, The Brandenburgers in Bohemia

Based on the libretto by Karel Sabina, The Brandenburgers in Bohemia tells the story of the Brandenburgers occupying Bohemia and their ruling over five years.

It was composed during a patriotic time and very well received at its premiere at the Provisional Theatre on January 5, 1866. Austria and Prussia’s relationship was strained at the time of the premiere, and soon after, war broke out.

The Brandenburgers in Bohemia also won the competition I had entered back in 1861, and its previous performances only increased the positive responses I received on the piece. The Provisional Theatre sold out all the seats, and the press had a field day, as my work reflected the times.

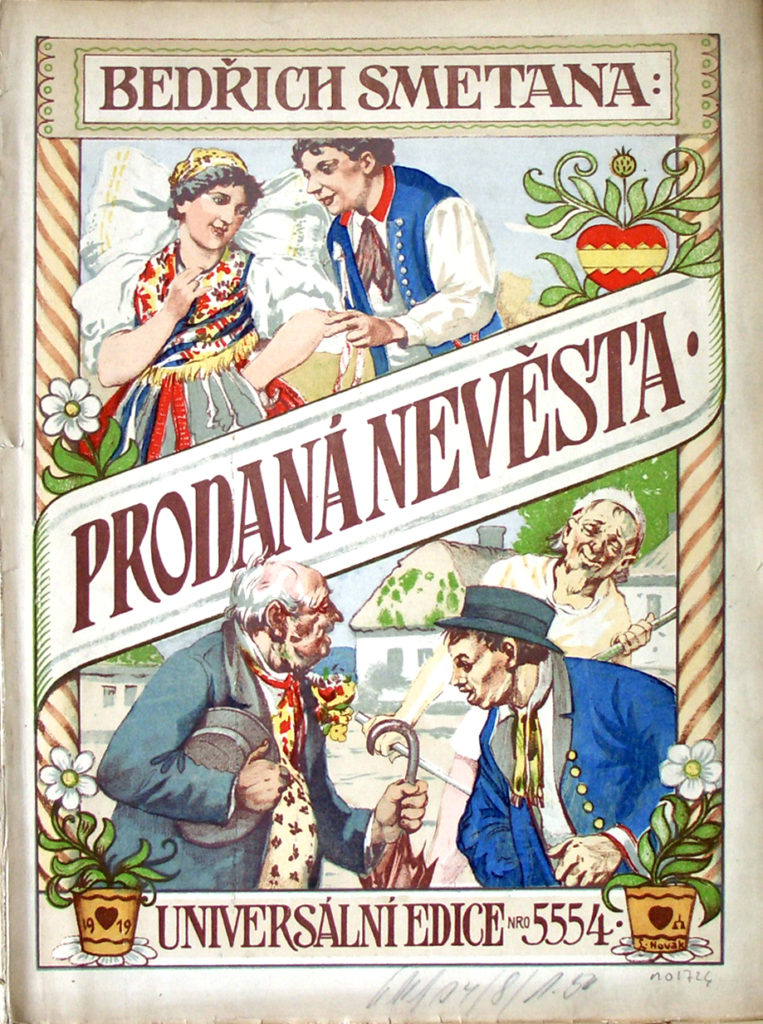

Smetana Composes His Most Memorable Opera, The Bartered Bride

In the same year, I also composed The Bartered Bride, again based on a comedic libretto by Karel Sabina. It told the story of star-crossed lovers and true love triumphing over evil. “I composed it without ambition, straight off the reel, in a way that beat Offenbach himself hollow.”

It started as an operetta and was not immediately successful. I expanded it two different times before it

When I initially composed the work, The Bartered Bride did not have the same immediate success that The Brandenburgers had enjoyed. After two significant revisions with an expansion of the work into a full opera and a new premier in 1870, it quickly gained popularity. It also made an enormous contribution to Czech music and its growing popularity. In your time, The Bartered Bride is my most well known musical composition.

Critics said, “Smetana’s debt to his own national music was of the best kind, unconscious. He did not, indeed, ‘borrow’, he carried on an age-long tradition, not of set purpose, but because he could no more avoid speaking his own musical language than he could help breathing his native air.”

Image: Poster for, “The Bartered Bride,” Smetana’s opera

Smetana Enjoys a Financially Successful Time as a Conductor

1866 was a fruitful year. After completing two different operas successfully, the Provisional Theatre installed me as their conductor. However, the job did not come without its downsides.

Becoming conductor meant I quickly made enemies, unintentionally, with the Prague School director for Singing and even within the theatre itself. A petition began making the rounds where people were calling for my dismissal, and Frantisek Pivoda slated my refusal to use his students in our productions.

The Provisional Theatre promptly dismissed me, although they later reinstated me in 1873, and I received better pay and held more significant power. But the price I paid for all of the relentless attacks caused a decline in health. “Czech opera sickens to death at least once annually,” a critic once said.

Image: Painting of Smetana playing piano while friends watch on

Smetana Loses His Hearing While Composing his Opera Libuse

In 1872, I began work on Libuse, a three-act festival opera based on Josef Wenzig’s libretto. I channeled all my energy into finishing it in time for the National Theatre’s opening in 1881.

But my work did not distract me enough from attacks by my critics. The stress from those attacks contributed to becoming “…ill as a result of nervous strain caused by certain people recently.” In the summer of 1874, at fifty years old, I became quite unwell with a rash and sore throat.

The subsequent block to my ears did not relent after the sickness had passed. “The ear is quite healthy externally. But the inner apparatus — the admirable keyboard of our inner organ — is damaged, out of tune. The hammers have got stuck, and no tuner so far has succeeded in repairing the damage.”

Image: Photo of Prague’s National Theatre

Bedrich Smetana’s Depression, Worsening Health & Crumbling Marriage While Composing My Fatherland

I had no choice but to retire from the theatre. My ex-mistress and old friends raised money to send me abroad to receive the top medical help, but nothing worked. Depression fell like a curtain over me. At the time, I said, “If my disease is incurable, then I should prefer to be liberated from this life.”

My marriage crumbled as a consequence, but neither of us filed for divorce. We could not stand to be around each other anymore. “I cannot live under the same roof as a person who hates and persecutes me.”

Finally, in June 1876, I retired to my eldest daughter’s home to quietly compose and live in peace. There, I completed the last four movements of My Fatherland and attended the premiere of Libuse on June 11, 1881, to a very successful reception.

After that, my health deteriorated drastically. Within two years, I became utterly incoherent, and my mental health took a turn for the worse. I was increasingly violent and unable to speak; my family could no longer care for me, so I was sent to an asylum in April 1884 to receive professional care.

Bedrich Smetana’s Death & Musical Legacy

Unfortunately, I passed on May 12, 1884, and years later, it came to light that I died of syphilis, which had also caused dementia. The funeral was a procession through the streets of Prague, one last walk through my city. That night, the National Theatre performed The Bartered Bride in my honor.

My legacy includes eight operas and symphonic poems that inspire people, such as Ma Vlast. I composed chamber music, including compositions for piano, songs, the string quartet piece, From My Life, and string and string trio pieces.

I became known as the father of Czech music. My contribution to music-making contributed significantly to a national musical identity for Czechoslovakia. History has shown that I was the first composer to achieve international recognition by composing nationalistic music.

Image: Photograph of Smetana in older age

Please find compelling quotes of Bedrich Smetana here on his quotes page.

SOURCES

- Great Composers, 1300-1900 by David Ewen

- The Lives of Great Composers by Harold C. Shoenberg

- Fifty Famous Composers by Gervase Hughes

- Libuse: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libu%C5%A1e_(opera)

- The Bartered Bride: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bartered_Bride

- The Brandenburgers: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Brandenburgers_in_Bohemia

- Bedrich Smetana: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bed%C5%99ich_Smetana